Beethoven, The Royal Philharmonic Society, and the Canon (Oh, My!)

Beethoven Symphonies in Great Britain

The 250th Anniversary

The year 2020 is a significant one for Beethoven: the 250th anniversary of his birthday in 1770. Although halted by the COVID-19 pandemic, countries all over the world had programmed concerts and presentations in honor of Beethoven’s 250th birthday.

The international legacy of this composer is massive, with monuments and busts erected to his image across the globe - from the small town of Bonn, Germany to New York City.

The Beethoven Monument, by sculptor Ernst Julius Hähnel (1811–1891), Bonn, Germany. (Photograph by Thomas Wolf)

The Beethoven Monument, by sculptor Ernst Julius Hähnel (1811–1891), Bonn, Germany. (Photograph by Thomas Wolf)

Ludwig van Beethoven memorial, by sculptor Henry Baerer (1837-1908), Central Park, New York City, New York, USA. (Photograph by Wikipedia user Daderot)

Ludwig van Beethoven memorial, by sculptor Henry Baerer (1837-1908), Central Park, New York City, New York, USA. (Photograph by Wikipedia user Daderot)

In Germany, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra organized a 24-hour Beethoven marathon. In China, the Xinghai Concert House and Guangzhou Opera House programmed a joint series of eighty of Beethoven’s “major works,” including symphonies, piano sonatas, and an opera. In London, Sir John Eliot Gardiner planned to lead the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique in sequentially performing all of Beethoven’s symphonies in only six days.

In light of this global celebration, many of us might wonder how a composer from a small town in Germany, who lived for less than sixty years, has maintained this international prestige.

As part of the 250th anniversary celebrations, London’s Royal Philharmonic Society intended to address that very thought with the lecture “Why Beethoven Matters.”

Why does Beethoven matter? And why does he matter so much in England, a country he never stepped foot in?

The Royal Philharmonic Society of London played an important role in advancing Beethoven's symphonies into the English repertory and canon. Scroll through this page to find out more about Beethoven's history in London!

As “Beethoven's most important institutional partner in England,” the Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) represents a long-standing connection between Beethoven and England.

The RPS has their own monument to Beethoven, the “Beethoven Bust,” which was first presented in 1870.

Professor F. Schaller's plaster bust of Beethoven, presented to the Society by Fanny Linzbauer. (Royal Philharmonic Society Archive: "Papers relating to the Society's links with Beethoven, and to Schaller's bust of the composer," p.90)

Professor F. Schaller's plaster bust of Beethoven, presented to the Society by Fanny Linzbauer. (Royal Philharmonic Society Archive: "Papers relating to the Society's links with Beethoven, and to Schaller's bust of the composer," p.90)

In their founding mission of programming great instrumental works of “genius,” not only did the RPS shift the direction of musical culture in England, but its history sheds light on the importance of both commissioning music and the idea of “works of genius” in maintaining the Beethoven canon that has pervaded popular culture even today.

Beethoven Symphonies in Great Britain (1803-1832)

“Of all the countries outside the Austrian empire, none took a greater interest in Beethoven than England.”

London, 1803: Beethoven was almost completely unknown.

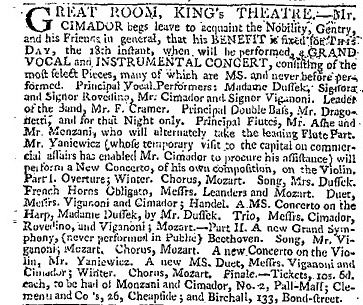

An advertisement in London’s Times newspaper writes of a “Grand Vocal and Instrumental Concert” on May 18th, 1803 at the Great Room in King’s Theatre. The ad notes “a new Grand Symphony, (never performed in Public), Beethoven.”

Excerpt of The Times newspaper from May 18, 1803, p. 1. (Gale Primary Sources)

Excerpt of The Times newspaper from May 18, 1803, p. 1. (Gale Primary Sources)

This advertisement is the only surviving indication of the first performance of a Beethoven symphony in London. Although the symphony is unnamed, since it would be a couple of years until programs began to include specific names of pieces, Nicholas Temperley posits that this piece was likely Beethoven’s Symphony No.1 in C Major, Op. 21.

