Equity In Art

Balancing Biracial Identity

Editor’s note: Recognizing artists of color face barriers in the art world, the Equity In Art series seeks to amplify their work. Through this series, ideastream profiles artists of various genres living and working in Northeast Ohio. Look for a new profile each Wednesday in April and find past profiles at arts.ideastream.org

This story also includes imagery showing racial violence.

!["Beams," 2015 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/TdWeXwKKB4/beams-1000x667.jpeg)

Omid Tavakoli loves to garden, whether it’s echinacea or zinnia flowers or vegetables like tomatoes, lettuce and zucchini.

He's even spent time reviving a sculpture garden near where he grew up in Euclid.

As a child, Tavakoli was raised in an apartment with a balcony instead of a back yard. Now, given the opportunity to have his own yard with a garden, he digs in each spring.

Back in 2011, however, Tavakoli was transfixed by a different kind of spring — the Arab Spring, a series of political protests in countries such as Libya, Egypt and Tunisia.

!["PrÆy and Azar" are silk banners featuring images of women wearing hijabs. 2019 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/IdYKUIlddV/detail-praey-and-azar-2019-42-x-15-dye-sublimation-print-on-silk-2560x1707.jpeg)

"PrÆy and Azar" are silk banners featuring images of women wearing hijabs, 2019 [Omid Tavakoli]

"PrÆy and Azar" are silk banners featuring images of women wearing hijabs, 2019 [Omid Tavakoli]

Last year, almost a decade later, Tavakoli was inspired by the Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd.

