The Headwaters

Fighting to keep the upper Cuyahoga River pristine

by Mark Urycki

The very beginnings of the East Branch of the Cuyahoga in some woods near Montville in Geauga County. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

The very beginnings of the East Branch of the Cuyahoga in some woods near Montville in Geauga County. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

The treed corridor helps filter the water and its shade provides an important cooling effect for fish and other wildlife. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

The treed corridor helps filter the water and its shade provides an important cooling effect for fish and other wildlife. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

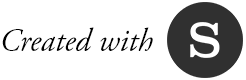

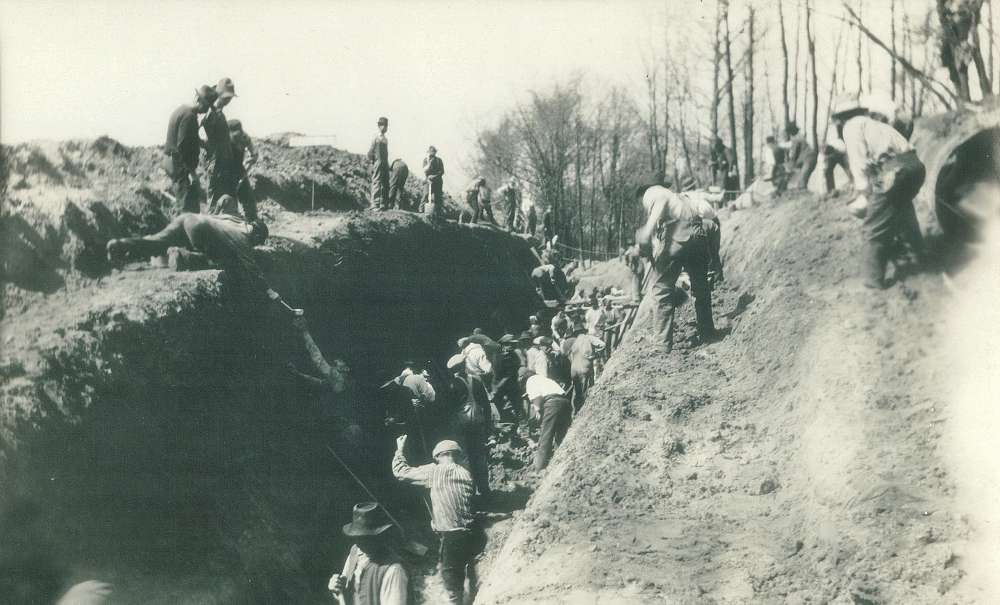

Workers dig water transmission main trench, circa 1912. [City of Akron]

Workers dig water transmission main trench, circa 1912. [City of Akron]

The very beginnings of the East Branch of the Cuyahoga in some woods near Montville in Geauga County. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

At mile 100 in the woods of Geauga County, northeast of Chardon, small rivulets of water trickle south, joining other rivulets to form the headwaters of the Cuyahoga River.

The source is rain and melting snow.

“We’re in the snow belt here and so that means not only more snow but more rain,” said naturalist Dan Best of the Geauga Park District. “A higher amount of precipitation, I think, than anywhere else in the state of Ohio.”

The glacial geology of this area helps filter this water as it seeps into the soil and percolates down.

Listen to ideastream's Mark Urycki report about keeping the headwaters clean.

“The sandstone has a lot of connected little space between sand grains,” Best explained. “So it’s not only porous it’s permeable. That means those little pores are connected and water is able to move down into aquifers, and it’s a water supply.”

The treed corridor helps filter the water and its shade provides an important cooling effect for fish and other wildlife. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

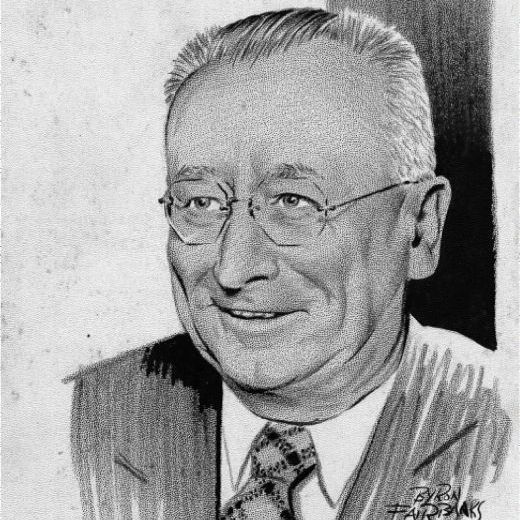

Akron officials recognized that a century ago. The city established its first municipal water system around 1910 and looked to the Cuyahoga River for fresh, clean water.

