Art Saves:

Daniel Gray-Kontar's

artistic rebirth after

creative crash

Editor's note: This story is part of a series exploring how art saves people’s lives. Whether someone faces mental illness, systemic social barriers or any other challenges, art in its many forms offers a way to express, heal, transform and find joy.

Major poet, major player

The long list of accomplishments by Cleveland poet and educator Daniel Gray-Kontar is remarkable.

In his early 20s, he burst onto the literary scene as a member of the history-making Cleveland Slam Poetry team, winning nationals in 1994. Returning to Cleveland a mini celebrity, Gray-Kontar co-founded the Black Poetic Society in 1997, uniting Black poets from across Northeast Ohio.

“I’m very proud of my experience with Black Poetic as a founder and as being one of the progenitors of the Black poetry movement [in Northeast Ohio],” Gray-Kontar said.

With a bachelor’s degree in English and Pan-African Literature from Cleveland State University, he headed to the University of California, Berkeley to pursue a doctorate in education. Soon after, he was recruited to redesign the Cleveland School of the Arts literary arts department in 2013.

That experience led Gray-Kontar to open his literary workshop and performance space, Twelve Literary Arts, for which he received the prestigious national Joyce Award for innovative arts programming and leadership. He ran Twelve Literary Arts until 2022.

“Twelve Literary Arts was a whirlwind,” he said. “We did so much in that period of time it really boggles my mind.”

A major player in the Cleveland arts scene, Gray-Kontar either consulted with or joined boards for Northeast Ohio arts and culture organizations such as the Cleveland Foundation, the Gund Foundation, Northeast Ohio Shores Development Corporation, the Cleveland Arts Prize and Brews & Prose.

For Gray-Kontar, it was during his six-year run at Twelve Literary Arts where he hit high marks as an arts educator, but it was also during this time that his ever-expanding role as an arts administrator landed him in the hospital.

“I was not making art at all, [for] about five or six years, maybe longer than that,” he said.

“I need to make art for my own health.”

Almost two years after closing the doors on Twelve Literary Arts, Gray-Kontar is rediscovering his passion and love for making art. He has returned to another of his enjoyed mediums - music - which gave way to a new creative outlet – AI art.

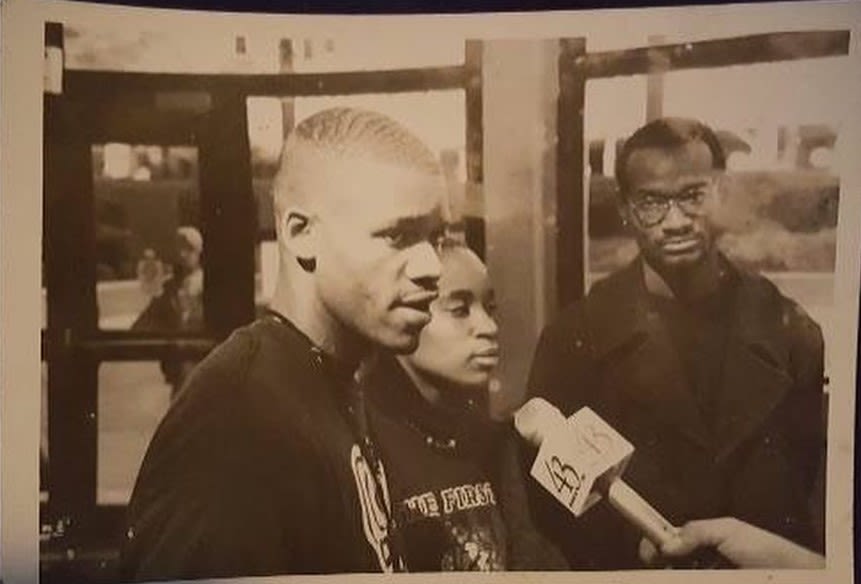

Daniel Gray-Kontar (left) with the 1994 Cleveland Slam Poetry team including poets Ray McNiece, Tia Dionne Hodge and Kwanza Brewer. [Daniel Gray-Kontar]

Daniel Gray-Kontar (left) with the 1994 Cleveland Slam Poetry team including poets Ray McNiece, Tia Dionne Hodge and Kwanza Brewer. [Daniel Gray-Kontar]

Daniel Gray-Kontar (right) with members of the Black Poetic Society. [Black Poetic Society]

Daniel Gray-Kontar (right) with members of the Black Poetic Society. [Black Poetic Society]

Daniel Gray-Kontar (top center) with students from Twelve Literary Arts. [Stephen Bivens]

Daniel Gray-Kontar (top center) with students from Twelve Literary Arts. [Stephen Bivens]

Daniel Gray-Kontar interviewing playwright Dominique Morrisseau at the City Club of Cleveland [Michaelangelo's Photography]

Daniel Gray-Kontar interviewing playwright Dominique Morrisseau at the City Club of Cleveland [Michaelangelo's Photography]

Artistic intelligence

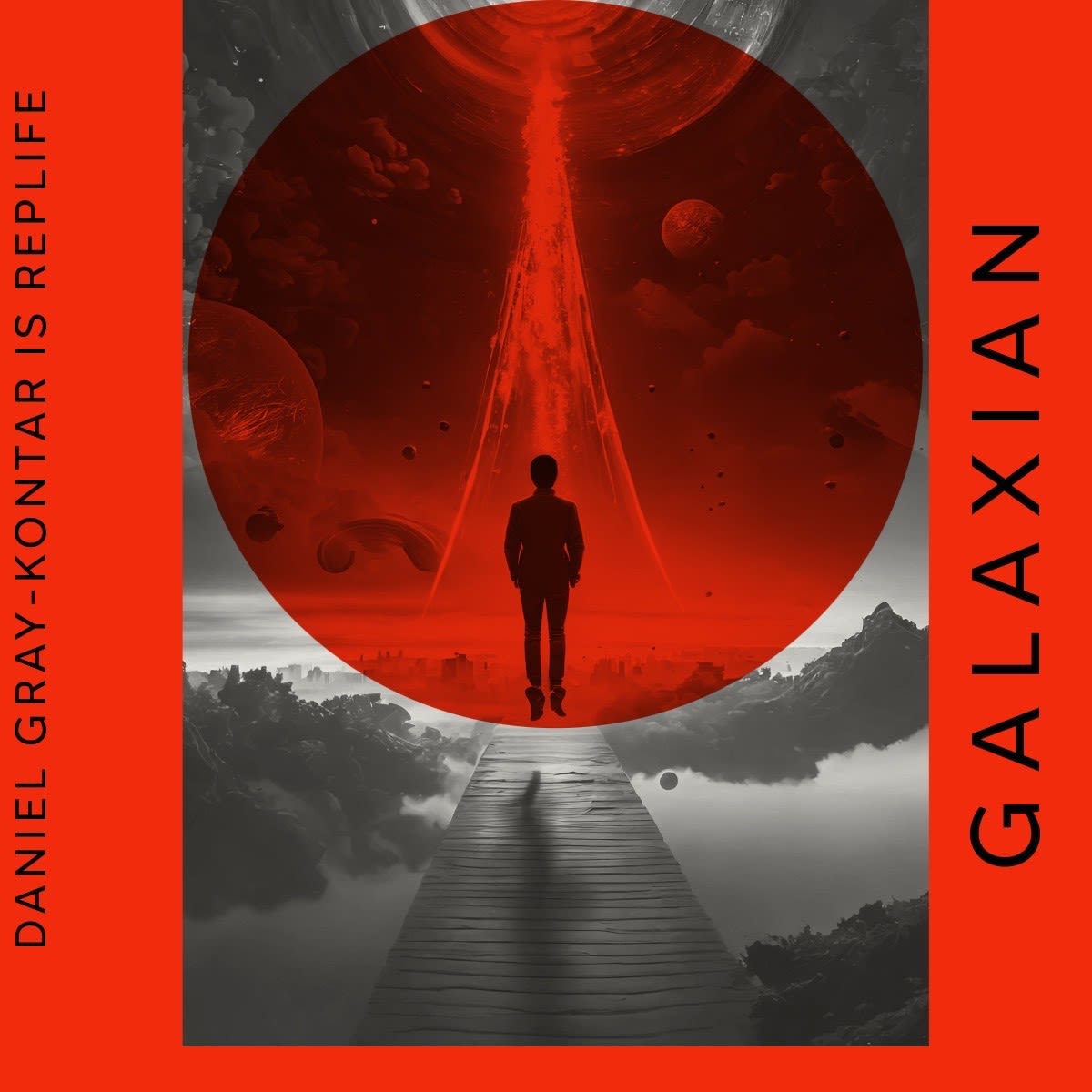

Back in February, while recording a new album as his musical alter-ego Replife, Gray-Kontar decided to save some money by creating the album cover himself.

“I never considered myself a visual artist at all, although I’ve always had a great appreciation for it,” Gray-Kontar said.

As he began working with artificial intelligence to make his album art, Gray-Kontar fell down a rabbit hole.

“The next thing you know, I’m sitting, creating, spending like five, six, seven hours working on this one piece,” he said.

“The joy I experienced, that I started experiencing creating this stuff …I hadn’t felt anything like it before.”

