Art Saves: Michael Boyd Roman

draws from his history

Editor's note: This story is part of a series exploring how art saves people’s lives. Whether someone faces mental illness, systemic social barriers or any other challenges, art in its many forms offers a way to express, heal, transform and find joy.

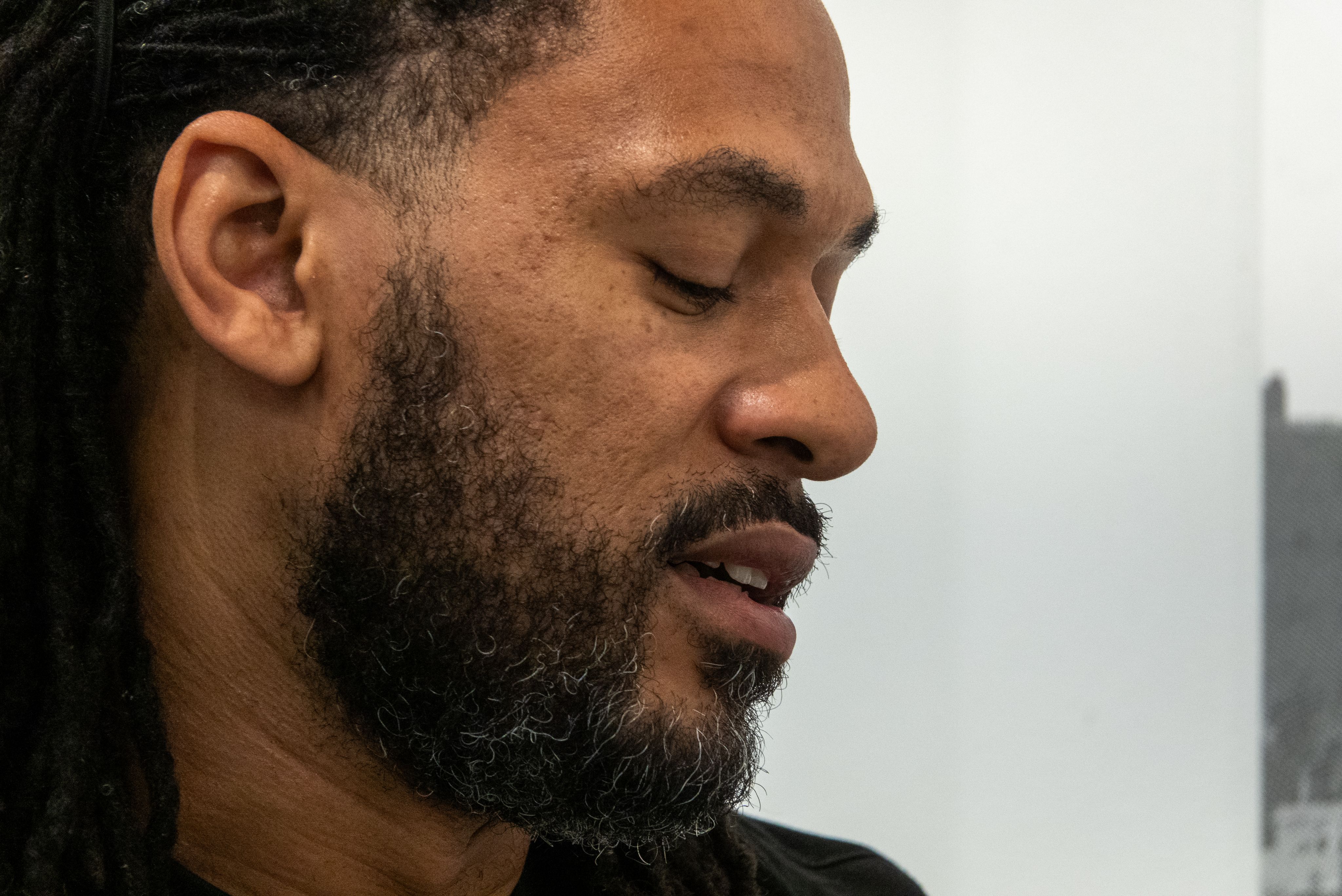

In the heart of Oberlin, there’s a nondescript building which looks like it was plucked from the 1970s and deposited on a sleepy residential street. There’s no signage around the beige-on-beige former auto garage. Step inside and you’ll find artist Michael Boyd Roman. He works in charcoal to convey the dynamics of power: Racial, physical and even spiritual. Art isn’t just his vocation - it’s been his refuge through some very dark times.

“Drawing helped me kind of stay small and out of the way,” said Roman. “I can't think of a time that I wasn't drawing. A sketchbook, paper and pencil has been my escape for as long as I can remember.”

Now in his early 40s, Roman is an assistant professor of Studio Art and Africana Studies at Oberlin College. His work has been displayed in galleries around the country, including Oberlin’s Allen Memorial Art Museum. He is an artist-in-residence at the Akron Soul Train on August 28 and opens the show “Worth a Negus’ Wait in Gold.” Negus is the name for the character, the smallest giant, seen in his art. The show is “about the tension between hyper visibility and invisibility,” he said.