Waterworks manager Wendell LaDue built the city’s reservoir, Lake Rockwell, in Kent. But then he did something unusual - buying up land along the river to protect it.

Akron’s Watershed Superintendent Jessica Glowczewski considers him a visionary, although he had to battle the doubters.

“Trying to convince Akron City Council, Akron residents that, ‘Yeah, we should buy land in Portage County and then way up in Geauga County, like, 50 miles away. This is in your best interest,’” Glowczewski explained.

During the Great Depression, LaDue was able to use public works money to put people to work. The city built two backup reservoirs in Geauga County and bought land along the river to buffer any runoff.

Workers dig water transmission main trench, circa 1912. [City of Akron]

“Wetlands along the main stem along any tributaries into the Cuyahoga River,” said Glowczewski. “Those are the kinds of properties LaDue was interested in and the city ultimately became interested in purchasing and protecting and preserving those lands.”

Today the largest landowner in Geauga County is the city of Akron.

Some city of Akron land close to its water reservoir, Lake Rockwell, is highly restricted. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

Some city of Akron land close to its water reservoir, Lake Rockwell, is highly restricted. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

ideastream’s in-depth local reporting is made possible by donations from supporters like you.

Join us as a Member now.

ideastream.org/donate

A Prehistoric World

The river here is a different river than what flows through Cleveland 100 miles downstream.

“There’s this Cuyahoga River that is the headwaters part that Akron owns, that’s 15 miles of completely undisturbed flood plain and river systems that's completely natural,” said Brett Rodstrom of the Western Reserve Land Conservancy.

In fact, shortly after the infamous 1969 river fire in the shipping channel, the state studied the upper Cuyahoga and in 1974 designated that section a Scenic River.

“There are dozens and dozens of endangered species that live there, ” said Rodstrom. “It’s an unbelievable resource. It’s probably the best example of an intact ecosystem in Northeast Ohio.”

Today, you can still paddle for miles and miles and see no sign of humans. No homes, no buildings, no roads.

Matthew Smith, Assistant Regional Scenic River Manager for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, says it’s like going back in time, and the wildlife here reflect that, like the rare Sandhill Crane.

“When you hear them call they sound like this prehistoric creature calling out and it’s very loud. It’s an incredible thing to hear.”

There are also bald eagles, ospreys, otters, an occasional black bear and fish. Smith credits the land preservation along the riverbanks for the clean water and habitat.

A beaver at the water's edge. [Kendra Becker / Camp Hi]

A beaver at water's edge. [Kendra Becker / Camp Hi]

“It’s a testament to how, if you have these lands that are forested - the buffering capability that they have - to provide that clean water for many people,” said Smith.

That’s been good for business for Kendra Becker’s family in Hiram. Her parents started the Camp Hi Canoe and Kayak Livery in the 1960’s.

“We believe this is the jewel of Northeast Ohio, this river,” said Becker. “And it’s a fantastic asset to our community and our area to have this so close to Cleveland. And as the upper end of the Cuyahoga it’s a great example of what was and what could come back.”

For those who live and play on the healthy upper Cuyahoga, they hope it stays that way.

Protecting the Headwaters

Buckeye Partners LP petroleum storage and pipeline on the east bank of the Cuyahoga River in Mantua. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

The upper portion of the Cuyahoga isn’t just pretty, it’s the source of drinking water for 280,000 households served by the city of Akron.

Just eight miles upstream of Akron’s water reservoir is a petroleum facility on the banks of the river. Akron’s Watershed Supervisor Jessica Glowczewski keeps an eye on it.

“They still have issues with the materials that spilled, leaching out from the soils into the river,” she said. “We monitor their discharge points and we monitor the river through that section.”

In September, the company, Buckeye Partners L.P., spilled 8,000 gallons of jet fuel into a river in Indiana. But Kurt Princic of the Ohio EPA is more sanguine about the danger of the Mantua site.

“There are engineering controls in place,” said Princic. “They have to have secondary containment if it does get to the river.

“Can I guarantee you nothing is going to happen? No, but we do have engineering controls in place.”

Other potential threats to the river and the drinking water are less noticeable. Sand and gravel pits in the watershed dig down to the water table and thus could affect the groundwater.