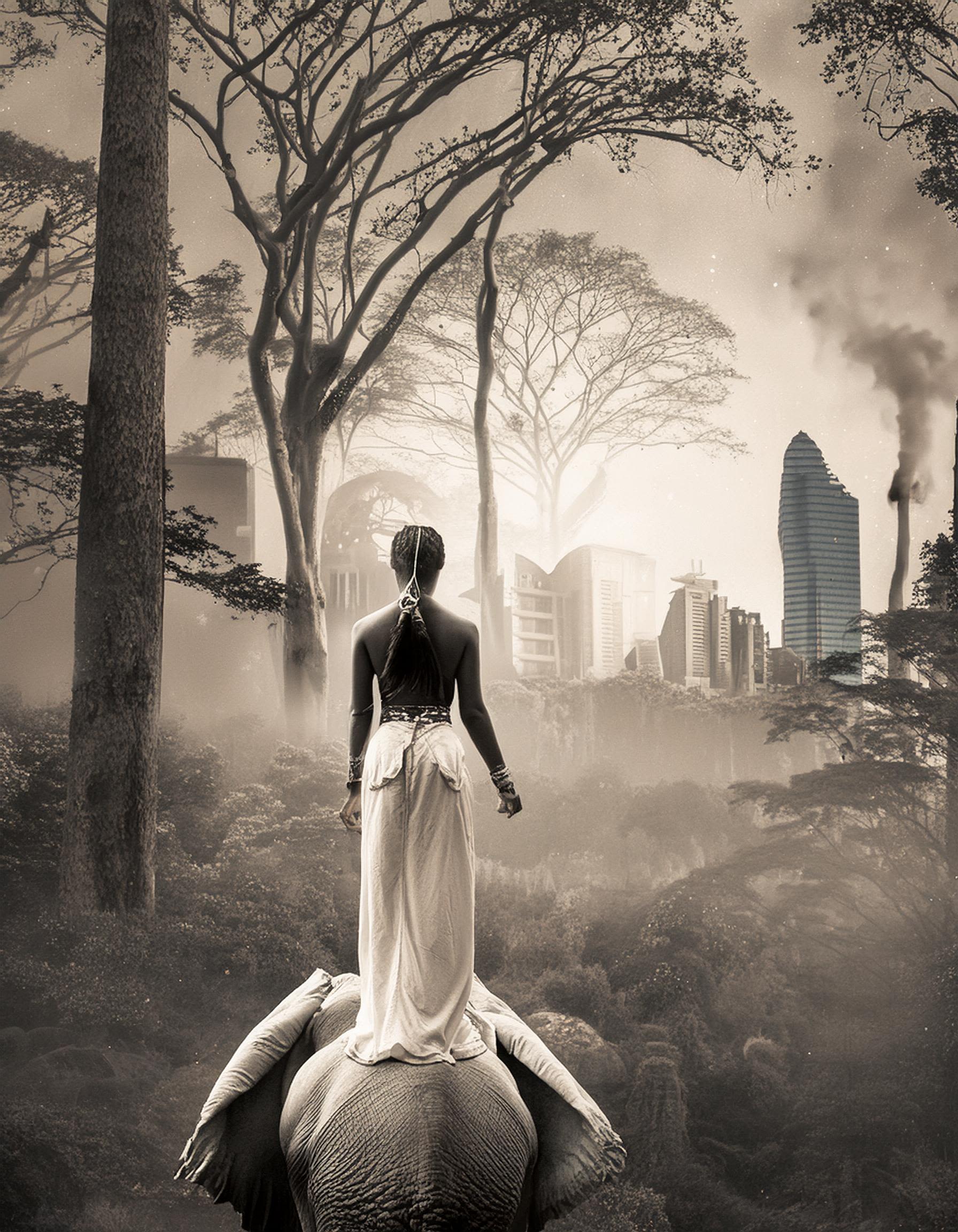

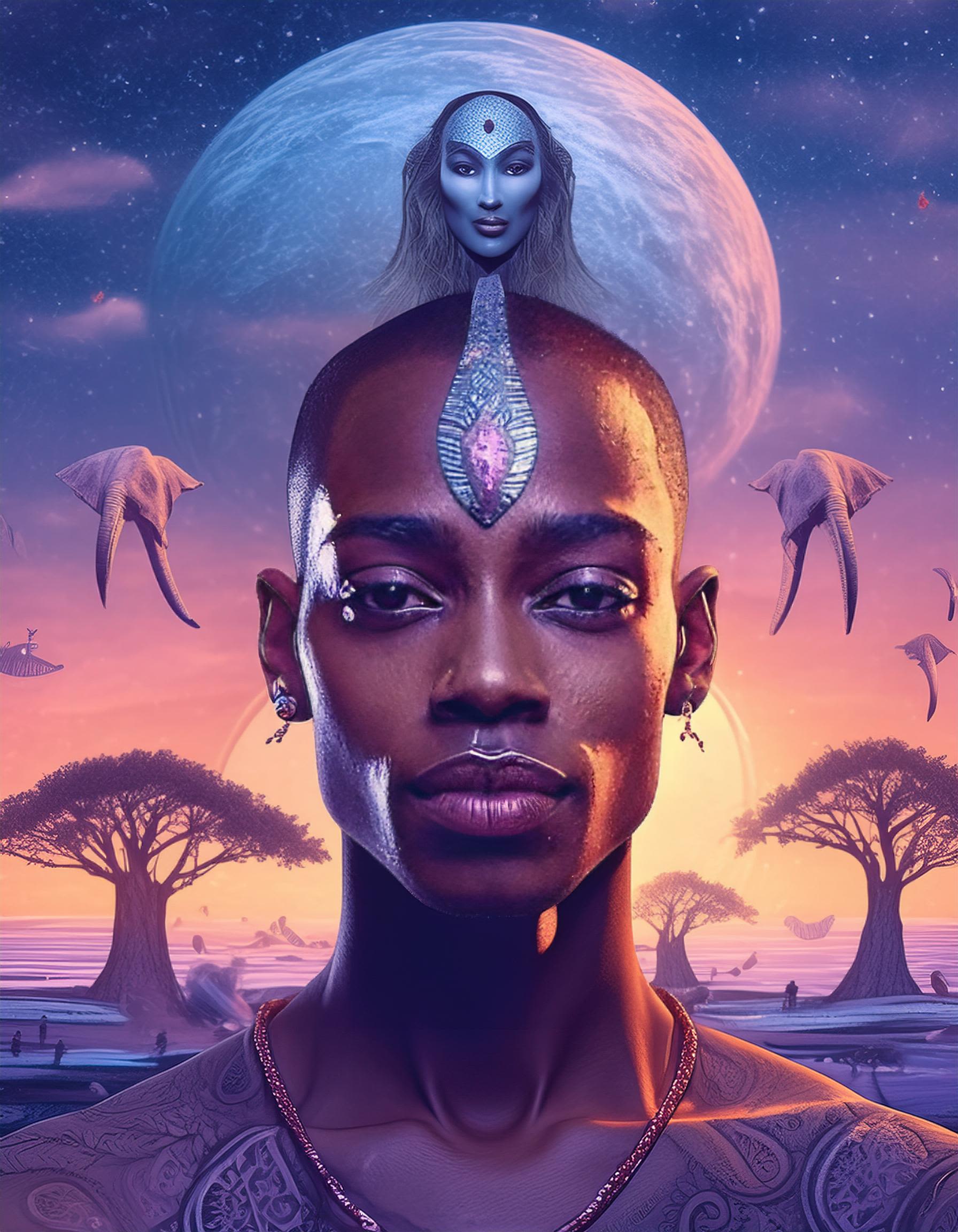

Gray-Kontar began sharing his AI creations of Afrofuturist imagery on his social media accounts and an overwhelming positive response spurred him to do more.

After years of letting his role as an arts administrator consume him, Gray-Kontar was making art again.