“I am a 6’4” Black man with locks past my shoulders,” he said. “And yet, routinely, and especially in public spaces, I'll get bumped into or cut off or things like that. I don't even mean driving. I just mean walking through a crowd, and someone will say usually something to the effect of, ‘Oh, I'm sorry. I didn't see you.’ Yeah, no. The politics of my body make that almost impossible.”

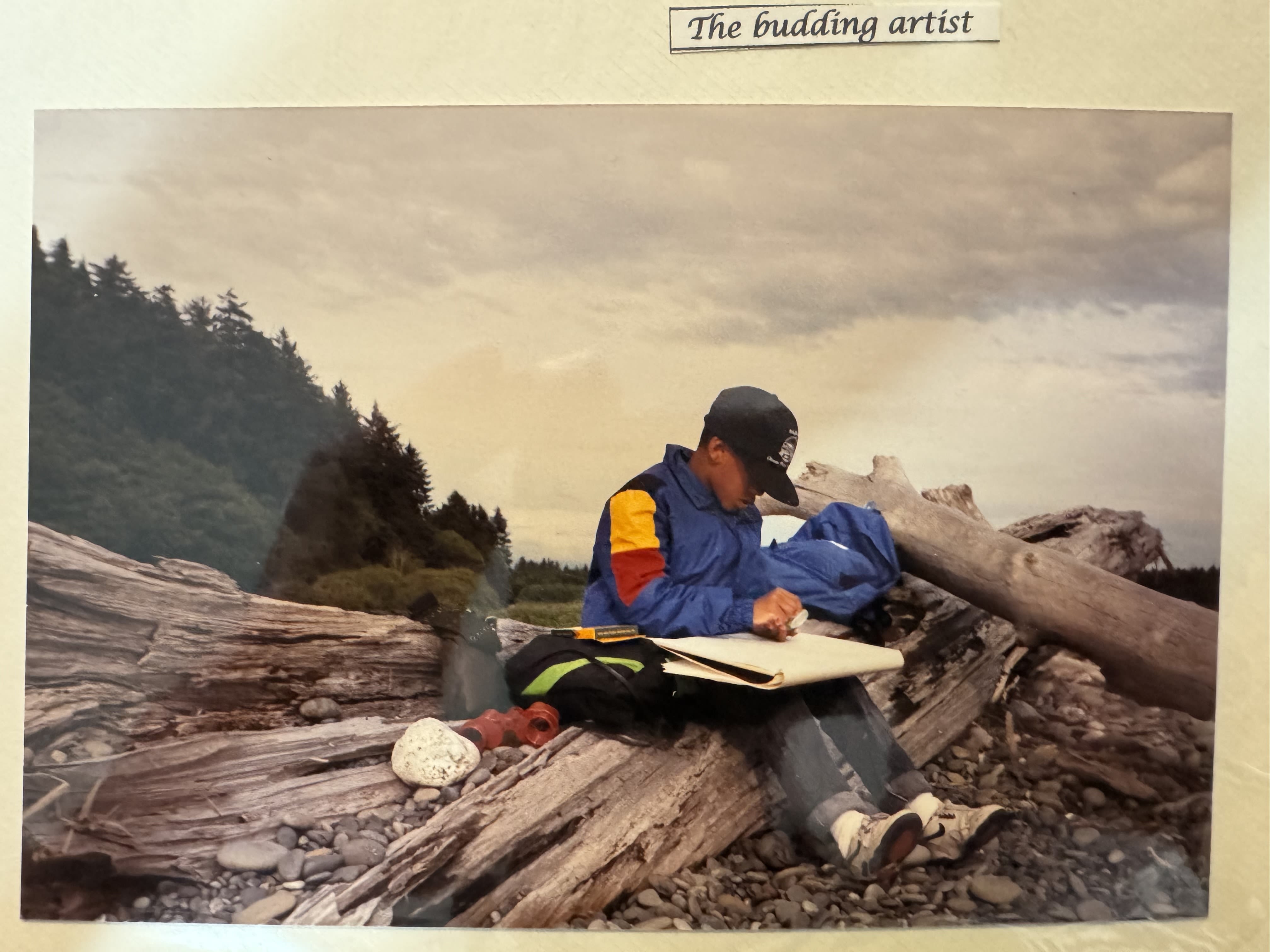

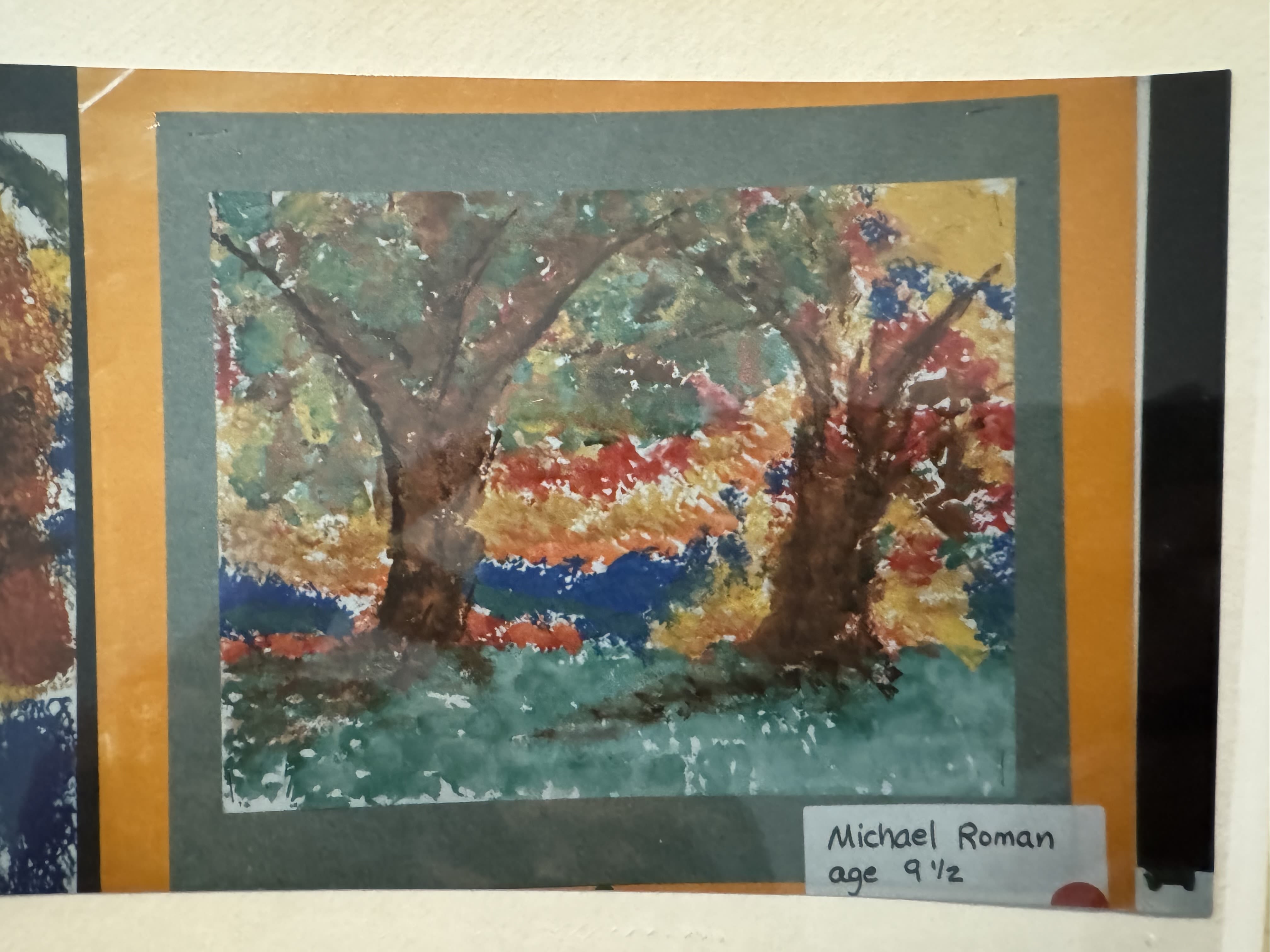

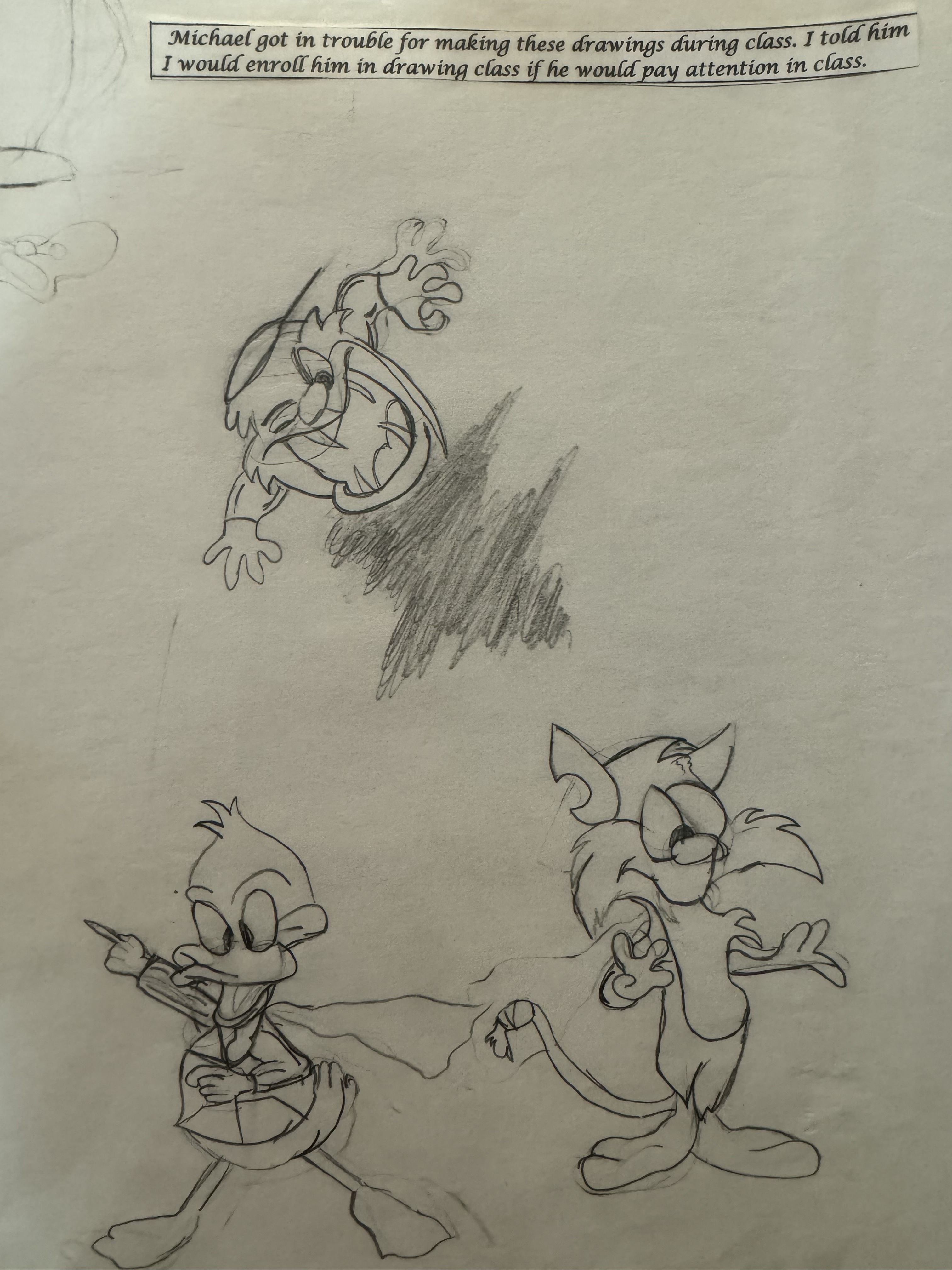

Roman recalls being awarded a prize for this painting at age 