A waste-water injection well near the river drills through the groundwater layer to pump in brine and chemicals.

But Brett Rodstrom of the Western Reserve Land Conservancy feels the controls on those are pretty good.

Rain runoff from streets, parking lots, or farms can also add contaminants to the river. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

“If things broke there would be problems, but they’ve been well maintained. They were put in correctly,” said Rodstrom. “It’s a threat. It certainly didn’t improve anything in those areas but to the point that people try to make it, ‘This is going to ruin the water quality of these counties,’ it hasn’t yet. And as long they’re maintained properly and installed properly it shouldn’t.”

“You know, it’s a lot cheaper to maintain high-quality systems than it is to restore them.”

As bad as an oil spill sounds, it could be worse. Jessica Glowczewski says it’s actually easier to clean up oil because it floats. But a spill from say, a milk truck, would be a bacterial nightmare.

“We worry about highways,” Glowczwski said. “You know, there are a couple of different highways that go across waterways in the watershed and what could those tanker trucks be carrying? Anything.”

The more likely threats to the pristine headwaters of the Cuyahoga are more mundane.

“A lot of these areas are pretty rural so you have septic systems on all of them. And unfortunately, with septic systems, they’re underground. So when they fail nobody notices,” said Glowczewski.

But Dan Best of the Geauga County Park District does.

“You can drive the county roads,” said Best, “and you’ll see people’s septic - little drainage pipes. After the septic systems have done their jobs you get the outflow into roadside ditches and they work their way into streams.”

Akron recently bought an old trailer park whose wastewater system was failing and dumping sewage into a stream.

Akron recently bought this derelict trailer park to prevent its failing wastewater system from polluting the river. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

Buckeye Partners LP petroleum storage and pipeline on the east bank of the Cuyahoga River in Mantua. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

Buckeye Partners LP petroleum storage and pipeline on the east bank of the Cuyahoga River in Mantua. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

Rain runoff from streets, parking lots, or farms can also add contaminants to the river. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

Rain runoff from streets, parking lots, or farms can also add contaminants to the river. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

Akron recently bought this derelict trailer park to prevent its failing wastewater system from polluting the river. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

Akron recently bought this derelict trailer park to prevent its failing wastewater system from polluting the river. [Mark Urycki / ideastream]

