Equity In Art

Poet Speaks To Current Climate

Editor’s note: Recognizing artists of color face barriers in the art world, the Equity In Art series seeks to amplify the work of minority artists. Through this series, ideastream will profile artists of various genres living and working in Northeast Ohio. Look for a new profile each Wednesday in September at arts.ideastream.org.

Born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama, Dionne D. Hunter performs under the stage name Poetess REDD, which stands for Redefining Elegance Determination and Desire.

In her adopted home of Cleveland, Hunter works as a legal assistant.

However, she said her “life blood” comes from the poems she writes and performs in the Northeast Ohio spoken word community.

Her experiences as an African-American woman living in the United States greatly influence her most recent poetry.

Dionne D. Hunter performs at Winners Luxury Lounge in Cleveland in 2013. [Jan Pezzo]

Dionne D. Hunter performs at Winners Luxury Lounge in Cleveland in 2013. [Jan Pezzo]

Dionne D. Hunter performs at Karma Cafe in Canton, Ohio in 2014. [Jan Pezzo]

Dionne D. Hunter performs at Karma Cafe in Canton, Ohio in 2014. [Jan Pezzo]

Dionne D. Hunter performs in front of the "Our Lives Matter" mural in Cleveland. [Stephon J. Davis]

Dionne D. Hunter performs in front of the "Our Lives Matter" mural in Cleveland. [Stephon J. Davis]

Dad's Dictionary

"What did you learn today?"

Hunter’s mother died when she was seven years old. Her father raised her and her siblings with a passion for the written word.

“He wanted us to stay busy in the house and stay out of trouble. So we had to read the dictionary. That sounds cliché, but when he would come home he would ask us, ‘What did you learn today?’ And we had to give him a report about what we did or learned,” Hunter said.

Soon young Dionne was putting her vocabulary to use as a child entrepreneur.

“I would knock on my neighbors’ doors and let them see the poetry that I had written or the stories I had written and ask them if they wanted something special for a birthday or an anniversary. I would write it out, draw pictures to match and then put it on the inside of folders and take it back to them. They would give me a dollar or two,” she said.

Hunter’s teachers also provided encouragement, particularly her science teacher.

“Mrs. Skelton would stay after school and read my stories and correct the papers and, you know, tell me how great I was. She really got me into science fairs. And not just me but a lot of the kids. She would take us around the city to different science fairs. If I could reach out to her, which I've tried to do and haven't been able to find her, I would let her know that she made a big difference in my life,” she said.

"Momma May I"

by Dionne D. Hunter

Momma May I look into your eyes once more

See your beautiful smile

Feel your warm embrace

Hear you calling out to me

“Come here baby let Momma kiss it, and make it feel better.”

And Yes your kisses always took the pain away

Momma, help me to erase the image of you laying lifeless, no twinkle in your eyes

You see being only a child I could not comprehend that you were never coming home to me again

I looked into your final resting place wondering why you would not wake from your deep slumber

Of course, the family tried to explain by saying,

She's gone to see God’s grace

She's going to take her honored place

God needed another angel by his side

After a while I couldn’t take anymore and I screamed, I need my Momma more than God!

But in reality my lips never parted and no one heard my inner cries

So, I decided not to worry, I told myself it was all just a bad dream

I'ma wake up, you just wait and see!

And when I wake up, Momma, she'll be standing here right by my side

But to my surprise days turned to weeks

Weeks to years and from this nightmare I never could escape

The ability to share graduation, promotions, marriage, the birth of my children, even the simple act of saying happy Mother's Day were all stolen away on that fateful day

Flash back to a silly child's pitiful cries-

Momma please open your eyes

Momma please don’t leave

Momma if you ever love me please don’t let this be goodbye

Snow Day

“We go to work in the snow up here.”

After graduating from high school in 1988, Hunter joined the United States Navy where she met her future husband from Akron, Ohio. As fiancées they moved to Ohio to marry and start a family. She remembers her first Northeast Ohio winter. One snowy morning she woke up to about a foot of snow on the ground and laid back down in bed. Her husband gave her an odd look, as he got dressed for work.