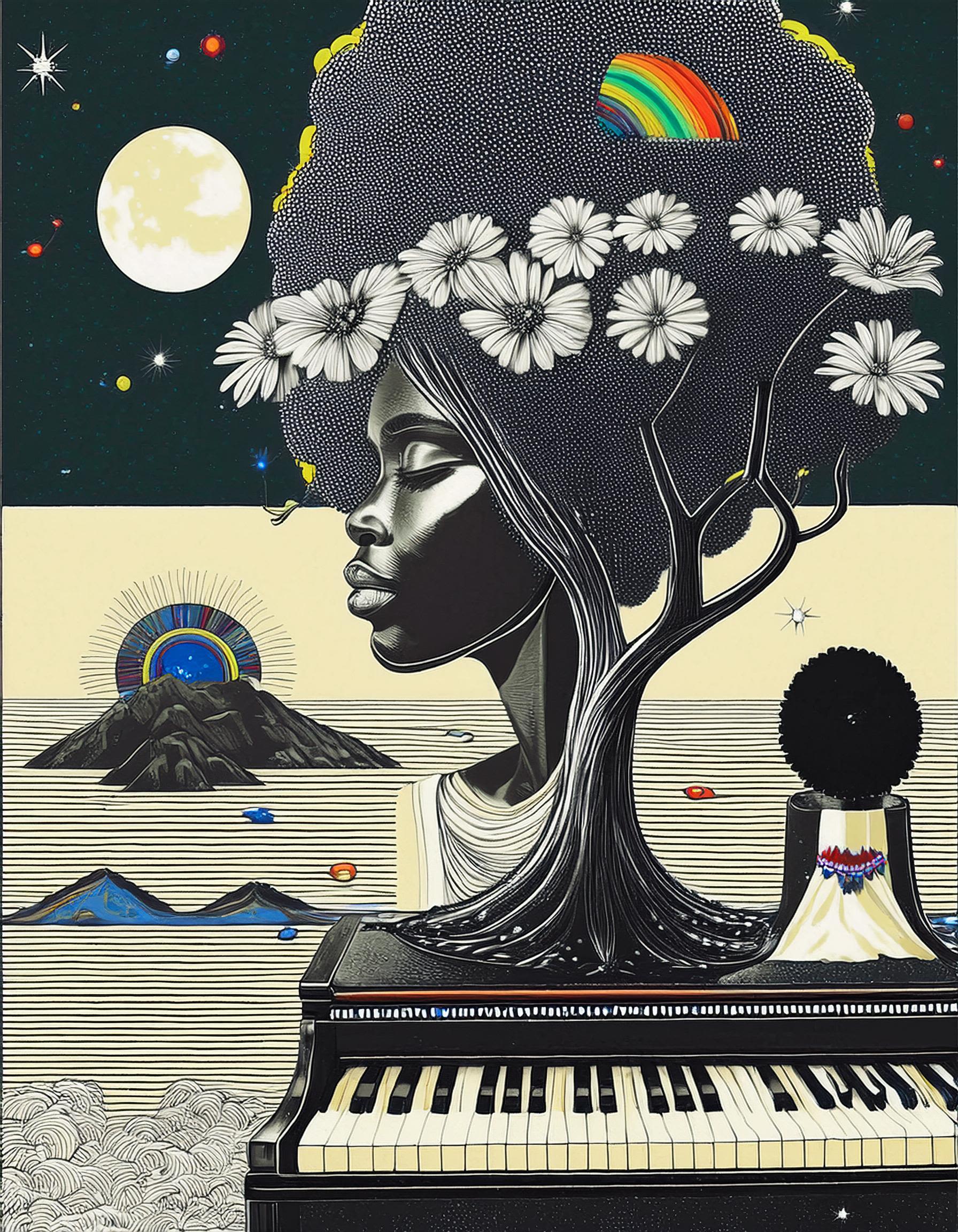

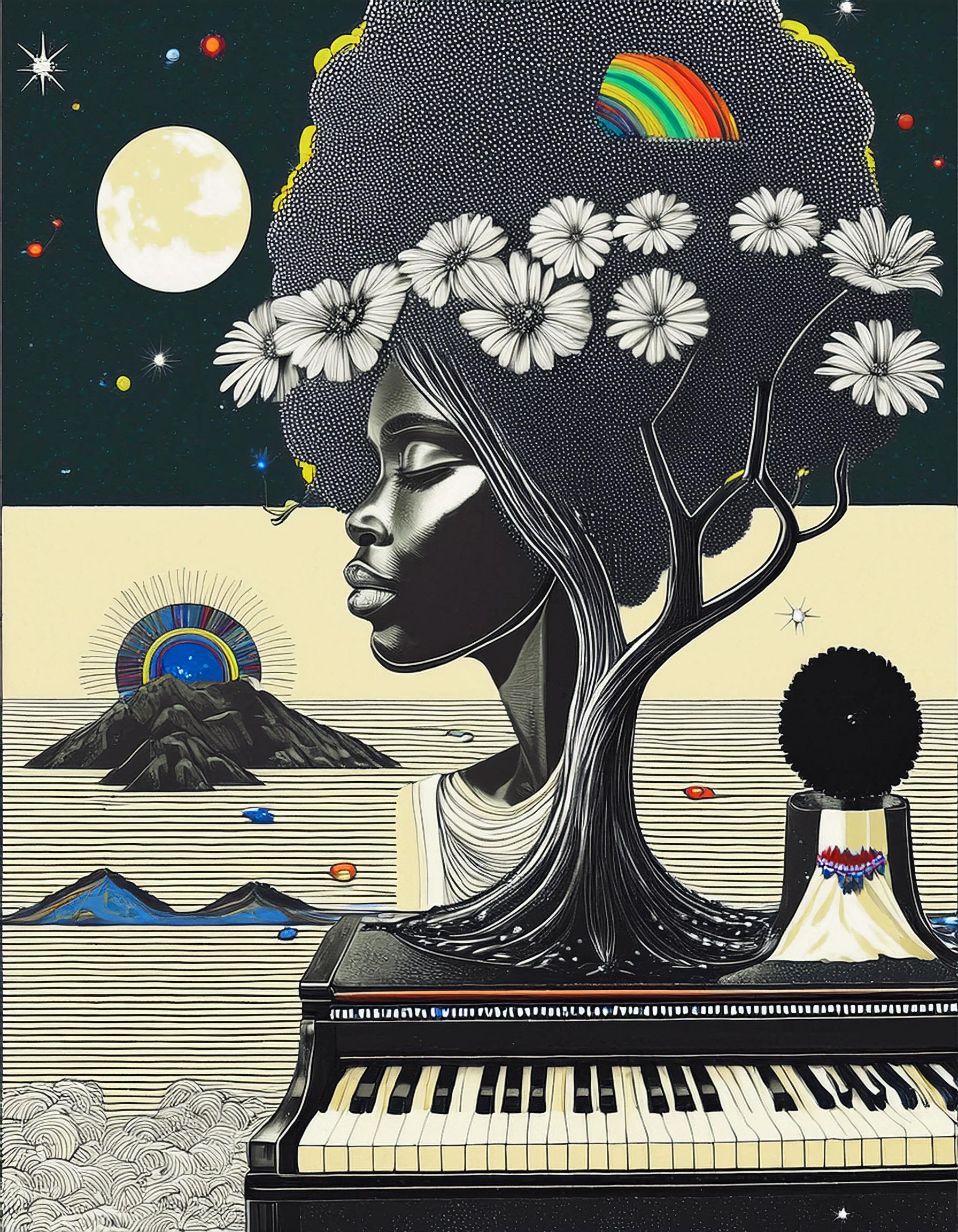

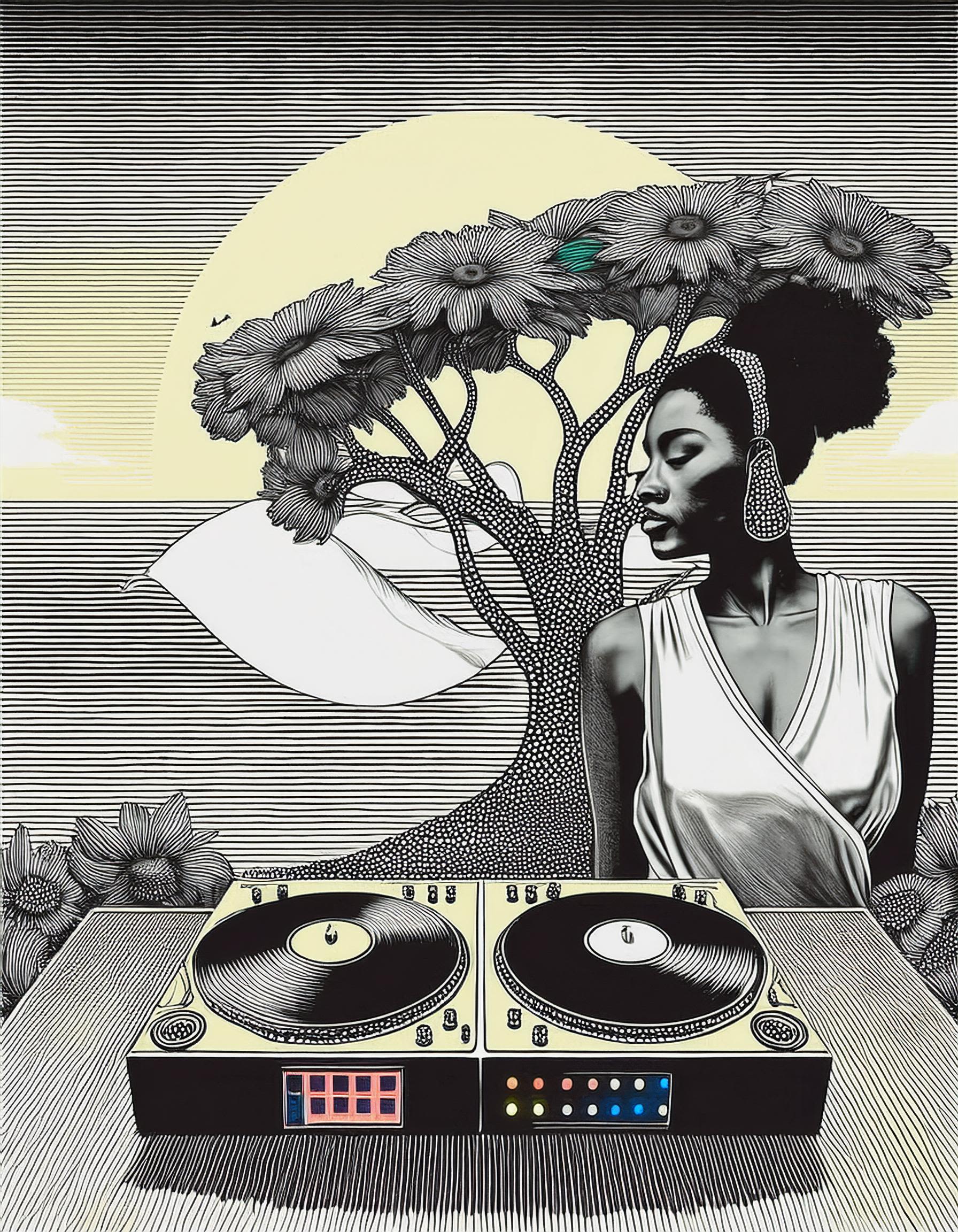

"Iroko" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"Iroko" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

