Art Saves:

Fatima Matar

champions women

through art

Editor's note: This story is part of a series exploring how art saves people’s lives. Whether someone faces mental illness, systemic social barriers or any other challenges, art in its many forms offers a way to express, heal, transform and find joy.

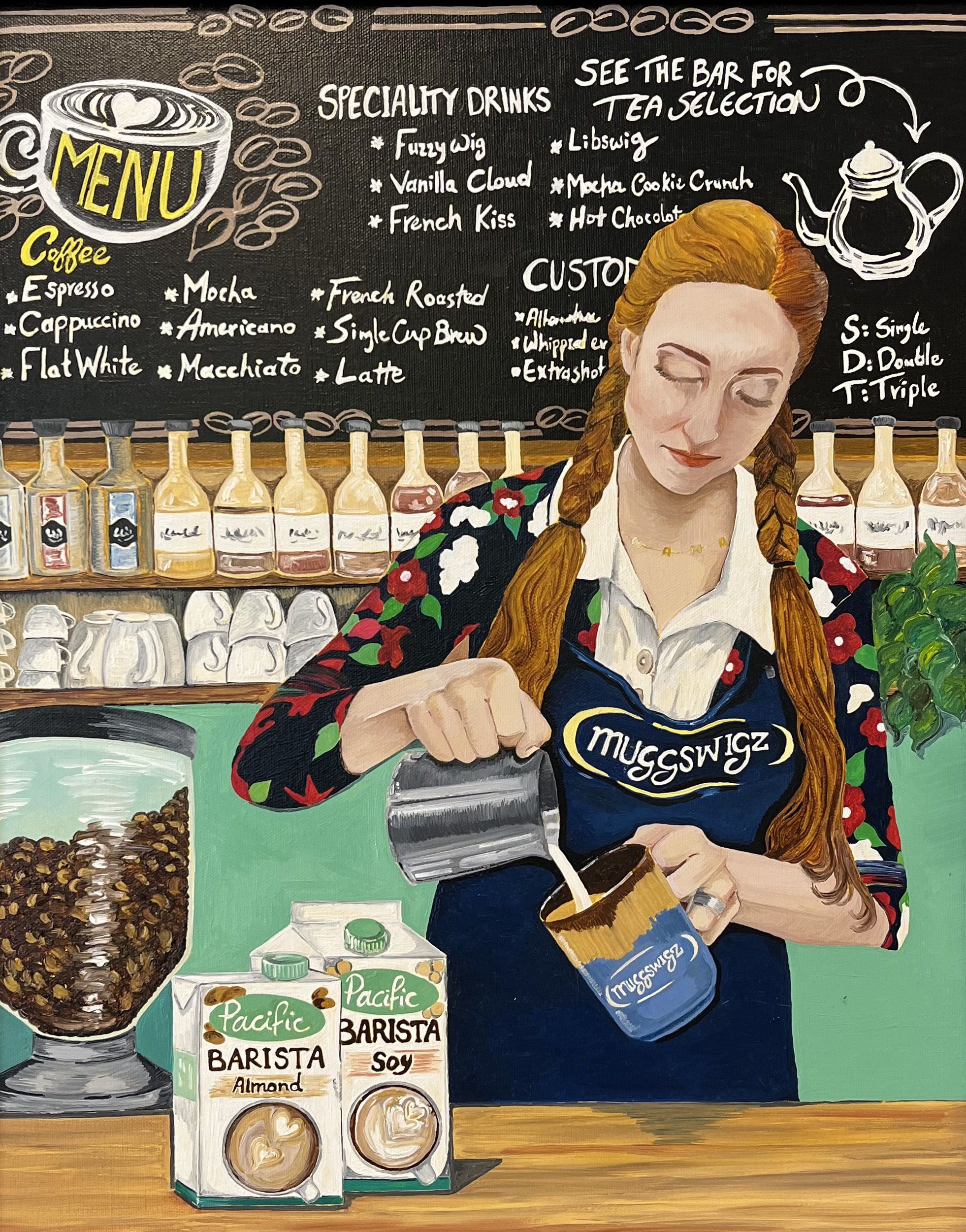

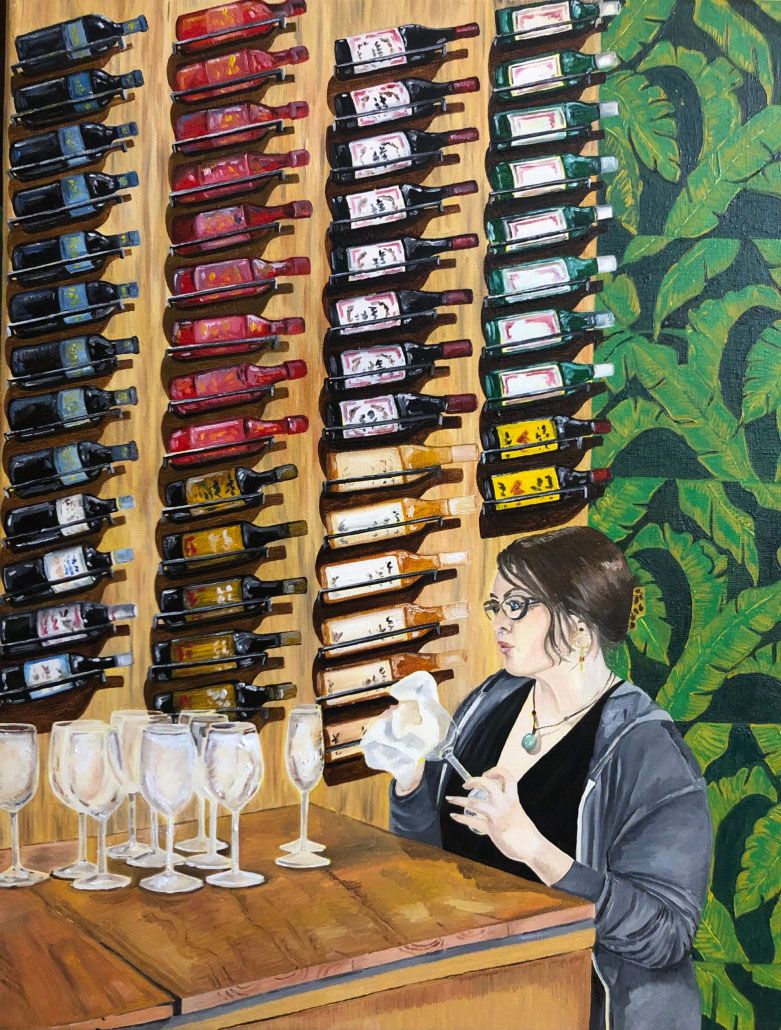

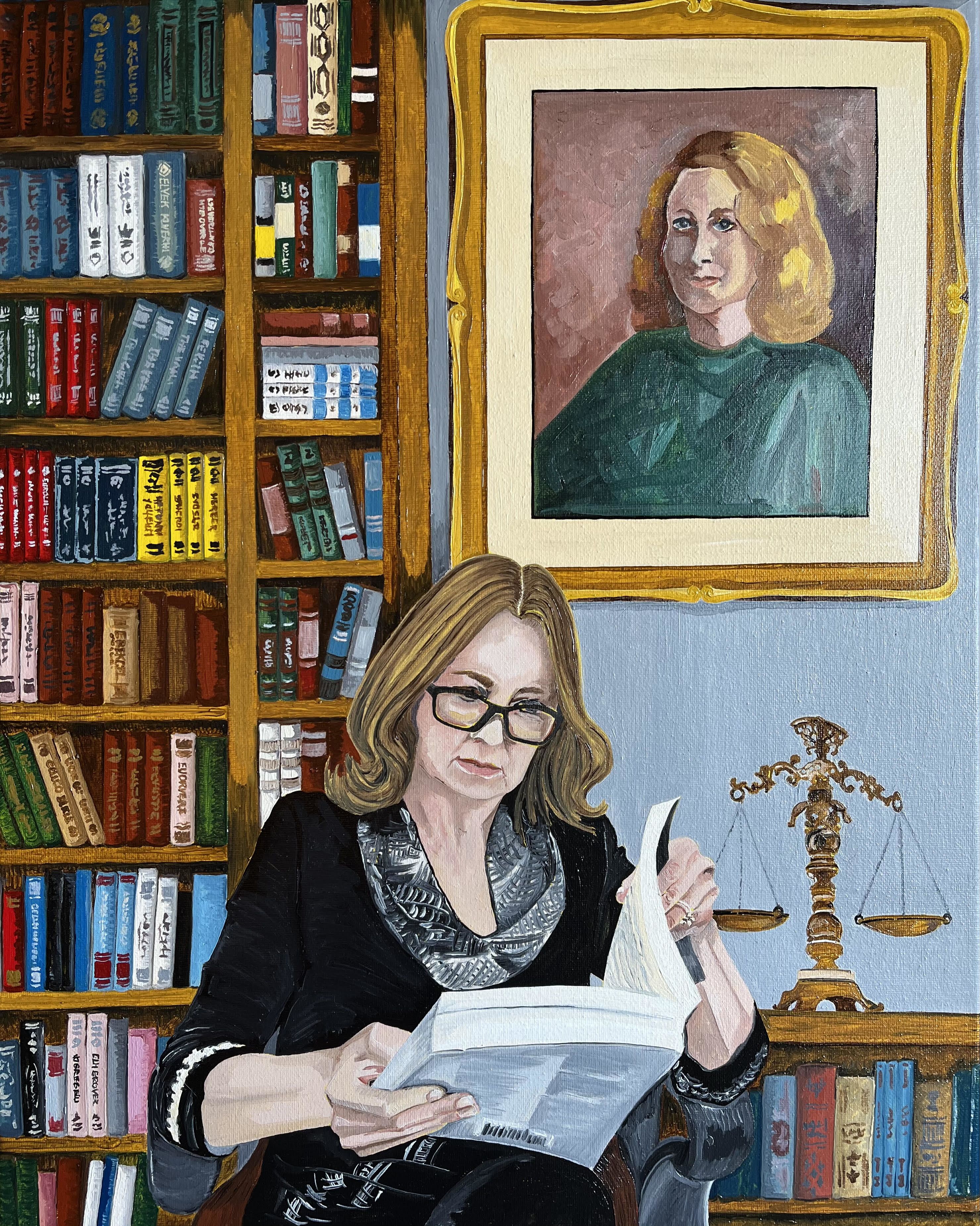

Fatima Matar’s vibrant paintings feature real women doing real work. She purposefully contrasts the plethora of imagery focused on women’s bodies - seen on social media, glossy magazine covers and museum walls - with paintings of women playing piano, washing wine glasses and making coffee.

“We're not only bodies. We are minds,” she said. “Very beautiful, very interesting and very creative minds.”

"The Pianist - Chu Fang Huang" by Fatima Matar

"The Pianist - Chu Fang Huang" by Fatima Matar

Painting is just one of the ways she advocates for women. Her poetry, memoirs and performance art are other outlets for her to express feminism as well as the many hardships she has experienced speaking out in her native Kuwait, seeking asylum in the United States and starting over in Northeast Ohio as a single mother.

Through uncertainty, loneliness and depression, art has sustained her.