“[He] asked me what I was doing. I said, ‘Going back to sleep, nobody can get around in all that snow.’ He looked me in the eye and said, ‘We go to work in the snow up here.’ I laughed and told him that he was crazy but he persisted, so I eventually got ready for work. I fussed the entire way, and I was astounded as he drove me into my employer’s parking lot. It was full! He pulled in front of the building and just laughed and laughed as I reluctantly pulled myself out of the car. You have to remember in Birmingham if you get a handful of snow the entire city is closing down. So I was pretty dumbfounded,” she said.

Despite the cold winters of Northeast Ohio, Hunter would later discover a warm reception from the spoken word communities of Cleveland, Akron and Canton.

Dionne D. Hunter's U.S. Navy basic training graduation photo, 1989

Dionne D. Hunter's U.S. Navy basic training graduation photo, 1989

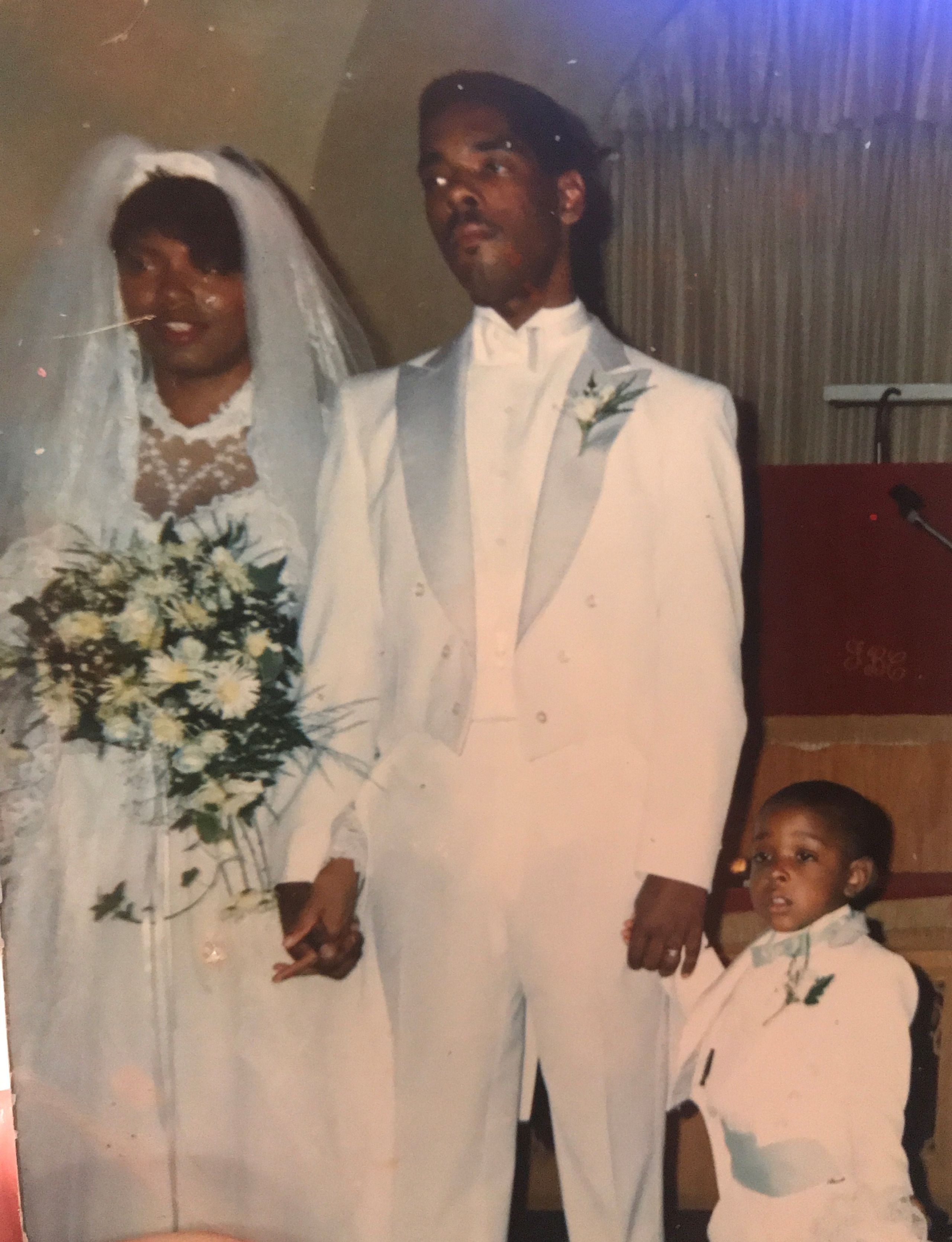

Dionne D. Hunter and Marshall Turner wedding photo, 1990, with Stephon Turner

Dionne D. Hunter and Marshall Turner wedding photo, 1990, with Stephon Turner

Poetic Support

“The energy in the air and the light in peoples’ eyes”

Hunter has written throughout her life but until eight years ago she’d never thought about performing her poems in front of an audience. That changed when she experienced her first spoken word performance.

“[I] saw just the energy in the air and the light in people's eyes, and I said, 'Hey, I wonder if I could do something like that to get my point across and not just writing, but also emotionally speaking,’” she said.

She decided to give it a try in 2012. The first spoken word poem Hunter ever performed in public was dedicated to her late mother, “Momma May I,” at the former XL Lounge in Cleveland’s Gateway District.

“That night, I couldn't even make it through the piece. I cried on stage. I didn't know if it was something that I would want to do, because it just was so emotional for me. But the spoken word community, the poetry community, the audience that was there, really held me up,” she said.

The audience connected with her story and the other poets encouraged her to come back and share more of her poetry. Soon Hunter was getting offers to perform and started to get paid for those performances.