9, his first inkling that he could be an artist.

Roman recalls being awarded a prize for this painting at age 9, his first inkling that he could be an artist.

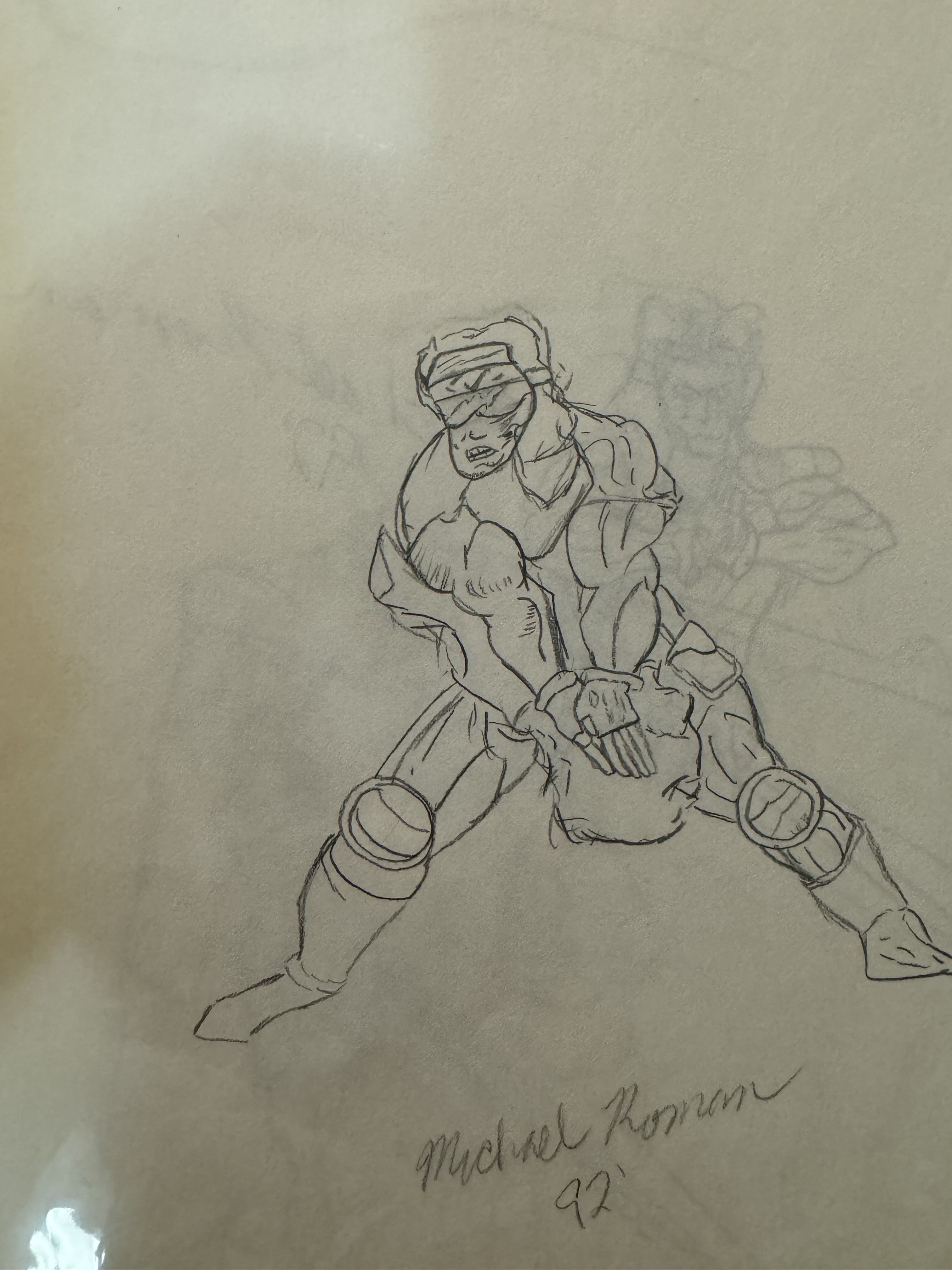

By 1992, Roman's work was heavily influenced by the comic books he bought every week.