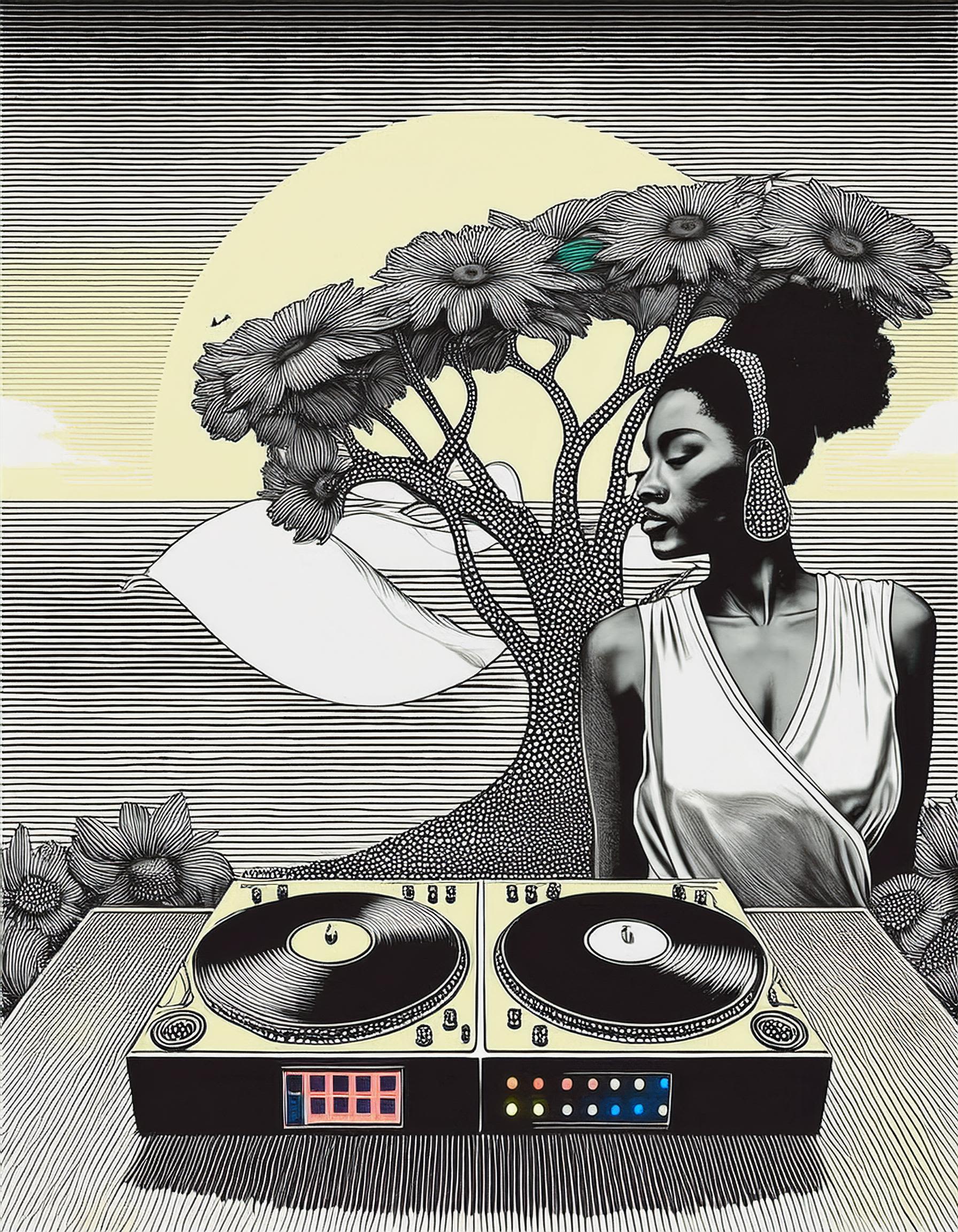

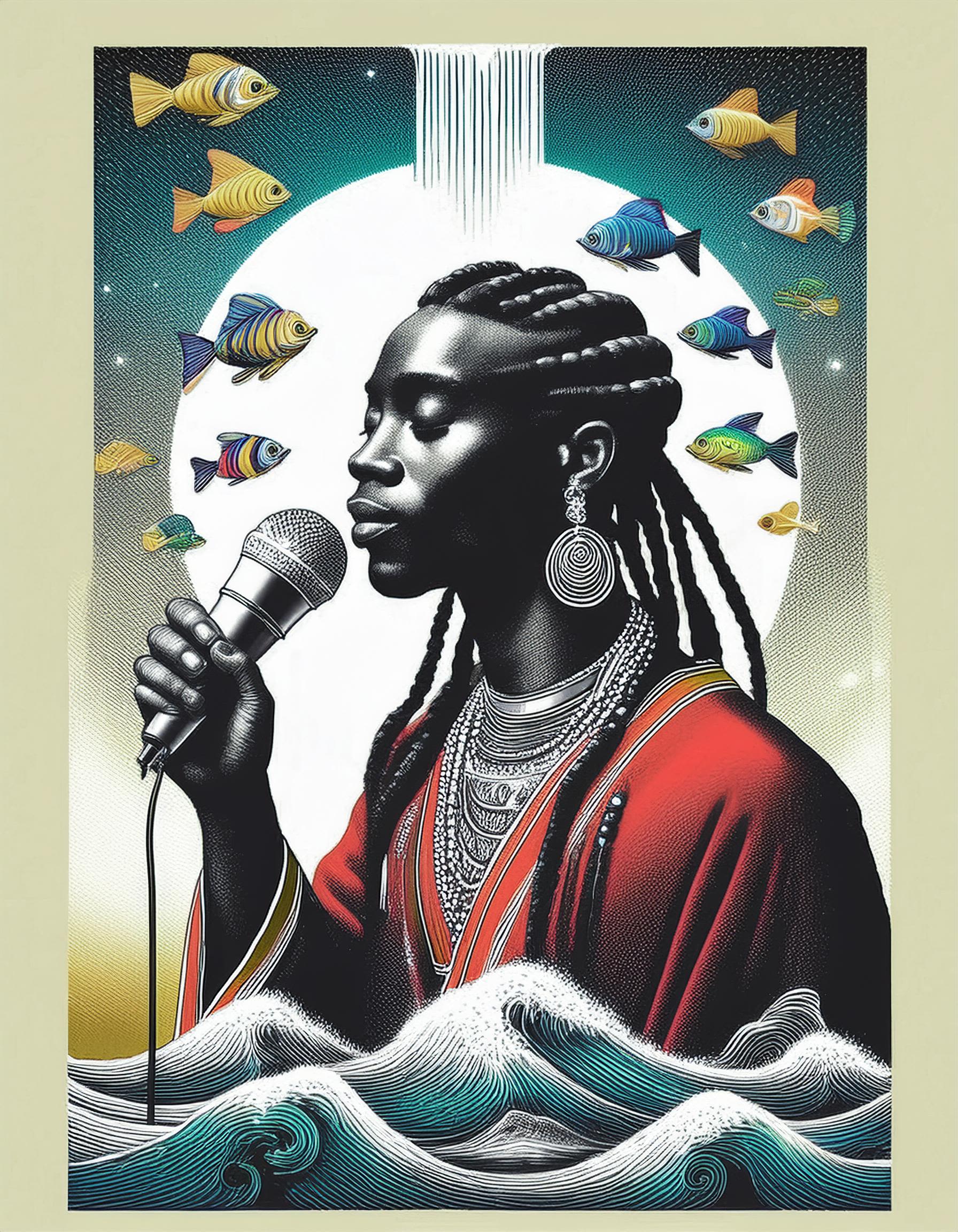

"Zamani 20" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"Zamani 20" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

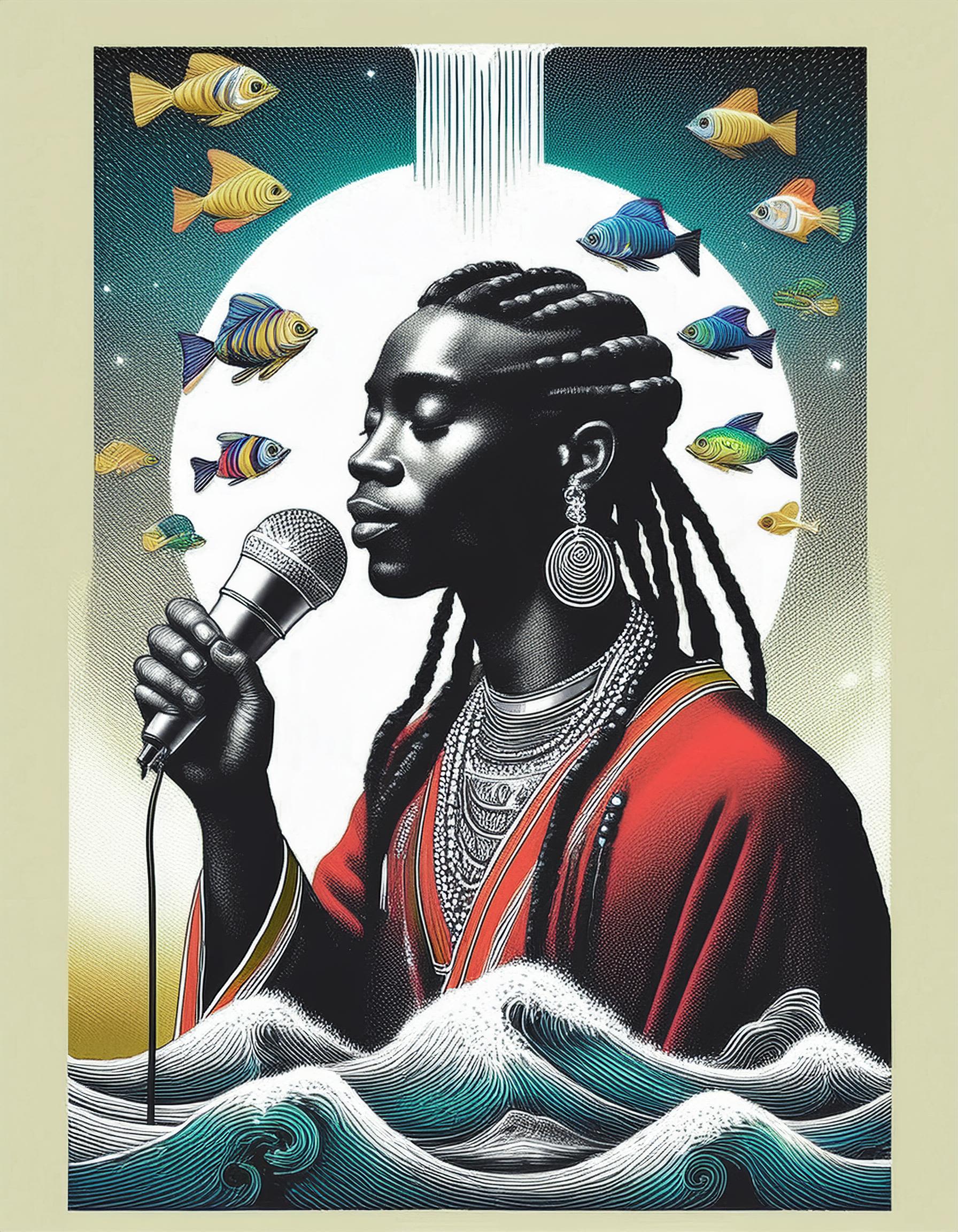

"Zamani 39" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"Zamani 39" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

Crash

In May 2022, Gray-Kontar was co-teaching at Twelve Literary Arts in Cleveland’s Hough neighborhood when his body started telling him something - and it wasn’ t good.

“I was literally in the middle of a sentence, and I just got dizzy,” he said. “So, I went to the hospital.”

Gray-Kontar said his blood pressure was “through the roof” and that the doctors and nurses in the emergency room told him whatever he was doing he needed to stop.

And stop he did.

After groundbreaking events like that summer’s arts and cultural BLK JOY Festival and collaborative projects like “In Search of the Land,” a hip hop album dedicated to his hometown, Twelve Literary Arts closed its doors in December 2022.

"Black Gold" (feat. Ngina Fayola) [Twelve Literary Arts]

Gray-Kontar determined the business side of Twelve Literary Arts was leading to his high anxiety and hypertension. If he didn’t change things immediately, he’d be risking a stroke.

“I got very, very tired,” Gray-Kontar said.

The work had certainly piled up at Twelve Literary Arts, but he admits it was in large part his own fault.

“My ego got big," he said.

"I started to believe that if I wasn’t in the room, then it wasn’t going to be done right. I’m not proud of that person,” he said.

“I wasn’t being especially a good friend. I wasn’t being an especially good son. I wasn’t maintaining my spiritual practice at all, and I let my health go.”

He also was under stress balancing the finances for Twelve Literary Arts.

“I wasn’t able to pay all the bills for Twelve. It was just too much,” he said.

To add to his increasing anxiety, a few weeks after going to the ER Gray-Kontar received a frantic phone call from his mother. Her house had caught fire. She escaped unharmed but her home was severely damaged.

“[I] was grateful she made it out alive, but everything stopped at that point,” he said.