“In painting and writing, you forget about time, you forget about other issues that you're struggling with,” she said. “When all of my mind, my eyes and my hands are all engaged in so much harmony to bring a piece of art to life, from nothing to a thing, I find the joy and the satisfaction and the fulfillment I get from that I don't get from anything else in life.”

Sharing her story

Matar is candid about her journey to the United States, sharing details through performance poetry about being detained with her daughter upon their arrival at Chicago O’Hare International Airport in December 2018.

In a 6-by-6-foot room with nothing but one dirty mattress on the floor, three security cameras watching us from every angle and eye-watering, headache-inducing fluorescent lights we aren't allowed to turn off, they take our cell phones and our luggage.

Despite having passports and visas, Mater said she and her daughter were sent to a detention center in Texas.

After they were released, they built a new life in Northeast Ohio. More than five years later, uncertainty still looms as she and her daughter continue to wait for an immigration judge to recognize them as asylees.

My daughter and I are devastated.

We waited and waited and hoped and hoped, and now we are back at square one: our case postponed indefinitely.

However, I won an art grant, and I'm invited to exhibit my paintings at beautiful local art galleries such as Kaiser Gallery, Waterloo Art Gallery and Negative Space.

On a hot night in May, Mater delivered her personal essay “Ask Me” from an unairconditioned room in the Brownhoist, an old office building in Cleveland, during Micro Theater's artist showcase.

Matar’s performance started and ended with an encouraging Maya Angelou quote about not being disheartened by the many defeats one faces in life.

Art and work

Since arriving in the United States, Matar has held a variety of jobs to support her daughter and herself. With a Ph. D. in law and prior experience as a law professor, she initially sought college teaching opportunities.

“When I was rejected from the local colleges, I was like, ‘OK, I could either see this as a rejection, or I could see it as the universe redirecting me,’” she said. “Art and literature were always my great loves, so I put all of my energy and passion and focus into art and my literature.”

To pay the bills, she has worked a variety of jobs, including as a cashier, barista, cook and caregiver. In those jobs, she said she experienced poor pay, poor treatment and toxic work environments. She recently wrote a memoir of her experiences, “The Job Applicant,” which she hopes to publish to generate more conversations about how society treats workers who were deemed essential during the pandemic but are not necessarily respected or paid a living wage.

The high demands of service work taught Matar to protect her energy reserves so she can also work on her art. She has found a better balance working part time as a house cleaner, which allows her flexible hours and time for her art. At cleaning jobs, she also can put on headphones and get to work without facing issues like sexism or bullying.