By 1992, Roman's work was heavily influenced by the comic books he bought every week.

Drawn into art

Roman is one of several Oberlin faculty members with a studio in the building. The gleaming white space is about the size of a semi-truck. It’s his refuge, as was his bedroom while growing up in the 1980s and ‘90s.

“This is always a little hard to talk about,” he said. “The simplest way to describe it is that I was raised by a bipolar mother, who really didn't get a handle on her ... illness until really about high school for me. And then my father, who did his best with what he knew, but by most standards… could be considered abusive. So, I spent a lot of time alone, oftentimes finding that isolation was safety. There was no one to hurt me. I didn't have to… navigate anyone else's feelings.”

Growing up, while his friends were playing video games, he found that art supplies were cheap and plentiful entertainment.

“I could do anything within the confines of a sheet of paper,” he said.

His talents started to be recognized in grade school, but Roman is modest.

“If there was any real talent, it's that I enjoyed being bad long enough to get good,” he said.

Roman credits his mother with helping him improve.

“She fought to get me into adult drawing classes at the local community centers,” he said. “One summer, there was a summer arts camp and she worked as a custodian for that camp in exchange for me being able to go. She couldn't pay for it, and I had no idea this was happening at the time. I would just be walking down the hall, and I'd see her coming out of the janitor's closet with the mop.”

When he started getting an allowance, he sought out comic books.

“I spent all my money on comics,” he said. “With the $5 allowance, that would last me the week. I'd read them two or three times in that week.”

His favorite was Spiderman. Just like Peter Parker, Roman experienced some upheaval in his personal life: In third grade, he moved across the country to his father’s house in Atlanta.

“That was just a major change across the board,” he said. “He had very specific rules that I didn't always know, and the punishment for breaking those rules was always the same.”

Art became his refuge, and Roman is unflinching in his assessment of what could have happened without it.

“The most immediate and honest answer is I probably would have committed suicide,” he said. “I spent some time hospitalized for suicidal ideations as a rising 6th grader. I just didn't see any other way out. It’s not a question of, ‘Could you really be?’ It’s a matter of a loss of open options. I did not see my circumstances changing, and I just wanted it to stop.”

Roman feels his parents emerged from the experience with a greater understanding of their artistically gifted son. And with therapy, he learned to pick his battles and channel his emotions into his work. His parents became more supportive as he grew up.

Following the universe

“The universe guides you where you're supposed to be,” he said.

That led him to more art camps, college at Syracuse University and a career in the art and art education worlds in Maryland, Maine, California and Georgia. Without art, he wonders if any of that would have been possible.

“I definitely could have fallen in with the wrong crowd,” he said. “There were moments where you want to be cool with the older kids. And they're running off to do something, and I was told, ‘No, you can't come with us. It's not because you're not cool. It's because you’re going to get out of here. You're going to make it. You're not going to risk your shot running around being stupid with us.’”