The concert described in this ad is only one example of Great Britain's lively musical culture. British musical festivals could be found all over, such as the Norwich Festival which presented an unidentified Beethoven symphony in 1809. In London specifically, musical opportunity was provided through benefit concerts like the one advertised in The Times in 1803, royally sponsored concerts like the Ancient Concerts (1776-1848), or subscription-based concerts like the Vocal Concerts (1801-1821).

Yet, the regional British festivals programmed excerpts of various Beethoven symphonies more so than full works. Additionally, it is clear from extant programs and newspaper entries that at least from from 1803-1832, Beethoven works like the oratorio Christus am Ölberge were way more popular than the symphonies, with at least 17 performances at British musical festivals compared to Beethoven’s (by far) most popular symphonic work: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67, with 13 full performances. In London, the Vocal Concerts primarily focused on vocal music, and the Ancient Concerts were the only series to program symphonies but focused less on contemporary music.

Overall, most of these concert series were made up of vocal songs, virtuosic show pieces, and excerpts from larger works. And they were very long.

By 1812, Beethoven’s symphonies no. 1-6 had been premiered in Vienna, and according to Temperley, Beethoven’s symphonies no. 1-3 had likely been heard in London.

Interestingly, the relationship is inverted when it comes to the publication of engraved full scores, as the first of these occurred in London. The first editions of Beethoven’s symphonies were published in either Leipzig, Vienna, or Mainz, but usually only as a series of orchestral parts. While the engraved full scores of the first three symphonies were not published in Austria until 1816, or other Germanic regions until 1823; they are all first seen in London by early 1809.

Clearly, even before the Royal Philharmonic Society had its first concert in 1813, there was a demonstrated interest in Beethoven.

Beethoven and the Royal Philharmonic Society (1803-1832)

“Founded in 1813, the Royal Philharmonic Society is the oldest surviving public concert-giving body in the UK and the second oldest in Europe.”

The founding members of the RPS (John Baptist Cramer, Henry Dance, Philip Antony Corri, and Charles Neate) discussed starting this institution as early as January 24, 1813. Many of these men have demonstrated connections to Beethoven’s music.

Philip Antony Corri’s The Feast of Erin (a work for piano) was programmed on the same concert as an unidentified Beethoven symphony as part of the Norwich Festival in 1809, a festival which was largely overrun by George Friedrich Handel's works. Later at the Birmingham Musical Festival of 1826, an unidentified piano concerto by John Baptist Cramer would be programmed on the same night as Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, along with works by Henry Purcell, Gioachino Rossini, and Carl Maria von Weber.

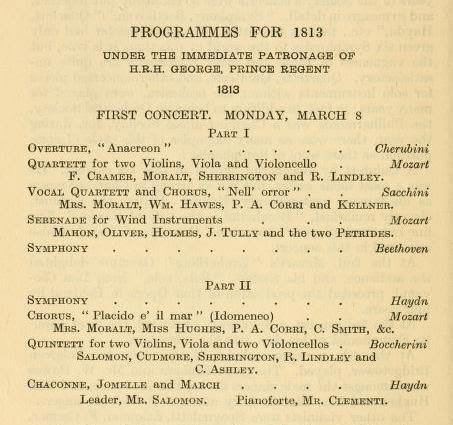

Less than two months after the founding members discussed initiating the Royal Philharmonic Society, its first concert took place in 1813. The program for the premiere shows that a "Symphony" by Beethoven concluded the first part of the concert. Not only does a Beethoven symphony appear on the RPS’ first concert, but works by Beethoven appear on every one of the eight concerts of this first season, three of these works being symphonies.

The Royal Philharmonic Society changed everything for the state of Beethoven in Great Britain, but particularly London. The Society was interested in actively commissioning new music, specifically “serious” symphonic and chamber works: “that species of music which called forth the efforts and displayed the genius of the greatest masters.” The Society’s mission was also significant in furthering symphonic development. In addition to focusing on “serious” instrumental works of genius, the Society sought to drastically improve orchestral sound. With no “genius” composer of their own, the Society sought to establish a firm connection with Beethoven. They wanted him to compose works for them, and then come to London as musical director of the works’ performances.