From pastoring to poetry

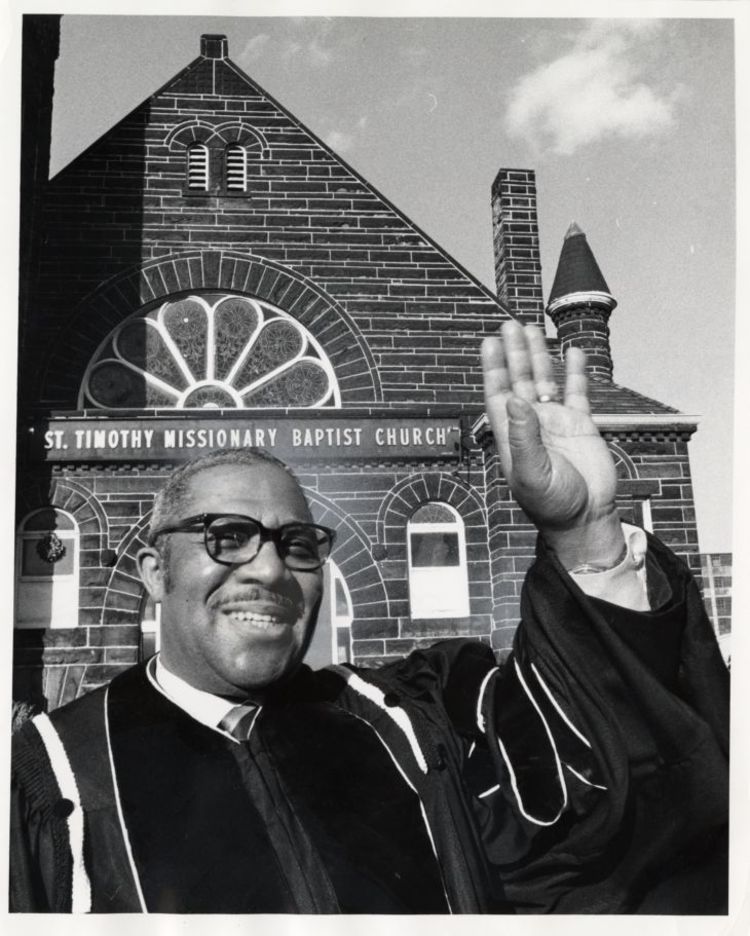

Gray-Kontar’s passion for the spoken word began in the mid 70s at St. Timothy Missionary Baptist Church in Cleveland, where Rev. John T. Weeden preached to a congregation that included him, his mother and grandmother.

“I was about four years old, and I remember Rev. Weeden was pastoring,” he said. “My grandmother, who was sitting right next to me, she started to shout and get happy.”

Four-year-old Daniel was amazed by how his grandmother was overcome by the power of another’s words, and he pointed at the pastor.

“What that meant was, ‘I want to do that.’ I didn’t know what ‘that’ was,” he said.

“The only thing I knew was that this man was reading from this book, and reading from this book was making people experience joy. And I said, ‘I want to do that now.’”

Growing up the only child of a young, single mom, Gray-Kontar attended multiple schools across Northeast Ohio as the two moved from town to town.

“I was raised by an incredible mom,” he said. “I watched my mother grow up like she watched me grow up.”

He attended schools in Shaker Heights, East Cleveland, Cleveland Heights and Maple Heights, where he graduated from high school.

“I went to 11 schools in 12 grades,” he said.

On the one hand, moving around made him a transient kid who had to make new friends each school year.

“But on the other hand, I learned to talk to anybody,” he said.

Recognizing Daniel’s interest in the spoken word and reading, his mother introduced him to the work of esteemed Cleveland poet Langston Hughes.

His grandmother encouraged Gray-Kontar to read his first poem in front of an audience at St. Timothy’s.

“I remember the joy, the pride that folks in the congregation had for this young, Black child poeting at six years old and I never forgot it,” he said. “I guess a poet was born.”

Gray-Kontar’s ability to connect with a variety of people paired with his passion for the spoken word led him to the world of performance poetry where he flourished.

For his contribution in ‘94 to the Poetry Slam win in Asheville, North Carolina, Gray-Kontar said he read a poem he’d written about Langston Hughes in front of a crowd of close to 500 people.

“I left my body,” he said. “I remember I still had the poem in my hands. I was still reading the poem. But as I read it, somehow, I was there, but I wasn’t there.”

After his performance, he left the stage and began to sob.

"I was somehow channeling or connecting to something much, much greater than me," he said. "I never experienced [poetry] in that way before."

Rev. John Weeden of St. Timothy Baptist Church in Cleveland [Cleveland Public Library]

Rev. John Weeden of St. Timothy Baptist Church in Cleveland [Cleveland Public Library]

Daniel Gray-Kontar with his grandmother and mother. [Daniel Gray-Kontar]

Daniel Gray-Kontar with his grandmother and mother. [Daniel Gray-Kontar]

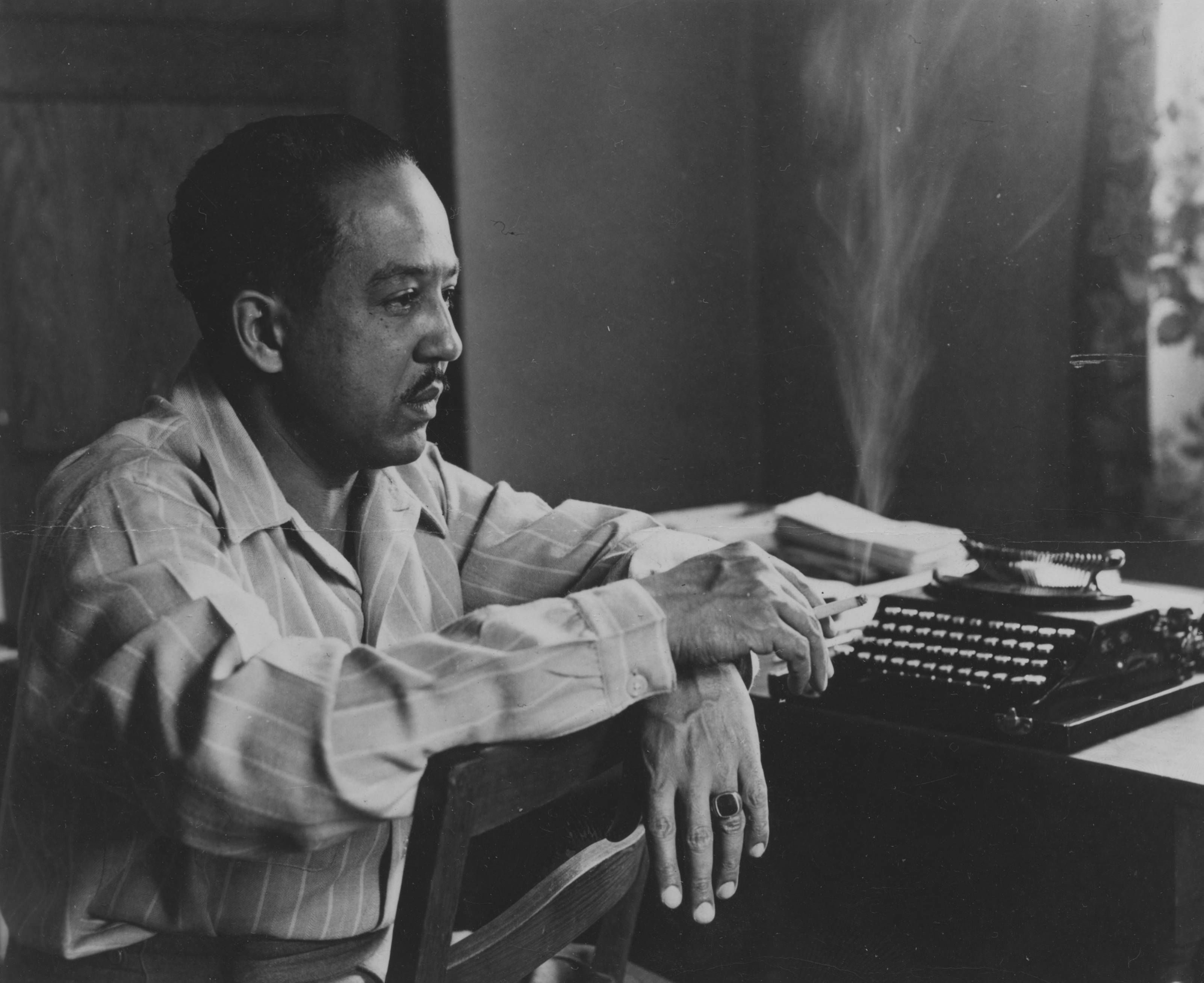

Langston Hughes [Griffith J. Davis / Cleveland Public Library]

Langston Hughes [Griffith J. Davis / Cleveland Public Library]