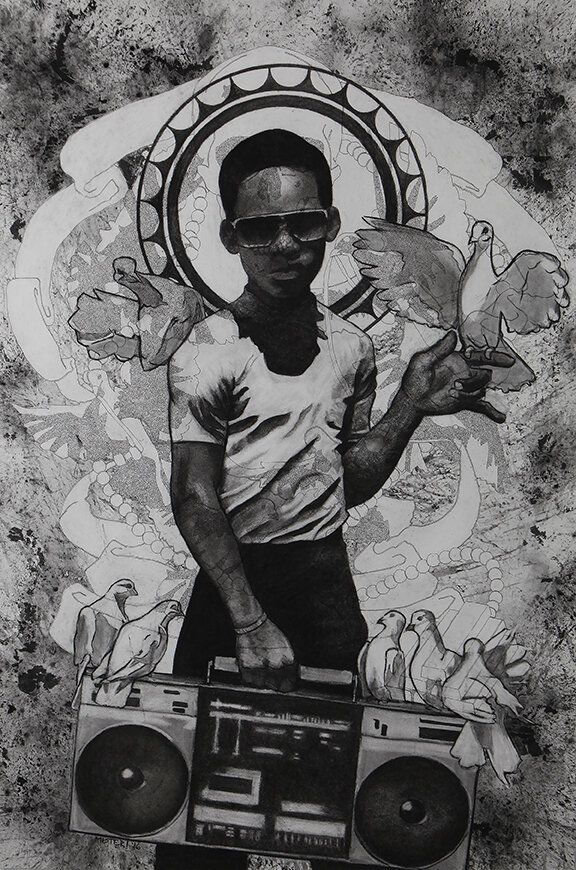

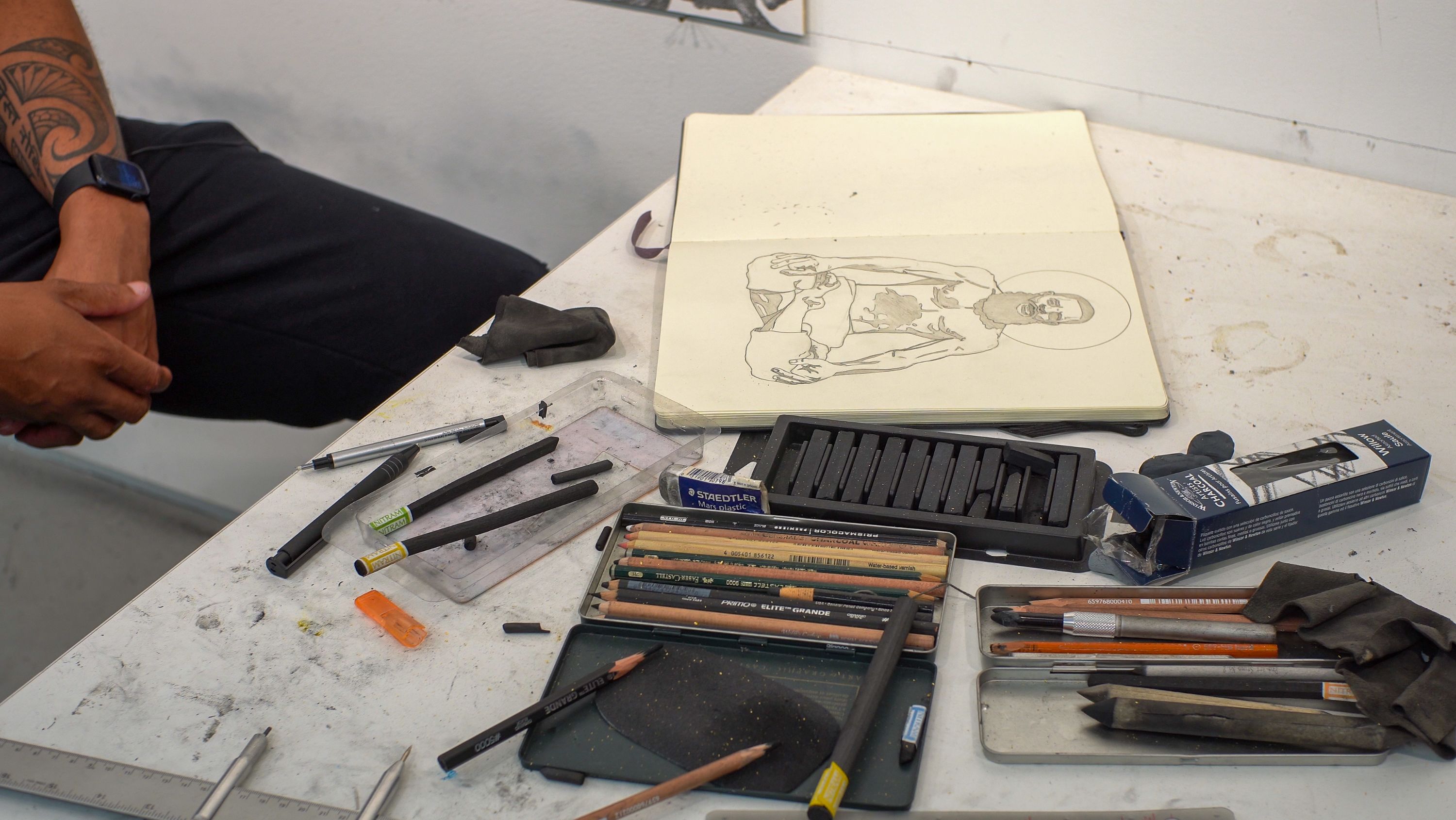

Roman has been working this summer on pieces for a show at the Akron Soul Train, "Negus Wait in Gold." [Ygal Kaufman / Ideastream Public Media]

Roman has been working this summer on pieces for a show at the Akron Soul Train, "Negus Wait in Gold." [Ygal Kaufman / Ideastream Public Media]

There were trying times in his career too: Transitioning from computer animation to painting at Syracuse, trying to establish himself in the Atlanta art world which he found “insular” and mass teacher layoffs in Georgia. Again, he found that the universe led him to where he should be.

“My painting was not progressing the way that I liked,” he said. “I had that moment where you toss the table and make a big mess and storm out. A day or so later, I came back to clean up and found an old pack of charcoal and small pad of paper. After I finished cleaning up, I pulled it out and said, ‘Let's play around with something non-comical.’ I absolutely loved it.”

Drawing inspiration

He’s made charcoal his passion while teaching at Oberlin for the past three years. One side of his studio is lined with bookcases, on which he keeps a few binders full of images for inspiration. Some are saved from magazines and others are his own sketches on scratch paper, but all of them embody the concepts in his artwork and thought process: Spirituality, history and hip-hop.

“I could probably trace this back to undergrad, but my work has always been about exploring my own relationship with personal power,” he said. “Divinity is what I choose to call it now. Way back, I was still very much invested in comic art and language. So, I was drawing and painting people flying through the air and action sequences from comic books. And it was about seeing yourself with a certain level or type of power.”