This interest in Beethoven as a "serious" composer of "genius," resulted in the rapid expansion of Beethoven works in the English repertory.

However, there would be tricky situations in the following years regarding the RPS' commissions of Beethoven's work.

In 1815, the Society commissioned Beethoven to write three original overtures, giving the RPS the right of first performance. Scholar David Warren Hadley, among others, has referred to this as the “Deception of 1815," because instead of acquiring newly composed works, the RPS received three overtures that had already been performed. These were Zur Namensfeier and the overtures to Ruins of Athens (a set of incidental pieces) and King Stephen (a commemorative work for Stephen I, the founder of Hungary). However, the word “deception” may be unwarranted as there is evidence suggesting that both Beethoven and the RPS were aware that the pieces had already seen their premiere.

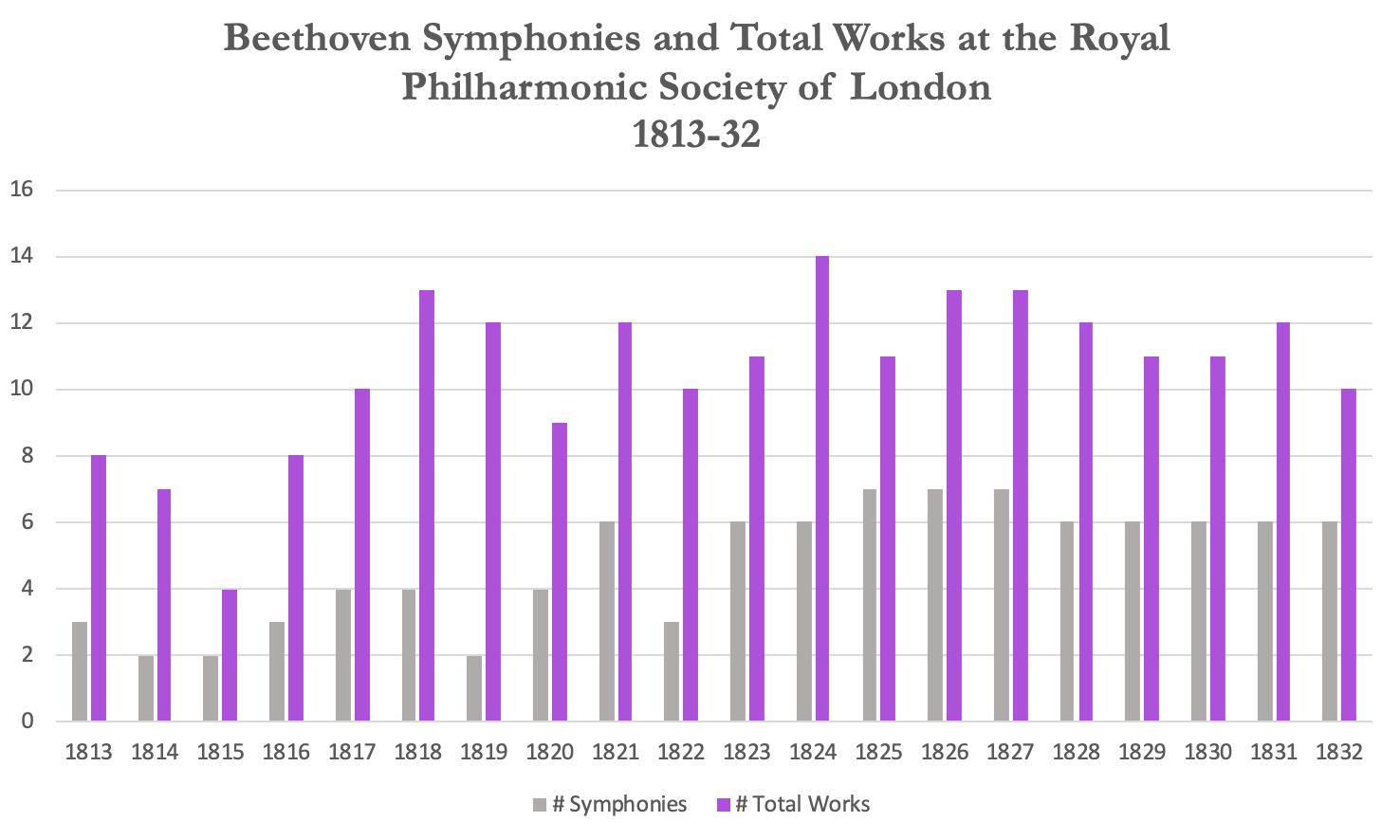

In any case, the number of Beethoven works continued to steadily increase. The graph below (compiled from seasonal program information from Myles B. Foster's History of the Philharmonic Society of London 1813-1912) illustrates this growth:

As Beethoven symphonies saw their British premieres, we begin to see interesting differences between the British and Germanic reception of these works.