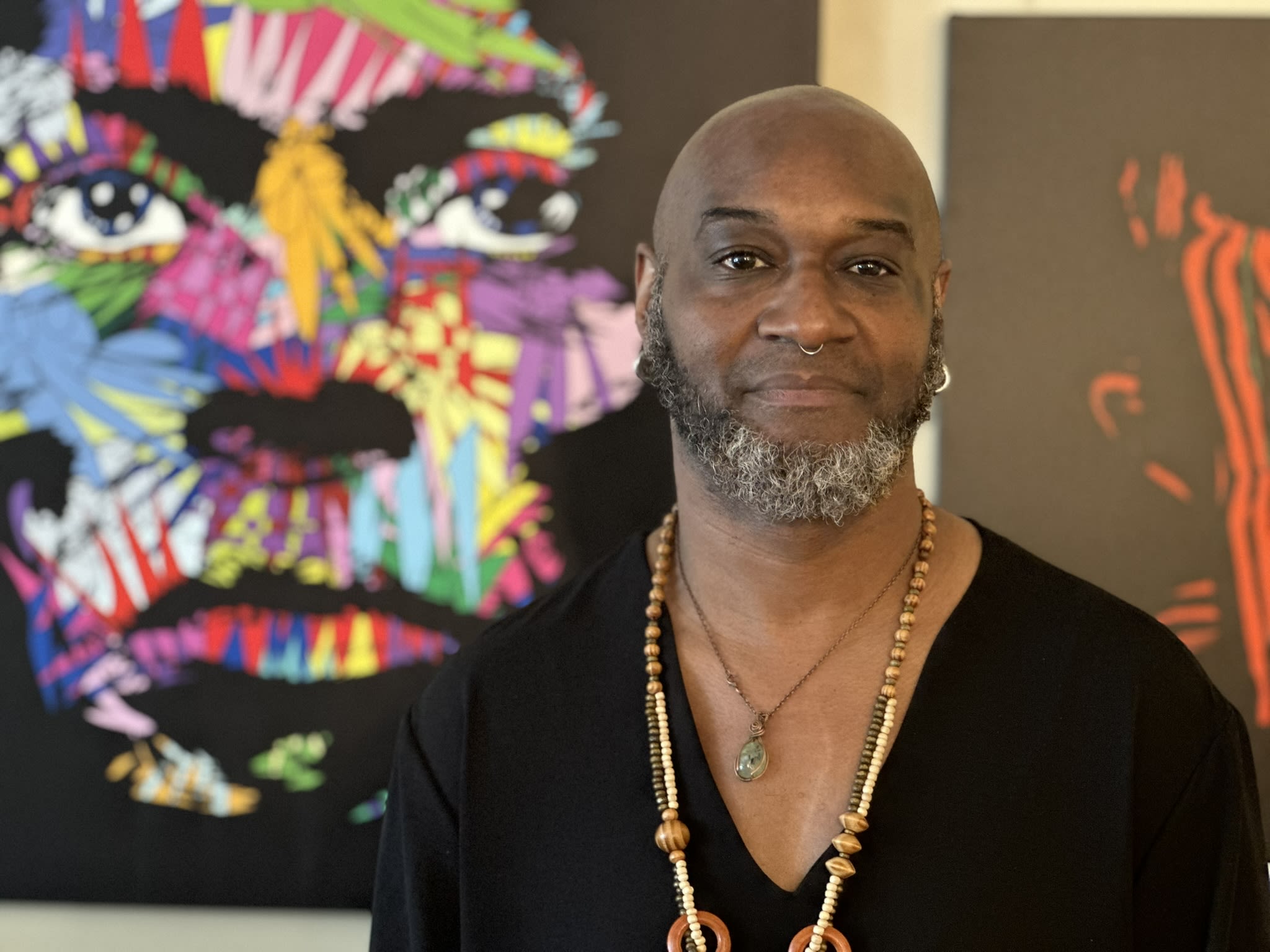

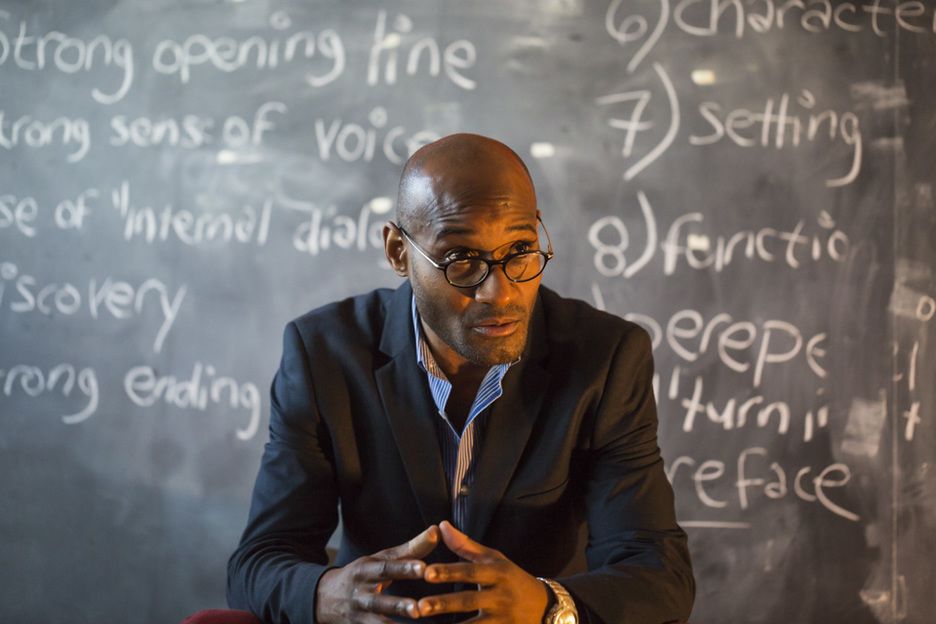

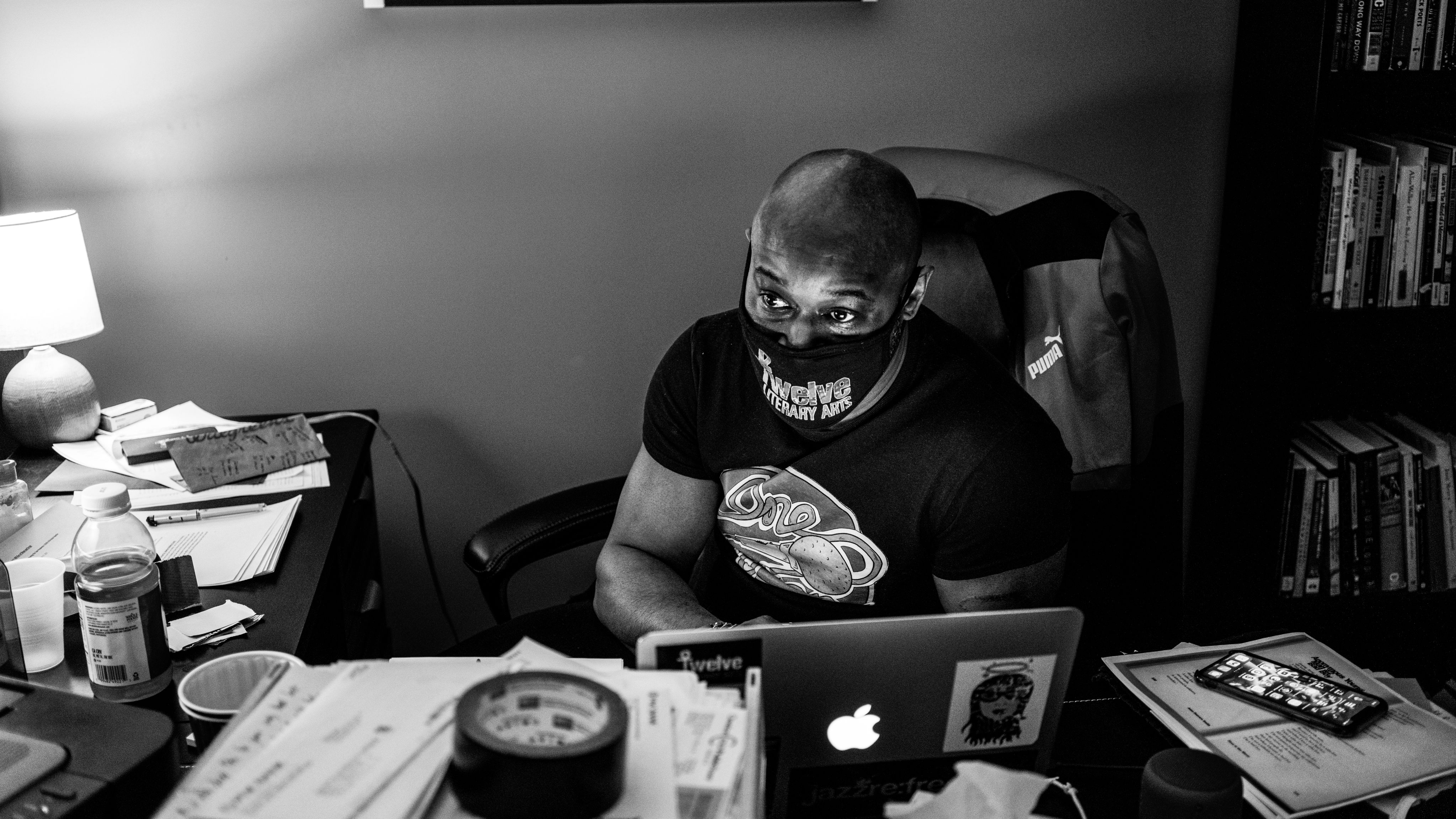

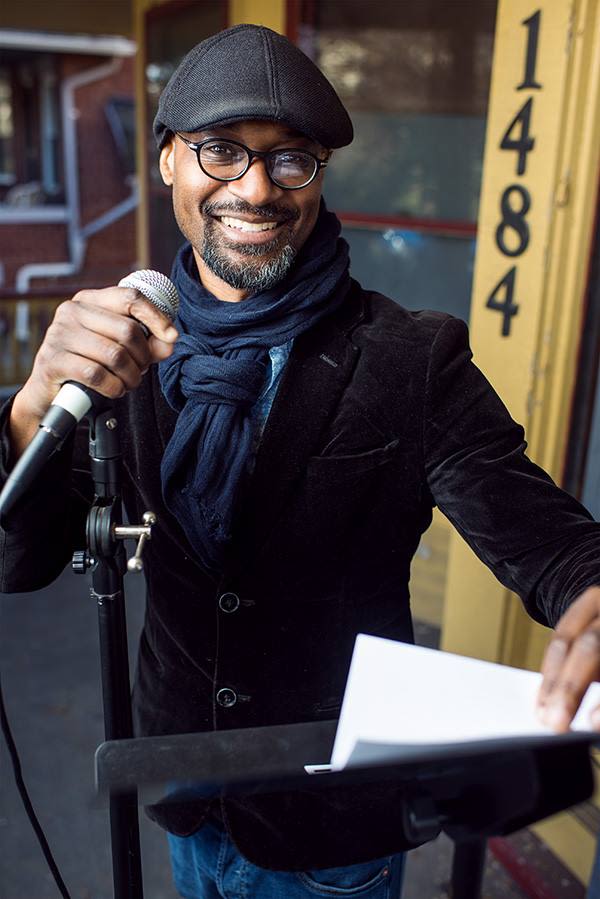

Daniel Gray-Kontar [Billy Delfs / Cleveland Foundation]

Daniel Gray-Kontar [Billy Delfs / Cleveland Foundation]

Art administrator vs. the artist

“If you want to make a living [as an artist,] you have to be the teacher and the artist or you have to be the administrator and the artist,” Gray-Kontar said. “And if you let it, the administrator becomes 70%, and then 80%, and then 90% and then 100%.”

Gray-Kontar reached that point where the time he spent as a creative artist had dwindled significantly.