Roman hesitated when asked if it all goes back to his upbringing of feeling powerless.

“When I'm thinking of impact, I'm usually making work for 19-year-old me before I make work for anyone else,” he said.

That moment – age 19 – ignited his ambitions.

“I had to take two separate art history courses for the entire year,” he said. “I didn't see myself represented in the class. I didn't see myself… as a subject of art or as an artist. I didn't see myself represented, and so it was really disheartening to think about.”

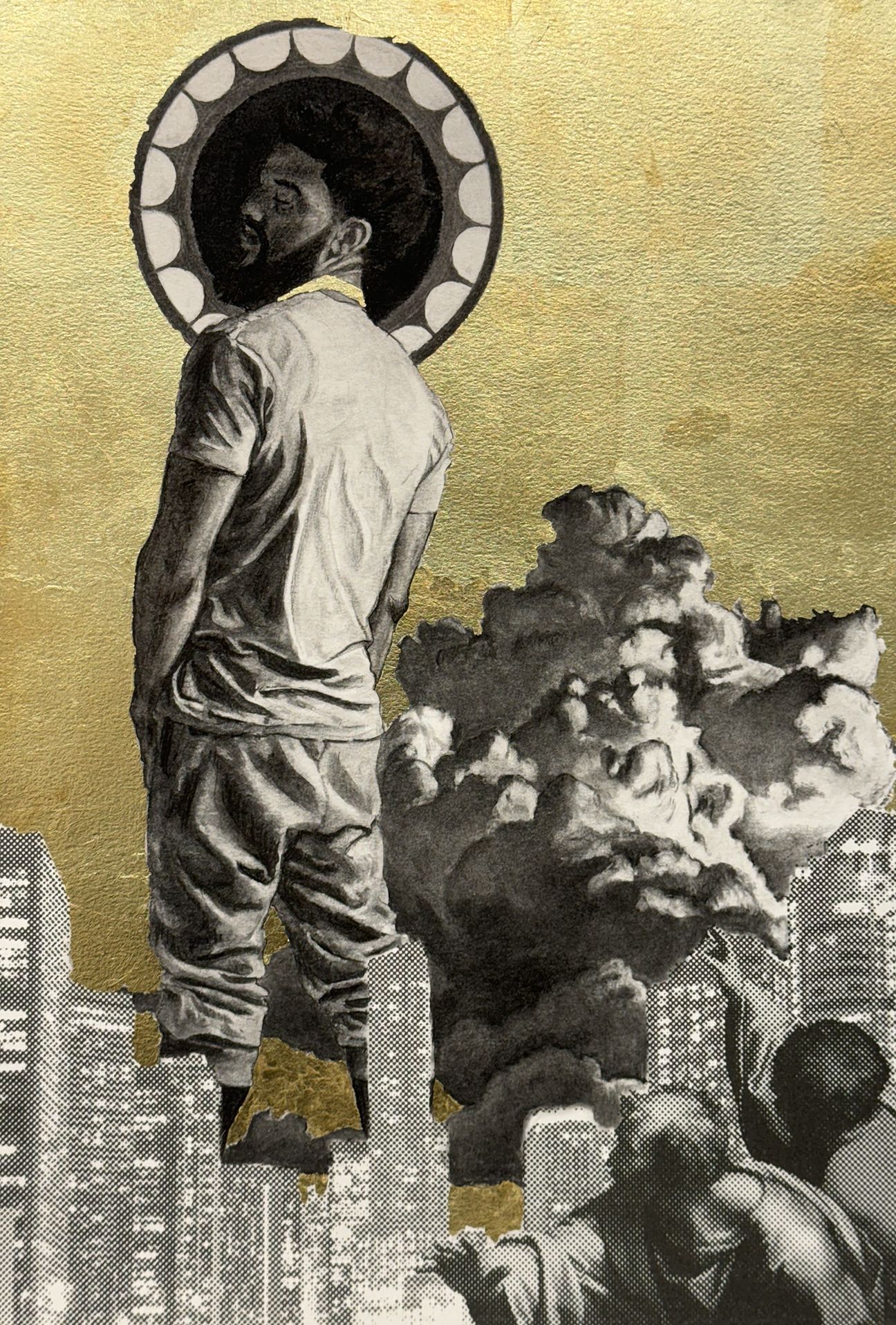

"The Audacity" mixed media installation by Michael Boyd Roman

"The Audacity" mixed media installation by Michael Boyd Roman

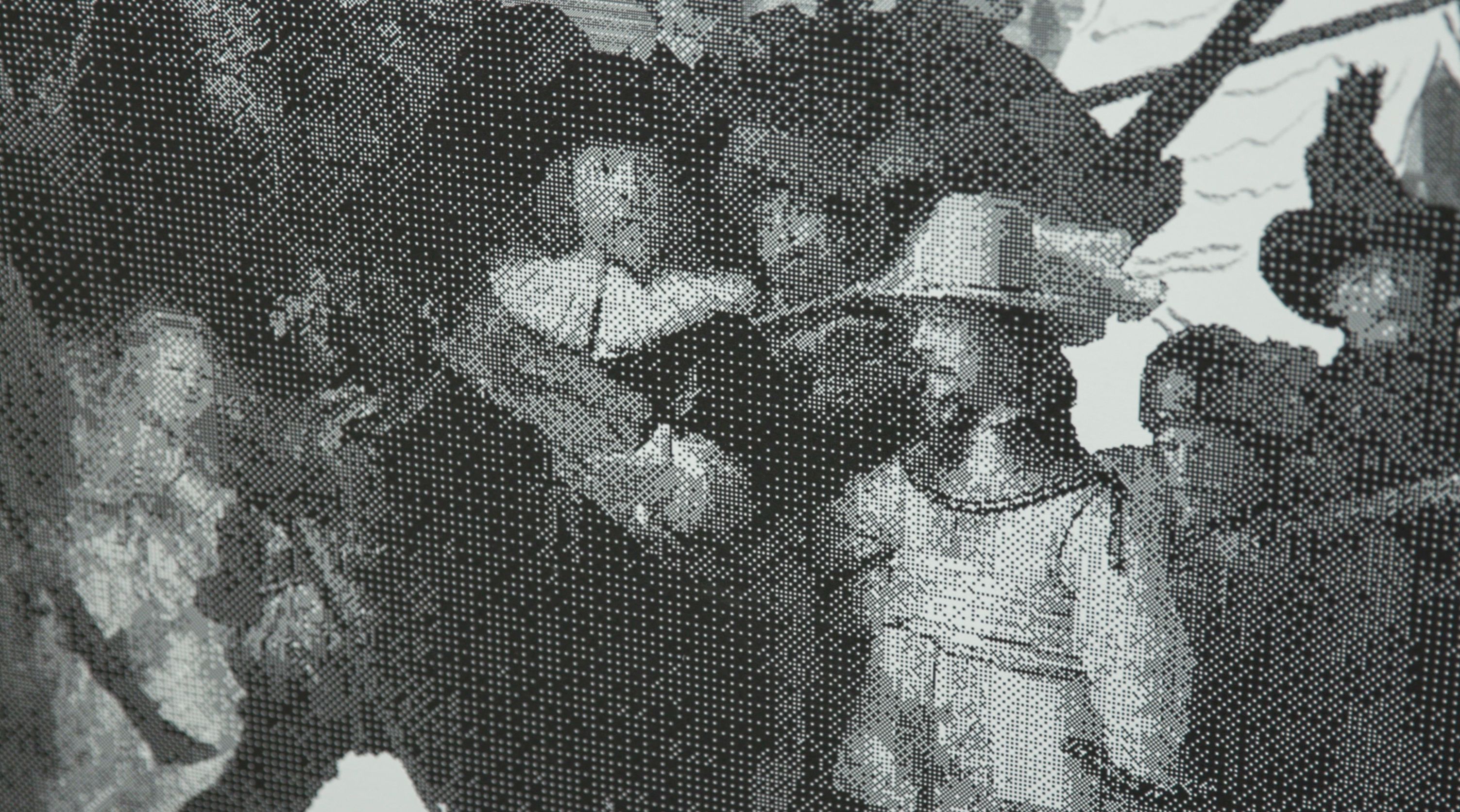

"The Pipeline" by Michael Boyd Roman

"The Pipeline" by Michael Boyd Roman

"Loiter Kings as Pantokrator" by Michael Boyd Roman

"Loiter Kings as Pantokrator" by Michael Boyd Roman

If Roman can speak to his college freshman-self, he feels young Black men will see themselves in his work, too.

“Once they start to ask questions, which hopefully they do, we get to a place of understanding, presence and purpose,” he said.

Roman's latest work features Negus, named for an Ethiopian word meaning “king” and popularized in recent years by rapper Kendrick Lamar. Negus is shown in a mosque in Gaza City, a painting of Saint Bartholomew during the Crusades and even in settings Cleveland and Washington, D.C. He's the smallest giant. functioning as a silent witness to the politics of our time.