Soon, the RPS would present the British premieres of Beethoven's symphonies nos. 5 and 7. Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92 would not be performed again at the Society until 1821, which may suggest it was not well received as it also posed a difficulty to interpreters in Vienna. Interestingly, this goes against Beethoven’s own opinion of the symphony given that in a letter he wrote to Johann Peter Salomon (RPS member, composer, violinist), he called it “one of my best works.”

Of the 40 concerts put on by the Society between 1818-1822, only 4 did not include works by Beethoven.

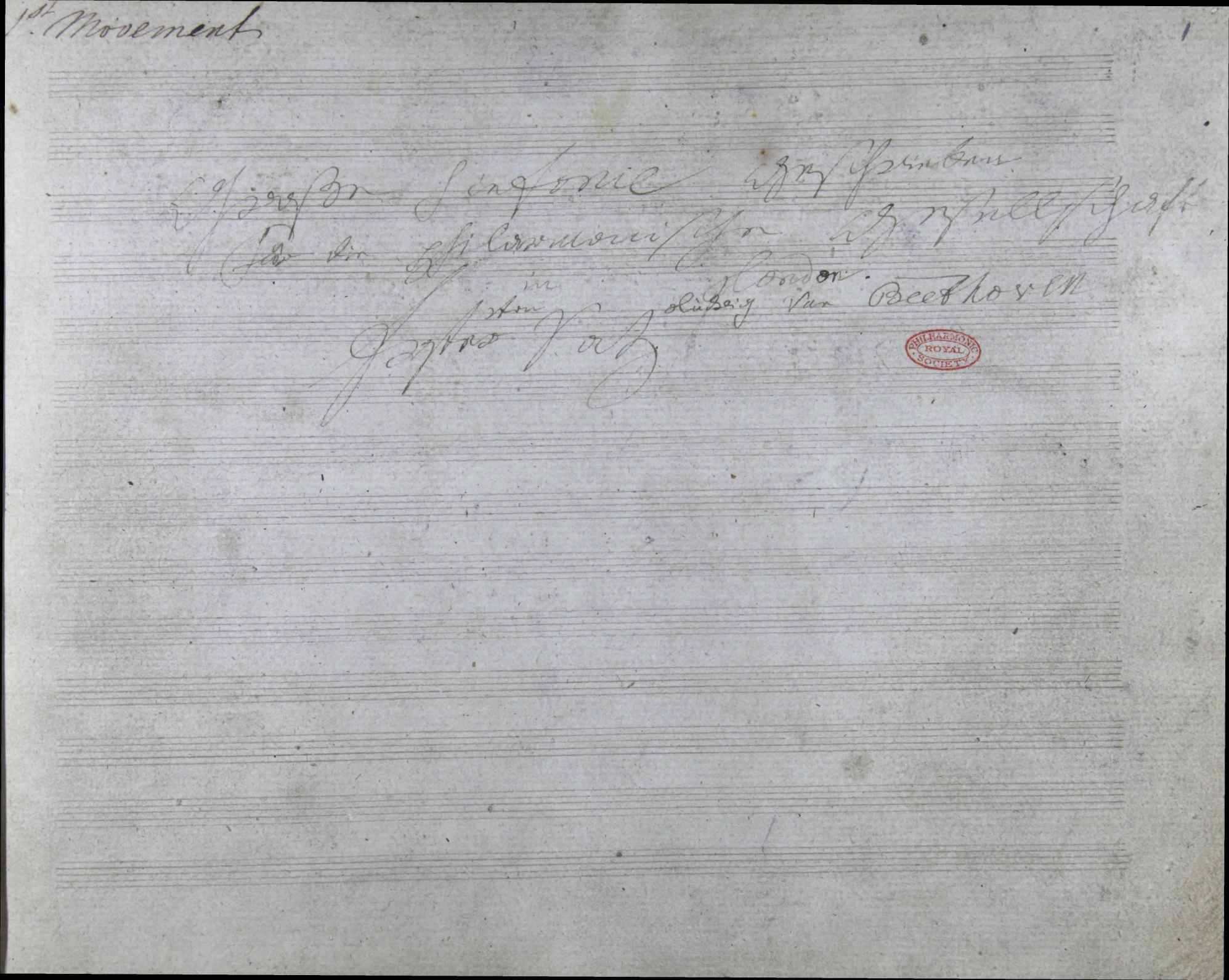

By 1822, after a few months of correspondence between the RPS and Beethoven which failed to bring Beethoven to London, the RPS offered £50 to commission a new symphony (Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125) to be performed in the 1824 season. However, the promised symphony was delayed and was unable to be performed during that season. Later in the same year, the RPS repeated their offer for the commission of the symphony and a visit to London. Unfortunately, Beethoven never made to London, an over 900-mile journey that would have included traveling across the English Channel. To make matters worse, Symphony No. 9 was premiered in Vienna in May of 1824, apparently against the terms of the agreement. The RPS performed the British premiere of Symphony No. 9 on March 21, 1825, under the director George Smart who had conducted numerous Beethoven symphonies at musical festivals across Great Britain. This concert was apparently the Society’s 116th performance of Beethoven works, and by this point they had presented all but Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93.