“There were some weeks I was working 65 hours, 75 hours a week. People started noticing me disappear,” he said.

After years of letting his role as an arts administrator consume him, Gray-Kontar said he feels like an artist again.

Higher ground

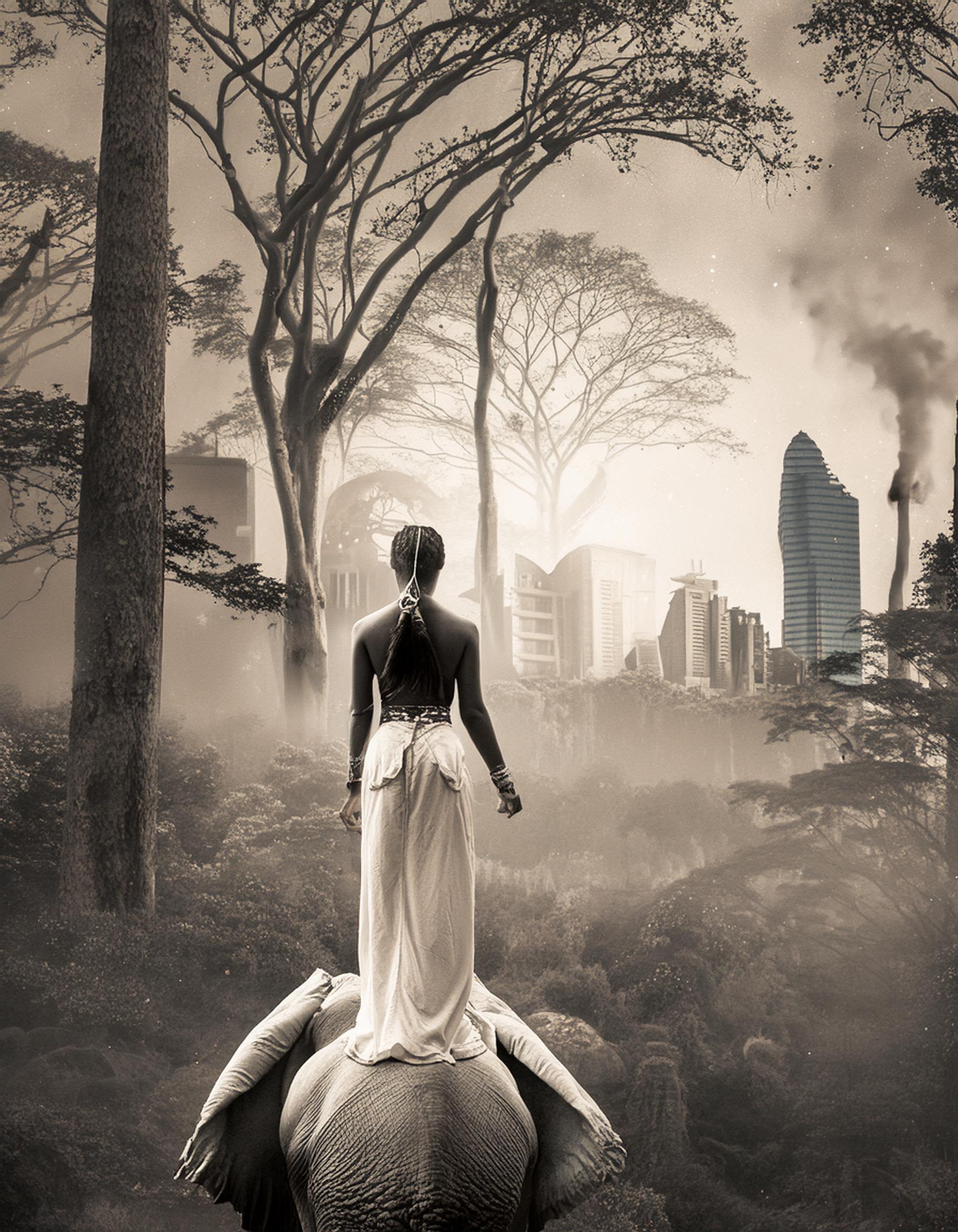

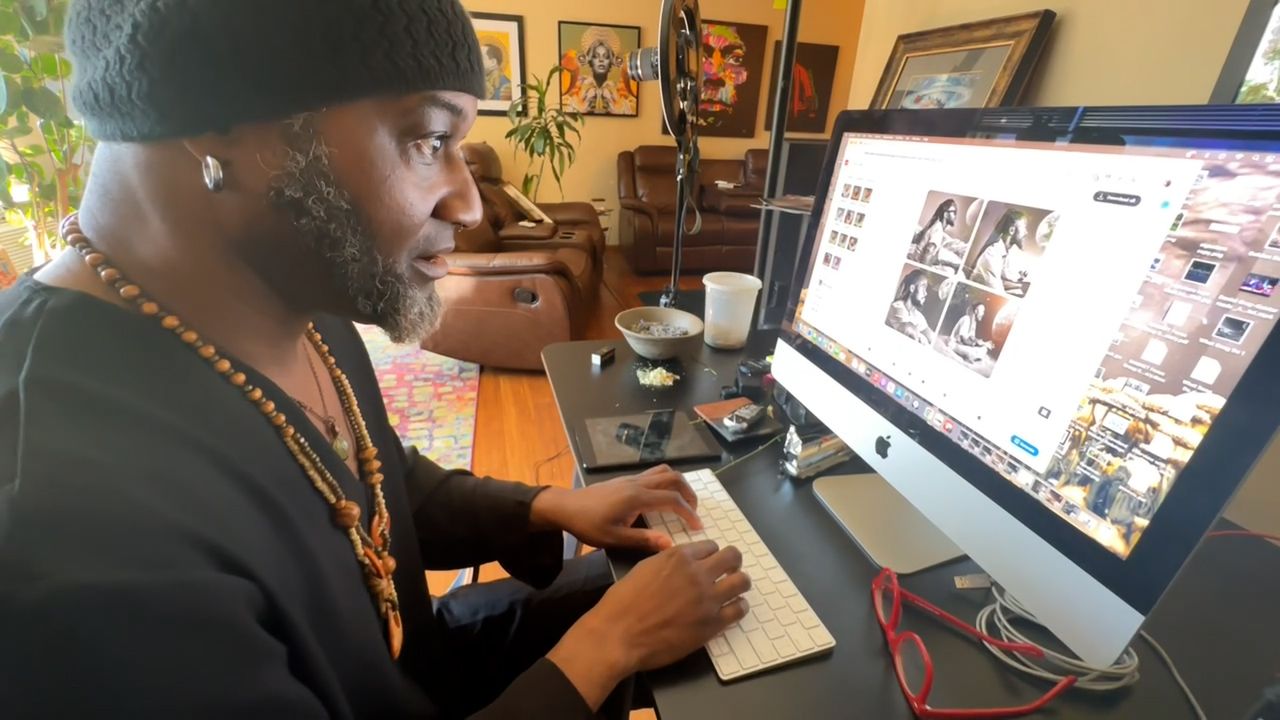

Daniel Gray-Kontar creating AI art in his home office studio. [Dave DeOreo]

Daniel Gray-Kontar creating AI art in his home office studio. [Dave DeOreo]

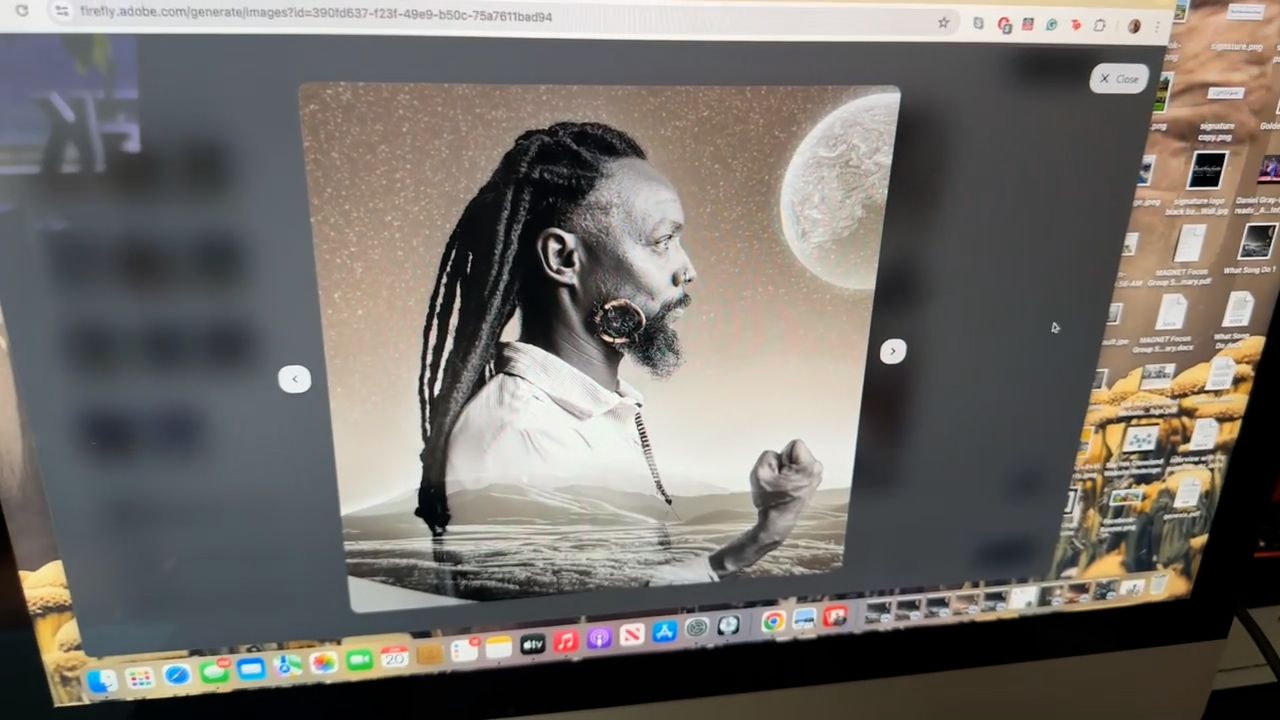

A work in progress by Daniel Gray-Kontar. [Dave DeOreo]

A work in progress by Daniel Gray-Kontar. [Dave DeOreo]

"In progress work" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"In progress work" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