“I am by no means a religious person in any way, shape or form,” he said. “To me, the idea that any one religion has it completely right and everyone else has it completely wrong - it's the height of human arrogance. And that said, most religions will say that. Their definition or version of God is everywhere and in everything. And if that's the case, then that concept of God or the divine is inside all of us as much as it is floating in the sky. If you truly believe that … how you treat people has to change. How you treat yourself has to change.”

When Roman became a father a decade ago, he took a step toward change by mending his relationship with his own father.

“I don't think I could have a relationship with him if we had not,” he said. “I was like, ‘Hey, I need to get to a place of understanding here, because… I'll be damned if our relationship, my son’s, mirrors your relationship with me.”

Roman said he was taken aback when his father started to laugh.

“He was like, ‘I said the same thing when you were born,’” he said. “At that moment, it kind of clicked that none of what happened between us was personal towards me.”

In adulthood, Roman said his parents have been two of the strongest supporters of his art. Yet, it’s not the recognition or the financial incentive which drives him to create.

“It's part of why I teach; part of why I work a job,” he said. “I don't want to be beholden to a market. I don't want a curator or a gallerist telling me that I have to make more of something, because that's what the market likes to see from me.”

In some ways, he’s not sure what drives him.

“If I knew the answer, then I probably wouldn't need to do it,” he said. “In other ways, it's as simple as: Because I have to. It's why I'm here.”