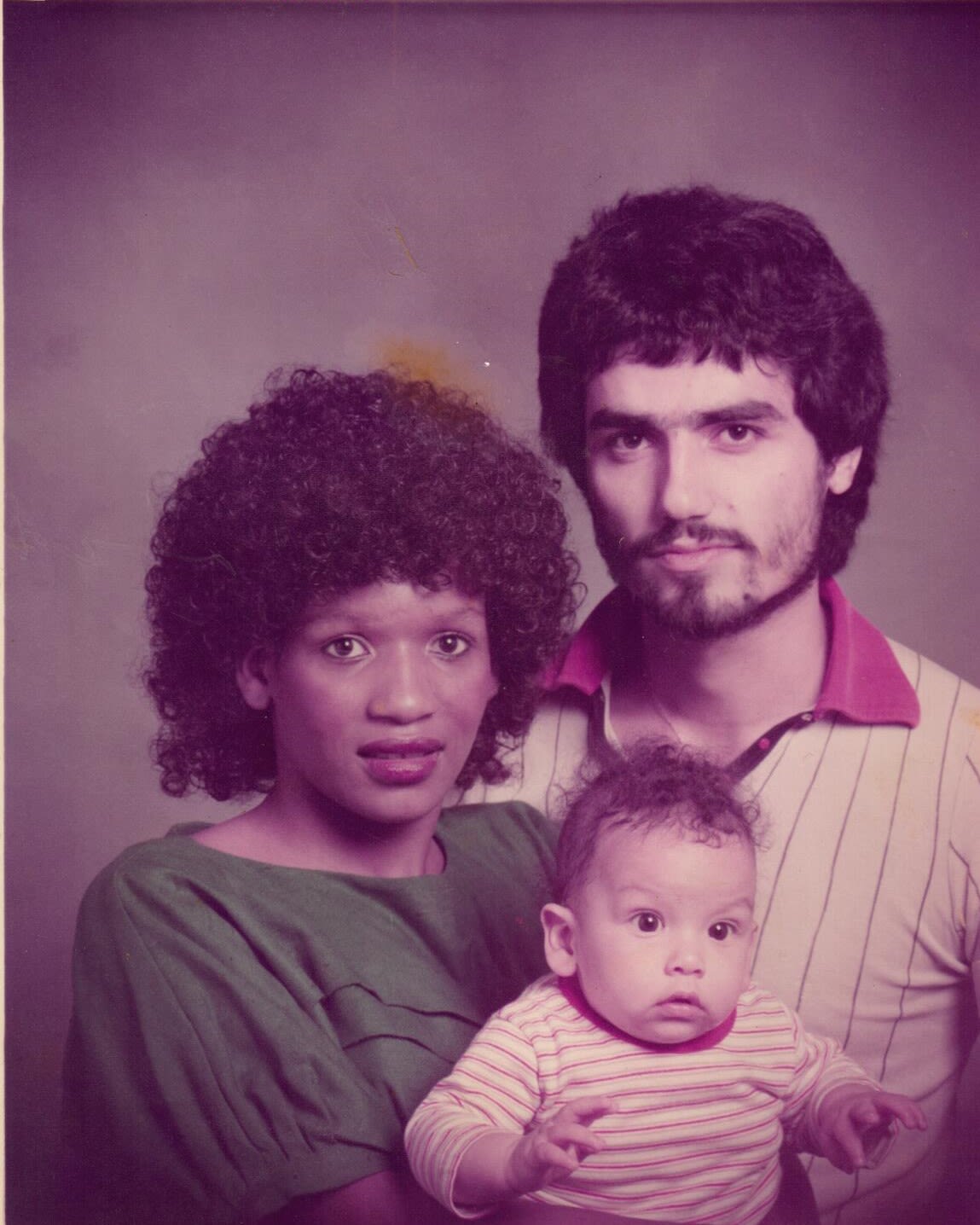

He sees connections between these international outcries in part due to his family’s heritage – his mother is African American while his father was born and raised in Iran.

!["Over Policing (Transparency)," 2020 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/TkG6BMRE1X/2overpolicing20x10print-2560x1280.jpeg)

"Transparency," 2020, is part of his "Over Policing" series. [Omid Tavakoli]

"Transparency," 2020, is part of his "Over Policing" series. [Omid Tavakoli]

This dual identity springs out of Tavakoli’s art, which is at once shocking and informative yet beautiful.

Omid Tavakoli with his plants [Breanna Kulkin]

Omid Tavakoli with his plants [Breanna Kulkin]

Arab Spring protest in Yemen, 2011 [ympphotos / Shutterstock.com]

Arab Spring protest in Yemen, 2011 [ympphotos / Shutterstock.com]

Black Lives Matter protest in Miami, 2020 [Tverdokhlib / Shutterstock.com]

Black Lives Matter protest in Miami, 2020 [Tverdokhlib / Shutterstock.com]