She has further championed service industry workers through her series of paintings of women working.

"The Barista - Morgan" by Fatima Matar

"The Server - Whitney" by Fatima Matar

A mind of

her own

Growing up in Kuwait, Matar said feminism wasn’t discussed. But she quickly learned how life was different depending on your gender.

“There were no books accessible to me that were about feminism or misogyny or sexism. There were no movies. There were no cartoons. There was nothing to get me those ideas. It was just an organic anger that was within me,” she said.

In her youth she noticed inequities in family life, such as women preparing and serving food, hiding in another room while men ate and then getting to eat leftovers and clean up. When she questioned this, she said she was silenced.

Later in life as a law professor, she felt compelled to speak out about a host of issues, from government book bans to so-called honor killings to the rights of the stateless in Kuwait.

“I felt like if I wasn't talking about freedom of speech, and I wasn't talking about diplomacy and I wasn't talking about equal gender rights, who will?” Matar said.

Matar faced legal charges twice for speaking out on social media. She said she was put on trial for criticizing Kuwait’s emir, which resulted in a $5,000 fine and signing a pledge not to repeat the offense in 2012. Six years later, she posted a joke to draw attention to the lack of gender equality in the country. Facing new charges and not expecting any leniency again, she said she fled to the United States for her and her daughter’s safety before the second trial.

As a writer and an artist in Northeast Ohio, she continues to point out injustices, particularly for women.

“I'm focusing a lot on sexism, misogyny, women's rights, women's freedoms, because unfortunately in America right now women are fighting so hard to have autonomy over our bodies and our minds. It's a shame, but that's the situation right now,” Matar said.

Advocating for women

Like with the paintings of women working, Matar further celebrates the creative minds of women with her series of paintings of women reading.

She depicts women reading in real-life settings, dressed naturally and comfortable in their environments, whether at work or on a park bench.

“Throughout our history, men have painted women for their bodies. So, you see a lot of beautiful women - a lot of beautiful white women - nude and draped on love seats,” Matar said.

More paintings of women active in their daily lives displayed on the walls in art museums could change perceptions of women, she said.

Her paintings also call attention to harassment and physical violence in both professional and personal life.

She has a series of paintings of old, ornate doors that have different scenes visible through the keyholes.

The viewer must look closely to see what is going on, from sexual advances to partner abuse. And the view is sometimes obscured, as accounts of what transpired can be fragmented too.

“The problem has always been we have never shed enough light to understand the breadth of the issue,” she said. “The reason why the doors are old fashioned is to portray or to convey that women have… experienced domestic violence for as long as there has been marriage. And women have experienced sexual harassment at work for as long as we have been working.”

Through her performance art, she further explores issues like these. Most recently, she delivered “Confessions of an Angry Feminist” at BorderLight Theatre Festival in Playhouse Square in July.

“The performance poems in this show are … about the patriarchy and sexism and misogyny and the microaggressions and the sexual harassment I've experienced,” she said.

Performing poetry with dance and musical accompaniment, Matar shared myriad examples of sexism in daily life, from blond jokes told at the family dinner table to age-defying creams marketed at the mall.

She challenged the common practice of referring to a single parent's home as broken.

"My home is not broken just because a man doesn't live in it," Matar said.

She also questioned the influence of dolls on young girls - noting that Hello Kitty doesn't have a mouth.

Art as a 'companion'

Not knowing when or if her immigration status will change feels like “the earth shifting beneath your feet constantly,” she said. “You need something to ground you.”

Art has been a constant “companion” through difficult trials.

“When I'm painting, I'm my best self. Or when I'm writing, I'm my best self. Because I'm grounded and I have everything I need,” she said.

Expressing her stresses and pain through painting and writing brings relief.

“It's released into the world,” she said.

The financial payoff isn’t there yet. She’s trying to find an agent and publisher for the two memoirs she has written, the one about working various jobs since she came to the U.S. and another about her journey here. She won an Ohio Arts Council grant this year and has sold some of her paintings, but she still needs other part-time work to live.

“The only way to support an artist is to pay them,” she said.

Matar regularly spreads the word about her art on Instagram. Her paintings have been exhibited at local galleries, cafes and most recently at the Chagrin Falls library. In addition to recent performances with BorderLight and Micro Theater, she performed at Cleveland Public Theatre’s annual Station Hope celebration.

She dreams that one day her art will support her financially so she can focus on creating.

“We need storytelling as humans, and it's the oldest form of sharing information and creating community,” she said. “All of that I find extremely beneficial and really satisfying.”