“My first point of interest was to get across a message to people and then it was, ‘Oh, I can make a little money doing this as well? That's awesome.’”

Hunter said she’s blessed to have had mostly positive feedback about her poetry. But a recent poem struck a nerve with someone in the audience.

After recently performing her poem,“Black Lives Do Matter,” a young man approached her to say that he didn’t agree with its message and that the poem didn’t speak globally enough about all the aspects of the issue.

“I wanted to hear his point of view. That is actually the point of the piece, to start a conversation,” she said. “He took a different view, but we were able to have an open dialog, which I thought was great.”

When Hunter's two children heard the poem for the first time they went to their mom and embraced her and told her how proud they were. It was one of the best moments of Hunter's life, she said.

![Dionne D. Hunter performs [Jan Pezzo]](./assets/nUykG1CCYS/dionne-performs1-1235x1815.jpeg)

![Dionne D. Hunter performs [Jan Pezzo]](./assets/LvvwlvNtnz/dionne-performs7-960x640.jpeg)

![Dionne D. Hunter performs [Stephon J. Davis]](./assets/IPAxyGOKMc/dionnemural1-2208x1242.jpeg)

Black Lives Do Matter

“There can be so many ways you can be strangled”

Hunter’s “Black Lives Do Matter” poem is the result of many years of racist experiences as an African-American woman.

Her widowed father worked at the post office and at times the family lived paycheck to paycheck. In high school, Hunter took a commercial art class, but she needed to wait a few days before buying her art supplies. So she asked a fellow student, who was white, to borrow some of his colored pencils.

“And he asked me, ‘Why don’t you have your stuff? Haven't gotten your welfare check yet?’ And I honestly, and I'm not being facetious, I didn't even know what a welfare check was because my dad worked every day,” she said. “We weren't on the system and I didn't know anything about it. But [that student] and other people in the class had a generalized view of Black people that they're all using food stamps or getting some type of check from the government,” she said.