Coloring With Mom

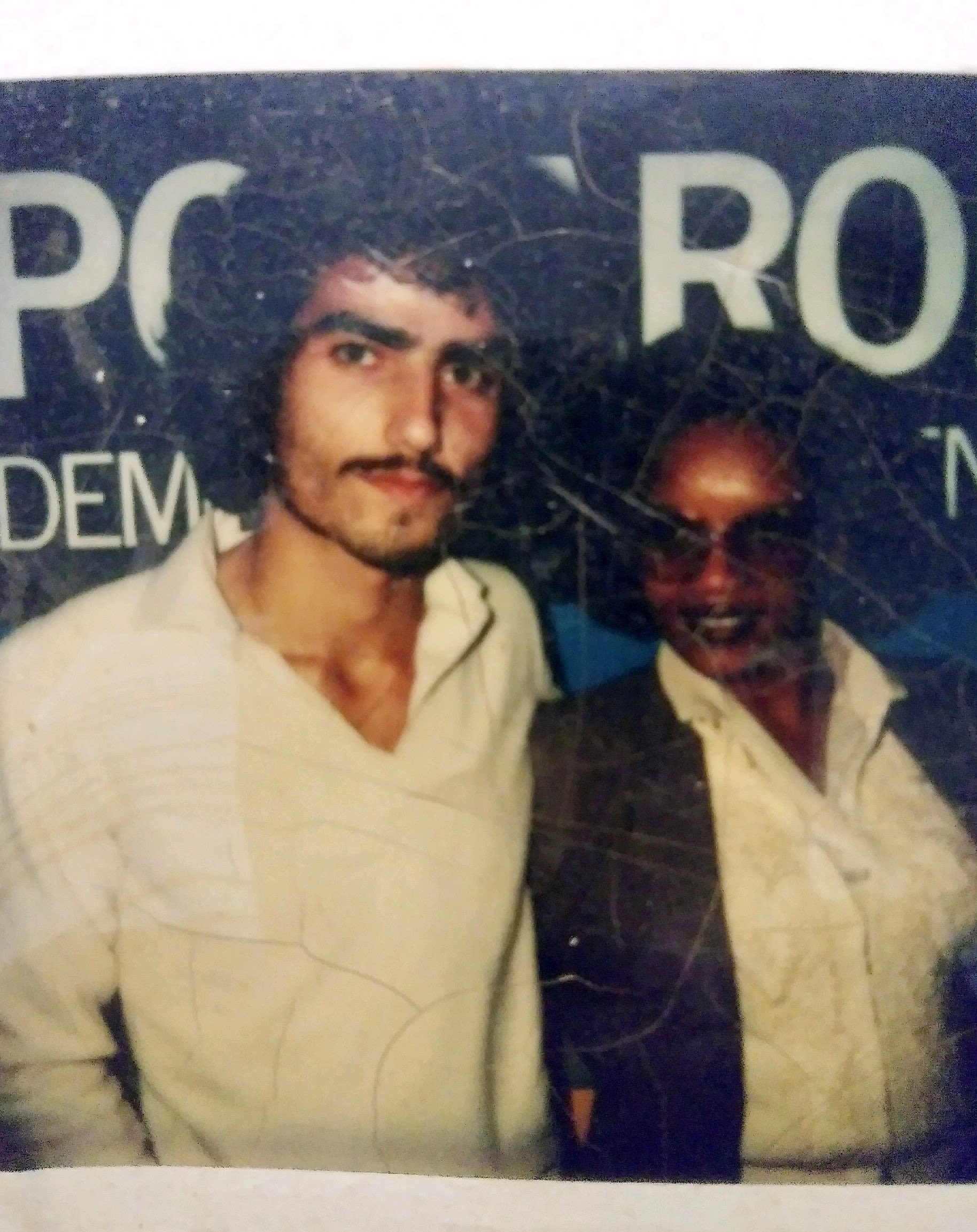

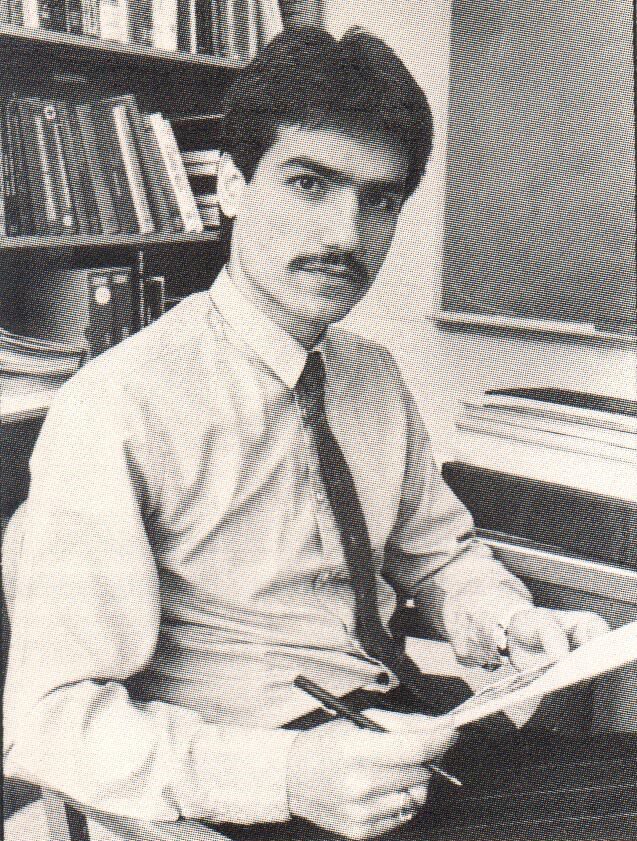

Tavakoli’s earliest memories of enjoying art involve his parents, Amir and Inez. The two met in Georgia but moved to Euclid after Amir landed a job at Case Western Reserve University as an assistant professor of engineering when Omid was five.

Cleveland’s University Circle soon became a favorite family destination as they’d drive through the circle together taking his dad to CWRU.

“I attribute that ride through the cultural gardens and those moments at the [Cleveland Museum of Art] or the moments at the pond or little things. I'm literally six years old at this time. I think that really rubbed off on me,” he said.

He also has fond memories of finger painting in kindergarten.