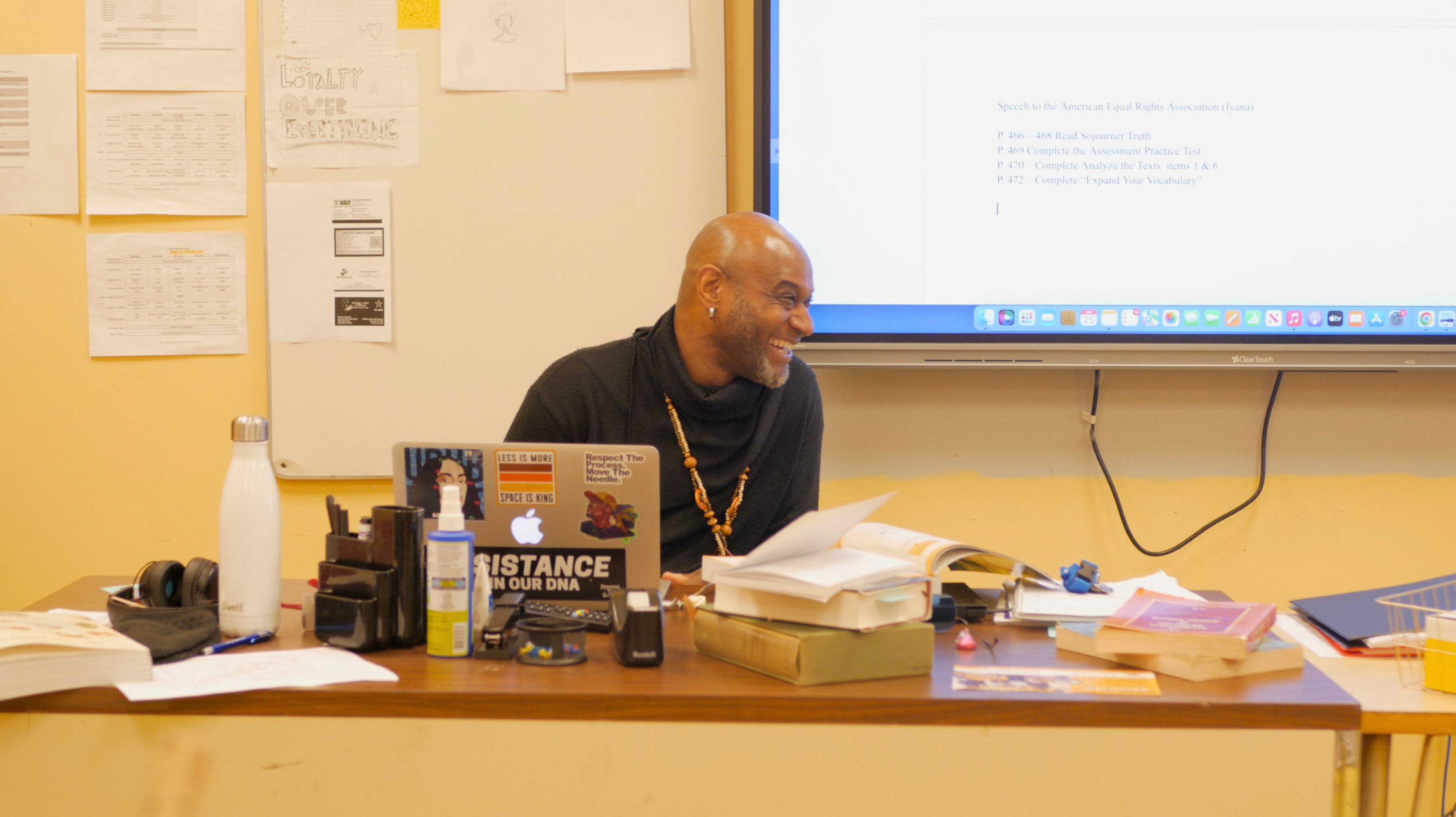

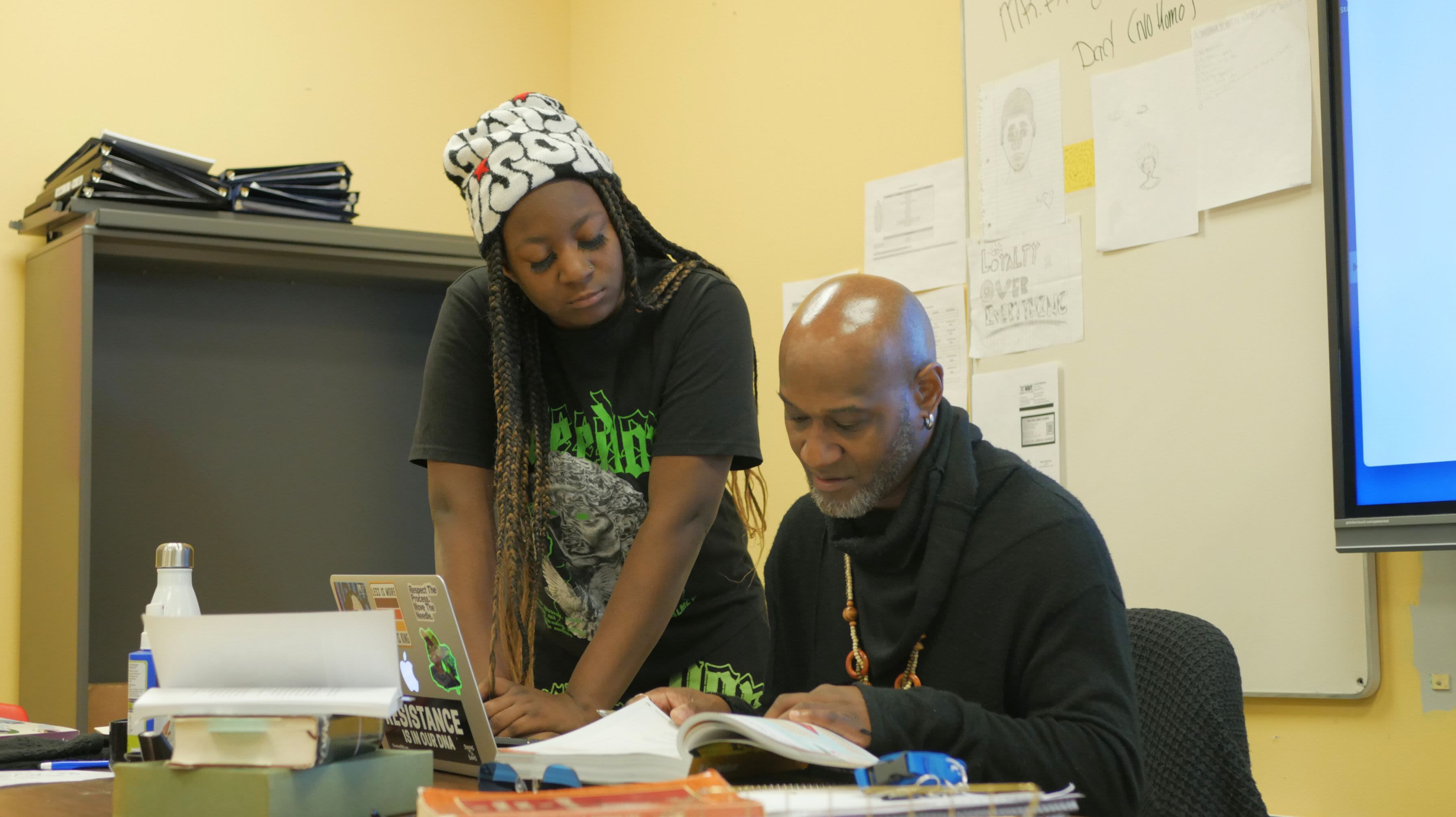

Daniel Gray-Kontar works with a student at Castle High School in Cleveland. [Abby Lekas]

Daniel Gray-Kontar works with a student at Castle High School in Cleveland. [Abby Lekas]

Gray-Kontar’s home office in Lakewood is a creative studio where the organic and the digital mingle. His recording equipment and Mac computer are surrounded by more than a dozen plants. Framed images of Duke Ellington, Miles Davis and A Tribe Called Quest look down on him as he created his Afrofuturist imagery on a recent afternoon.

He quickly typed various prompts into the AI app Adobe Firefly. “Profile of African man with long dreadlocks sitting in a lotus position…background of planet Mercury,” he said as he typed.

AI took the prompt and began making various images that appear on his screen. But the images looked too “AI-ish,” so he adjusted the prompts for more detailed imagery.

“The joy that I started experiencing creating this stuff was just like I hadn’t felt anything like it before,” he said.

“I was like, ‘Oh, I’m a [visual] artist.’”

He also uses AI to enhance his own photographs of his plants, his friends and even himself.

“I’m able to take these images and merge them, until I have the right texture, feeling, structure, mood, mode,” he said. “It’s merging my artistry …with what’s in my head that I can’t draw. It’s like collage work.”

He acknowledged that many don’t think it’s real art.

“They think it’s stealing,” he said and compared it to hip hop sampling.

“We started creating whole other compositions based on what we discovered,” he said. "Same thing with AI art.”

Gray-Kontar has returned to teaching English language arts at Castle High School in Cleveland, a credit recovery school that allows students retake classes.

“I really wanted to go back to teaching and working with young people,” he said.

Parable of the Talents

Looking back on that time when he wasn’t making art, Gray-Kontar recounts a parable from the New Testament, the Parable of the Talents.

“If you don’t use your talents for what you’re supposed to do you will crash,” he said.

“I crashed and then art resurrected me all over again.”

Since his health scare, Gray-Kontar said he has a deeper awareness of his mortality which is influencing his poetry, his visual art and his music.

“I became a much more spiritual person and became much more connected to the spirit and spiritual energy and to nature,” he said. “All of those things are very much present in my work in a way that they haven’t been quite before.”

In the fall, Gray-Kontar said he wants to exhibit his new work by curating a space for the community to engage with his art.

“I hope that once I find a good partner or find a space, that I’m also inspiring people to create more art,” he said. “We need more art not less.”

“If [art] is what you’re really here to do, it not only saves your life, but it is your life.

It is your purpose and I know that my purpose is to create art that brings us closer together,” he said. “It doesn’t matter how successful I am or how renowned I am … it’s about doing what the spirit put me here to do.”

"Friday's Ball 3" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"Friday's Ball 3" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"Funk Natural 32" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"Funk Natural 32" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"Lost in the Flow 18" by Daniel Gray-Kontar

"Lost in the Flow 18" by Daniel Gray-Kontar