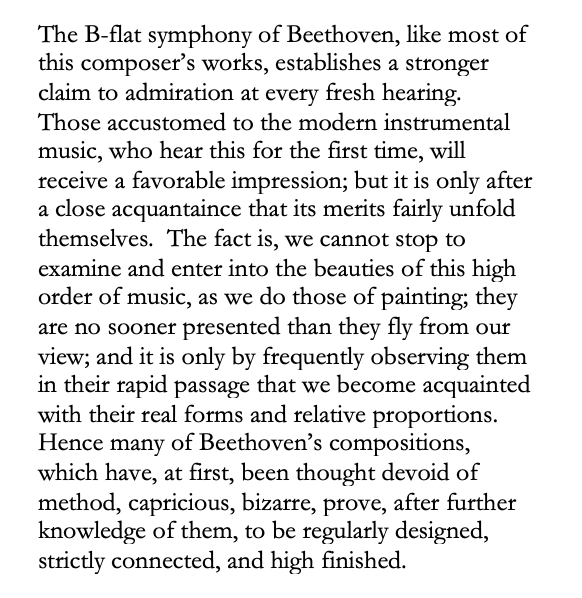

Between 1823-1832, Symphonies No. 4, 5, and 6 were among the most popular at RPS, as they were each performed every year of this decade. The Harmonicon, a significant London music magazine founded in 1823, wrote of Symphony No. 5: “if sublimity were [Beethoven’s] object in writing it, he attained it.” The Harmonicon described this symphony as a “chef-d’ouevre” in reviews from 1823, 1824, 1826, and 1831. The newspaper also wrote that Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 60 is a “fine and spirited composition,” and is “perennially hailed as one of Beethoven’s finest works.” Symphony No. 4 would go on to receive positive reviews from 1827-1831. The Harmonicon reviewed an RPS concert in 1830 and wrote:

Review of Beethoven's Symphony No. 4 at the Royal Philharmonic Society, reconstructed by me (The Harmonicon, vol. 8. London: Samuel Leigh, 1830, pp. 215-216)

Review of Beethoven's Symphony No. 4 at the Royal Philharmonic Society, reconstructed by me (The Harmonicon, vol. 8. London: Samuel Leigh, 1830, pp. 215-216)

Outside of England, Symphony No. 4 received mixed reviews.

According to Antony Hopkins, Carl Maria von Weber wrote: “First a slow movement full of disconnected ideas at the rate of three or four notes to each quarter-hour….to end with, a furious finale whose only requirement is that there should be no recognisable ideas but an abundance of changes of key — never mind modulating, just jump on to another note when you like!” (Antony Hopkins, The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981, p. 124.)