“They would have you take your dad's work shirt, one of those collared white shirts, and then have you wear it inside out. It was like your art apron, which is really interesting. It made you feel like it was official,” he said.

Meanwhile his mother introduced him to coloring books.

“My mom would color with me and hers would be magnificent, everything's inside the lines. [Her] coloring was beautiful and mine would just be horrendous,” Tavakoli said.

For a time, he soured on art because he couldn’t draw very well. But when he got to Euclid High School a funny thing happened. His art teacher recognized him.

“It was this kind of cool moment where she's like, ‘Oh, you're Omid.’ And I'm like, ‘Yeah.’ And she's like, ‘You were my student in kindergarten,’” he said.

While this chance reunion with an art teacher left a big impression on Tavakoli, it wasn’t enough to get him over the fact that his parents had previously separated, leaving him disillusioned and depressed. He developed a reputation around school as a slacker.

Omid's parents Amir Tavakoli and Inez Jones [Omid Tavakoli]

Omid's parents Amir Tavakoli and Inez Jones [Omid Tavakoli]

Amir Tavakoli [Omid Tavakoli]

Amir Tavakoli [Omid Tavakoli]

Inez, Amir and Omid Tavakoli [Omid Tavakoli]

Inez, Amir and Omid Tavakoli [Omid Tavakoli]

'You’re Not Going To College'

![Self portrait 2015 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/hbTM0bkogr/cia-self-portrait-711x711.jpeg)

As graduation approached and with college on the horizon, Tavakoli went to see his high school guidance counselor.

“He just looked at my grades, which were struggling at the time. I had issues at home and some other personal things that were happening,” Tavakoli said. “He looked at me and was like, ‘You're not going to college, right?’ I still don't know if it was a race thing, or if it was just the grades... But at that point, I just said, ‘No.’”

As he watched his friends apply to major universities, he started thinking about attending community college.

“I think it would have been nice if that counselor had just pointed me in some other directions,” he said.

Immediately after graduation, Tavakoli began receiving frequent calls from the United States Army trying to recruit him.

“I remember asking all of my white friends at the time, ‘Hey, are you getting these calls?’ and they’re like, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’” he said.

Tavakoli made his way to Cleveland State University but dropped out to help care for his mother who was having major health issues. She died of kidney failure in 2007.

The death of his mother spurred Tavakoli to return to CSU. He switched his major to art history.

![Self portrait [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/CgpM0HswWY/cia-silver-print-portrait-960x960.jpeg)

Two Identities

His first two art history classes were African American art and Islamic art, which began Tavakoli’s deep artistic dive into his own heritage.

“I've got these two identities. As a biracial kid, you always have your own identity issues and you're either embracing them both or rejecting them both,” he said.

After 9/11, discrimination against Muslims led Tavakoli to hide his Iranian background. But in 2009, he couldn’t ignore what became known as the “Persian Spring,” when Iranians took to the streets to protest the presidential election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad [stocklight / Shutterstock.com]

Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad [stocklight / Shutterstock.com]

“I've always been fascinated by Iran… it was an influential moment, to say the least. There was something happening,” he said.

Iran elections protest in Canada, 2009 [Paul McKinnon / Shutterstock.com]

Iran elections protest in Canada, 2009 [Paul McKinnon / Shutterstock.com]

Twenty-six-year-old Iranian musician Neda Agha-Soltan was shot and killed during the protests, making international headlines and instilling pride and sadness in Tavakoli for his father’s homeland. He was astonished when the death of pop star Michael Jackson five days later erased her name from the news cycle.

!["The Girl of Enghelab Street," 2018 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/lqrxTpBc90/girl-on-englahab-2560x3840.jpeg)

"The Girl of Enghelab Street," 2018 [Omid Tavakoli]

"The Girl of Enghelab Street," 2018 [Omid Tavakoli]

A year later, similar protests occurred in Middle East countries like Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Syria. It became known as the Arab Spring. These protests would serve as inspiration to Tavakoli once he began his MFA at Kent State University in 2017.