Hunter’s father raised her and her siblings to honor the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., however in the 1980s Martin Luther King Jr. Day was not a holiday in Alabama. One year, Hunter and her African-American classmates decided to protest by staying home from school that day.

“The next day in class, the white kids, some of them, a majority of them were like, ‘School was better without you guys. You need to stay gone more often,’” she said.

Hunter supports the Black Lives Matter movement and is frustrated by misconceptions about it.

“When you say, ‘Hey, today is my birthday.’ Nobody comes over to you and says, ‘yeah, but it’s 500 other peoples’ birthday in Cleveland as well.’ We're saying Black Lives Matter for a particular reason. And that's because for so long they did not matter,” she said.

Another of Hunter’s works influenced by the Black Lives Matter movement is the poem “I Can’t Breathe.”

“There can be so many different ways you can be strangled. You can be strangled because of brutality where someone is putting their knee on your neck and you can't breathe and you pass away. And there's also a strangulation of faith or spirit where you can't rise above what is going on in your specific circumstance,” she said.

This poem has specific resonance for Hunter as it harks back to a dark memory from her youth.

In 1984, Hunter’s Uncle Kenny was stopped for a traffic violation in Birmingham. He called her father and asked him to pick him up. In the time that it took her father to get dressed and drive to the police department, the police said that they found her uncle in his cell, dead, she said.

“And of course, you know, back in 1984, there weren't cellphone cameras or, you know, when the police said something that's basically what it was,” she said.

Hunter said she wonders how a young, vibrant man like her uncle could die while waiting for a ride home.

“Brutality just didn't start happening today. It's been happening for a long time. It's just caught on camera now,” she said.

Hunter doesn’t condemn all police officers.

“I know many people who are police officers, and in no way do I think that all police officers are bad,” she said. “Just because a whole group isn't bad doesn't mean that there needs to be no more regulation.”

Racist behavior today is more anonymous, Hunter said. She experienced this once at a bar in Twinsburg when she heard someone openly direct a racial slur at her and her African-American friends.

“Of course, it was in a crowd, so you couldn’t tell who said it. And a lot of times now that’s how discrimination shows it’s ugly face,” she said.

Dionne D. Hunter performs "Black Lives Do Matter." [Stephon J. Davis]

Dionne D. Hunter performs "Black Lives Do Matter." [Stephon J. Davis]

Onward

“There has to be a way to enlighten people.”

Hunter’s children Marshall and Leah were born in Akron and now are grown. After divorcing her husband, who since passed away, Hunter moved from Akron to Cleveland to be closer to her day job.

After the move, Hunter went on to compete in and win the annual Hessler Street Fair Poetry Contest, a longstanding Cleveland event. Her poems were published in subsequent contest anthologies.

She’s currently recording her latest poems as an EP and “mini-visual” album in hopes of releasing them in early 2021.

One of those most recent poems, “Onward,” looks to a little known piece of African-American history from the 19th century – The Freedman’s Bank. Established by the U.S. Congress in 1865 to help recently emancipated African-Americans, the bank collapsed less than a decade later taking millions of invested dollars with it.

“If you think about it, how many families would be in different situations today if that money was available to them, as it should be?” she said.

Through her poetry Hunter said she hopes to provide information like this to others who might be exhausted and turned off by news coverage of current events.

“You see things going on in society and you want to get people excited about it or give them knowledge,” she said. “There has to be a way to enlighten people, you know, other than the norm.”

Hunter likes to write romantic poetry as well and doesn’t consider herself “super political.”

“But when you live in this skin that I’m in, it causes you to be more aware of the injustices going on around you because you’re living with and through it,” she said. “My ultimate goal is to leave this world knowing that I did my best to improve circumstances for my children and grandchildren.”

![Dionne D. Hunter [Bryant Reynolds]](./assets/MLDAd3lkDQ/dionneblm-mural3-678x960.jpeg)

![The Freedman's Bank [Public Domain]](./assets/9ptsOF1rXk/freedman-s_savings_bank-470x488.jpeg)