An entry in Allgemeine musikalische Zeitungreview from August 11, 1813 references the reception of the symphony in Milan, stating that the work “did not please at all."

It is clear that the RPS played an active role in commissioning and advancing Beethoven's works in London. This timeline summarizes some significant events within Beethoven's lifetime regarding performances and premieres of Beethoven's works at the Royal Philharmonic Society.

From 1833-1850, the Royal Philharmonic Society performed Beethoven’s symphonies twice as often as ones by Mozart or Haydn - a distinct change from the previous pattern of symphonic programming in Britain. The RPS faced many shortcomings due to issues with rehearsals and discord within its leadership, yet the Society was responsible for “some of the finest contemporary rendering of Beethoven” in the 19th century.

We know that the RPS’ interest in Beethoven is significant both in furthering Beethoven works into the British repertoire, as well as contributing to the increase in performances of symphonies as a genre in general. But the RPS is a great example of the importance of the relationship between musical institutions and composers in securing a composer’s place in the musical canon.

Program of the Royal Philharmonic Society's first concert on March 8, 1813 (Myles B. Foster, History of the Philharmonic Society of London 1813-1912, London: John Lane, The Bodley Head)

Program of the Royal Philharmonic Society's first concert on March 8, 1813 (Myles B. Foster, History of the Philharmonic Society of London 1813-1912, London: John Lane, The Bodley Head)

Map showing London and Vienna (A Comprehensive Atlas Geographical, Historical & Commercial by T. G. Bradford in The National Archives: Selected Maps Representing the Long 19th Century)

Map showing London and Vienna (A Comprehensive Atlas Geographical, Historical & Commercial by T. G. Bradford in The National Archives: Selected Maps Representing the Long 19th Century)

Copy of Symphony No.9 with dedication to the Royal Philharmonic Society of London (Royal Philharmonic Society Music Manuscripts: Manuscript Music from the Library of the Royal Philharmonic Society Nineteenth Century Collections Online)

Copy of Symphony No.9 with dedication to the Royal Philharmonic Society of London (Royal Philharmonic Society Music Manuscripts: Manuscript Music from the Library of the Royal Philharmonic Society Nineteenth Century Collections Online)

The Legacy of the Royal Philharmonic Society

Although the RPS faced many shortcomings due to issues with rehearsals and discord within its leadership, yet the Society was responsible for “some of the finest contemporary rendering of Beethoven” in the 19th century.

"The manner in which Art is handled nowadays is inexcusable. I have to pay one third of my receipts to the management and one fifth to the prison budget. The devil take it! Before it is all over, I shall be asking whether music is free Art or not."

Many composers were unhappy with relying solely on their benefactors or patrons. Although Beethoven maintained relationships with his patrons, Beethoven was one of the first composers to receive a commission from a musical institution.

This institution was the Royal Philharmonic Society, as they commissioned various orchestral works from Beethoven, the most significant being Symphony No. 9.

Lydia Goehr writes that musical works “required publishing houses, performing bodies, and a paying public to sustain their worldly existence.” Beethoven and the RPS relied on all of these kinds of contributors and participants. The initial mission of the RPS was to maintain a permanent symphony orchestra in London, form lucrative connections with composers of genius (specifically instrumental works), and “encourage an appreciation by the public in the art of music.”

Not only did the RPS financially support Beethoven through commissions, but the organization also sent money to Beethoven as he was dying.

Beethoven in the Canon

Beethoven’s symphonies have a strong place in the classical music repertory, and they carry with them a range of associations with the Beethoven “myth,” whether that be the trope of triumph over struggle, or characteristics of “heroism.”

Institutions like the RPS were interested in supporting new music; music created beyond associations with extra-musical organizations like the aristocracy. Thus, it is important to recognize the role of London musical life in the perpetuation of Beethoven in our present-day musical canon.

At the end of the day, we must acknowledge the organizations like the Royal Philharmonic Society, whose financial support and efforts to attune the public to “serious” instrumental works played an important role in the perseverance of Beethoven's music.

Plaque of the first UK performance of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 by the Royal Philharmonic, Regent Street, London (Wikimedia Commons)

Plaque of the first UK performance of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 by the Royal Philharmonic, Regent Street, London (Wikimedia Commons)