!["PrÆy and Azar" [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/efcOpzuesv/img_2204-2560x1920.jpeg)

![Arab Spring protest Yemen 2019 [ymphotos / Shutterstock.com]](./assets/JQKm0ZpHSR/arbspring2_ymphotosss-2560x1703.jpeg)

![Neda Agha-Soltan memorial [360b / Shutterstock.com]](./assets/puc25acKKE/neda_360b-2560x1707.jpeg)

A Carton Of Eggs

!["The Price of Eggs and Bread" 2018 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/g3crV8CBya/tavakoli3-2560x1707.jpeg)

As a graduate student, Tavakoli started exploring his identity through art beginning with his Middle Eastern roots.

He was fascinated by Iranians of his generation who were out in the streets protesting. This led him to research Iran’s recent history going back to the 1979 Revolution.

Tavakoli learned that many of Iran’s political protests started over food prices for everyday items like bread and eggs, which gave him an idea.

“I would take carton after carton of eggs… I would get like a whole square of eggs. Twenty four eggs in a square and lay that down and then put a piece of lavash, which is Iranian bread or Persian Middle Eastern bread, on top of that,” he said.

He created a tower of eggs and bread standing four feet high that quickly collapsed in the school’s gallery, crushing many of the raw eggs on the floor in what he describes as an, “amazingly beautiful way.”

“This piece ended up getting a lot of attention within the school. I think more the shock, the smell, the sulfur, the eggs… I had teachers who really didn't know who I was, kind of knowing who I was from that point,” he said.

Tavakoli in turn started to know and understand how his Iranian American and African American heritage would influence his art going forward.

!["Ashes Under the Rug," 2019 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/tbjZ8CVTze/ashes-under-the-rug-2560x1920.jpeg)

"Ashes Under the Rug," 2019 [Omid Tavakoli]

"Ashes Under the Rug," 2019 [Omid Tavakoli]

These works would lead to Tavakoli’s KSU graduate thesis, “A Burning Silence.”

Lean Into It

![Detail of large-scale work, "Save Our Saints, Take a Knee for Alton Sterling," a collage depicting NFL players digitally edited alongside Black victims of police brutality [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/cC1pR8uppM/alton-stering_150-ppi-1500x1008.jpeg)

When asked if he considers himself an artist of color Tavakoli brings up the late African American portrait painter Barkley L. Hendricks.

“I read something of [his] that said something like, ‘just being Black and making art is political.’ That’s just a fact so you might as well lean into it,” Tavakoli said.

He began exploring his African American roots by creating a series about protests in the NFL.

Growing up a football fan, Tavakoli was inspired by players like Colin Kaepernick, known for taking a knee during the national anthem to protest racial injustice in America.

Tavakoli’s “Take a Knee" series is a collection of collages where the protesting players are digitally edited alongside the Black victims of police brutality who inspired their protests.

“Really, each city, each sports team, probably has one person in that city that's been murdered by the police… So I was able to take a person like Eric Garner, who was killed in New York, and actually take the team, both NFL teams that are protesting these deaths and put them on the same field together, really show that, like the Jets, the Giants and this gentle giant, Eric Garner, can all be on the same field,” he said.

He continued the series with Freddie Gray and the Baltimore Ravens, and Alton Sterling and the New Orleans Saints. Tavakoli says someday he may create a work about the death of Cleveland’s Tamir Rice but admits the ongoing series has taken a toll on his psyche.

“These works take hours. You're layering… you're physically looking at a dead child for hours… I think I kind of started to pull away from that work,” he said. “There has to be a way to tell these stories without being so shocking or without putting that additional stress on myself.”

Respect The Water

!["Sea of Cops" is part of the "Over Policing" series. 2020 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/IGXsCPfDet/field-of-cops-2-2000x2000.jpeg)

In the spring of 2020, George Floyd’s death and the ensuing Black Lives Matter protests across the nation sparked a new creative fire in Tavakoli.

George Floyd protest in Cleveland, 2020 [Jenny Hamel / ideastream]

George Floyd protest in Cleveland, 2020 [Jenny Hamel / ideastream]

However, because his asthma makes him a high risk for COVID-19, Tavakoli did not feel safe joining the protests on the city streets.

“So, it's like, ‘How do I make something or an answer, add something to this conversation?’” Tavakoli said.

He began manipulating news images of the protests and specifically images of police. These new works evolved into the series "Over Policing." Because of their immediacy, rather than waiting for a gallery show, Tavakoli posted the pieces right to Instagram.