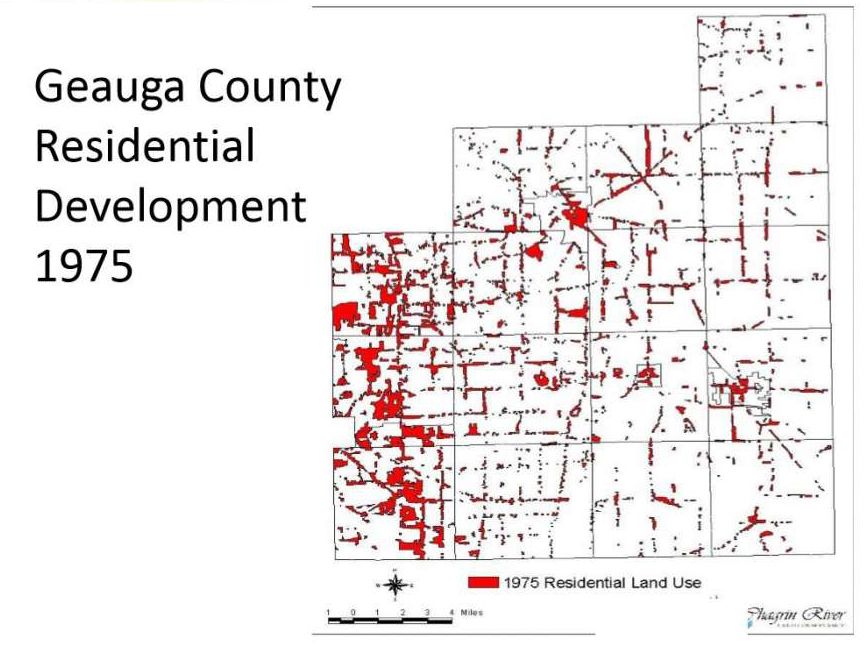

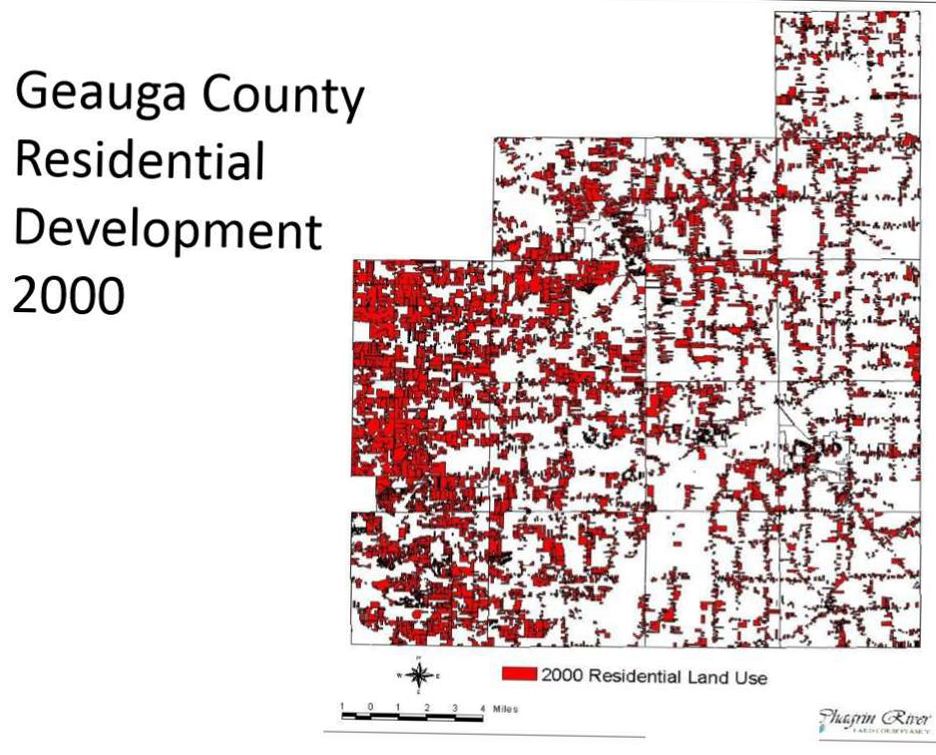

An impact more difficult to stop is urban sprawl. People and businesses in the western parts of Geauga and Portage counties are moving east around the river.

So rain hitting all that new concrete washes oil and road salt into the river. It also washes manure and fertilizer from farm fields.

The Ohio Department of Natural Resources fears the loss of important wooded buffers between people and the river.

The Messenger Farm protected by the Western Reserve Land Conservancy. [Dee & Bill Belew}

The Messenger Farm protected by the Western Reserve Land Conservancy. [Dee & Bill Belew}

The ODNR’s Matt Smith says development is the reason why they’ve been purchasing conservation easements along the riverbanks.

“We don’t own the land. The landowner still owns the land, but we purchase some of the development rights of those properties,” Smith explained. “And the purpose of that is to maintain the buffer areas along the river system and along some of the streams.”

It's Cheaper To Maintain Than To Restore

The Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Ohio EPA, the City of Akron, county park districts, and even the Cleveland Museum of Natural History are working to protect the river’s headwaters. So are private citizens.

Dee Belew and her husband Bill bought the 200-year-old Messenger Farm in Auburn almost three decades ago. They don’t want it broken up into housing development.

“And we could have been millionaires overnight, but the money was not the issue with us. It was the land,” Belew said.

Bill & Dee Belew at the Messenger Farm in Auburn.

Bill & Dee Belew at the Messenger Farm in Auburn.

Their property is surrounded on three sides by the Auburn Marsh. The Belews still own the land and can sell it, but they worked with the Western Reserve Land Conservancy to place restrictions on how the land can be used after they’re gone.

“Auburn had lots of farms and a lot of them were developed,” said Belew. “So it’s just nice to be part of one chunk of land that’s going to stay that way forever.”

The 200-year-old Messenger Farm in Auburn. [Bill & Dee Belew]

The 200-year-old Messenger Farm in Auburn. [Bill & Dee Belew]

One saying goes, the Cuyahoga is 100 miles long and 30 miles from beginning to end. As the crow flies, the headwaters are just 30 miles from the industrial flats so the cautionary tale is understood.

“It’s so much more economically reasonable to protect it before it’s broken, than try to fix it on the back end,” said Rodstrom.

And Matthew Smith adds, “You know, it’s a lot cheaper to maintain high-quality systems than it is to restore them.”

That’s a lesson learned after 50 years of restoring the lower Cuyahoga River.