!["Excessive Farce," 2020 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/2u0Xl6MXb5/excessive-farce-print-11x14-2560x3258.jpeg)

"Excessive Farce," 2020 [Omid Tavakoli]

"Excessive Farce," 2020 [Omid Tavakoli]

“I wanted to be quick and out there if I saw something happening in the news that was responding to it that day. I got forced to make some things quickly,” he said.

The metaphor of a large body of water added another emotional layer of meaning to a set of pieces called "Sea of Cops."

Omid Tavakoli at Lake Erie shore [Omid Tavakoli]

Omid Tavakoli at Lake Erie shore [Omid Tavakoli]

“I'm from Euclid. We see the lake, we see water, you know, the turbulence… And I start seeing these relationships with the police. It's like they always tell you: Respect the water. The water's dangerous. The water can capture you at any time. You can drown, you can get swept in a tide… But as a young Black male, you're always told: Respect the police. Be careful, watch out,” he said.

While “Sea of Cops” is striking and disturbing, there’s an additional element of ironic beauty.

“I'm always wondering, ‘Can you sell something that's disturbing or can you sell something that doesn't have that layer of beauty?’” Tavakoli said. “It's something I'm navigating, but I was definitely conscious of, ‘How can I make this look interesting?’… There's always the horizon line. The horizon line is such a significant thing for the lake and water and the beauty of [it].”

Tavakoli displayed his "Over Policing" series at Heights Arts gallery in early 2021. One of the “Sea of Cops” works was Tavakoli’s first piece to sell from that exhibition.

![Deep Dark Sea of Cops, 2021 [Omid Tavakoli]](./assets/6KULDRWbTK/deep-dark-sea-of-cops1-2560x1218.jpeg)

"Deep Dark Sea of Cops," 2021 [Omid Tavakoli]

"Deep Dark Sea of Cops," 2021 [Omid Tavakoli]

House Full Of Seeds

![Omid Tavakoli [Breanna Kulkin]](./assets/iAvW1NAqtt/watering-plants-2-640x427.jpeg)

Omid Tavakoli [Breanna Kulkin]

Omid Tavakoli [Breanna Kulkin]

Omid Tavakoli working in the Waterloo Sculpture Garden. [Omid Tavakoli]

Omid Tavakoli working in the Waterloo Sculpture Garden. [Omid Tavakoli]

Omid Tavakoli working in the Waterloo Sculpture Garden. [Omid Tavakoli]

Omid Tavakoli working in the Waterloo Sculpture Garden. [Omid Tavakoli]

Omid Tavakoli

Omid Tavakoli

With the gallery show closed, Tavakoli is hard at work on his next project: his garden.

“I grew up in an apartment building. We had no garden and I had a balcony for the longest time. So, I feel like I've always wanted to garden,” he said. "I would go to my grandmother's house because she had a house [in Pittsburgh], and I'd plant stuff in her yard… surprise her on Mother's Day and put tomatoes in,” he said. “That carried over [when] my mom was alive. She had her home, and I would do the same thing.”

The fact that his mother passed before his career as an artist began leaves a hole.

Omid Tavakoli with his late mother, Inez. [Omid Tavakoli]

Omid Tavakoli with his late mother, Inez. [Omid Tavakoli]

“I wish she had seen me make art,” he said.

While at CSU, Tavakoli worked at Waterloo Arts in Cleveland’s Collinwood district and put his planting skills to use in a community sculpture garden.

“I wasn't doing sculpture, but I felt like I knew enough sculptors to talk to some people. I talked a couple of friends into bringing some of their work out or making something for the space,” he said.

Tavakoli has always felt rejuvenated by the spring season.

“In Iran our New Year's is actually the first day of spring. So, there's something really invigorating about this time of the season. Like right now, my house is full of seeds. I've got 300 lettuce seeds growing right now, and I started tomatoes yesterday,” he said.

Tavakoli plans to begin his next art project soon. Surely something will sprout from his artistic soil.

Omid Tavakoli leads Earth Day event at Waterloo Sculpture Garden. [Omid Tavakoli]

Omid Tavakoli leads Earth Day event at Waterloo Sculpture Garden. [Omid Tavakoli]