The Million-Dollar Dump

How the operators of an East Cleveland dump collected millions in public money.

by Nick Castele

April 22, 2019

Updated July 11, 2019

In March 2018, workers carted away the final remains of a mountain of demolition debris from a 9.9-acre former industrial site in East Cleveland.

For nearly three years, neighbors on Noble Road had watched as the pile at Arco Recycling grew bigger and bigger, finally covering more than five football fields and rising higher than their homes.

“Living beside this has been more than just a nightmare,” one neighbor, Willie Morrow, told ideastream in early 2017. “There’s no peace no more. You can’t sleep, you wake up all hours of the night, morning, you hear all the noise coming from the trucks. It’s bad.”

Even after cleanup finally began in July 2017, the indignities continued. The debris heap caught fire that fall and burned for days.

The cleanup cost Ohio taxpayers $9.1 million. But that’s not the only way the public was caught up with the dump.

An examination of contracts, court filings and other records shows that public dollars and public agencies enabled the mess that was Arco Recycling.

East Cleveland sold Arco the land for half its county-estimated market value.

The people accused of running the dump secured $4 million in public funding through the Cuyahoga Land Bank to demolish around 480 properties in the Cleveland area. Debris from more than 330 of those demolitions ended up at Arco, which the Cuyahoga County Board of Health later declared a public nuisance.

The Ohio EPA monitored the site, but maintains it did not have the legal authority at the time to regulate debris recyclers.

At the center of all this was a demolition contractor with a record of financial crimes who, for nearly three years, navigated the holes and silos in the system.

George Michael Riley Sr. [Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction]

George Michael Riley Sr. [Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction]

A lawsuit by the Ohio Attorney General’s Office accuses George Michael Riley Sr. of operating the dump. Riley was also involved with three demolition companies that contracted with the land bank, records show. Two of the three companies disposed at Arco, according to the land bank.

Riley began working with the land bank while still on supervised release from prison, Licking County court records show. Years earlier, he had pleaded guilty to charges in state and federal court after prosecutors accused him of lying to financial institutions.

Although multiple public bodies knew of Arco, the dump was allowed to operate from the spring of 2014 until the Ohio EPA shut it down in January 2017.

“This really fell into a regulatory gray area,” Diane Bickett, the director of the Cuyahoga County Solid Waste District, said in an interview. “And Mike Riley took advantage of these loopholes.”

Bickett said she raised concerns about the site in 2015 to the land bank and Ohio EPA.

“This site showed all the signs of a sham facility that was going to take in material, claim to be recycling it, make money off of having the material dumped there, and pocket the money and then abandon the site,” Bickett said. “We knew, day one, the minute we saw the site.”

ideastream’s in-depth local reporting is made possible by donations from supporters like you.

Join us as a Member now.

ideastream.org/donate

Firefighters control a blaze inside the Arco Recycling debris pile in late 2017. Cleveland's public health department included this photo in a presentation about the dump. [Cleveland Department of Public Health]

Firefighters control a blaze inside the Arco Recycling debris pile in late 2017. Cleveland's public health department included this photo in a presentation about the dump. [Cleveland Department of Public Health]

Federal dollars underwrote most of the land bank demolitions performed by the three companies connected to Riley. Funding largely came from the U.S. Treasury Department’s Hardest Hit Fund, according to the Cuyahoga Land Bank, a quasi-governmental agency that demolishes abandoned properties and prepares land for redevelopment.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Ohio used the Hardest Hit Fund to clean up blight and help people stay in their homes. Cuyahoga County also paid to raze dozens of properties that ended up at Arco, according to a list obtained from county council.

And that meant taxpayers effectively helped subsidize a public nuisance in a city hit hard by the very rash of foreclosures that the government was trying to soothe.

“This site showed all the signs of a sham facility that was going to take in material, claim to be recycling it, make money off of having the material dumped there, and pocket the money and then abandon the site.”

One of the demolition companies that dumped at Arco, RCI Services, has since caught the attention of the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

Last year, federal prosecutors named RCI Services in the indictment of former land bank employee Kenneth Tyson. Prosecutors accused Tyson of accepting $6,700 in work at his property paid for by RCI Services and a contractor identified as “M.R.” In exchange, the indictment alleges, Tyson helped put RCI Services on the land bank’s list of qualified demolition contractors.

Riley, who often goes by Mike, was not charged in the indictment, nor did prosecutors mention Arco Recycling. But last month, the state attorney general’s office added RCI Services as a defendant in the civil suit, alleging that Riley operated the company. Riley is listed in RCI contracts as the company’s vice president of operations.

This building stands at the address listed for RCI Services and Red Rock Services in Ohio EPA documents included with Cuyahoga Land Bank contracts. The property is now in tax foreclosure. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

This building stands at the address listed for RCI Services and Red Rock Services in Ohio EPA documents included with Cuyahoga Land Bank contracts. The property is now in tax foreclosure. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

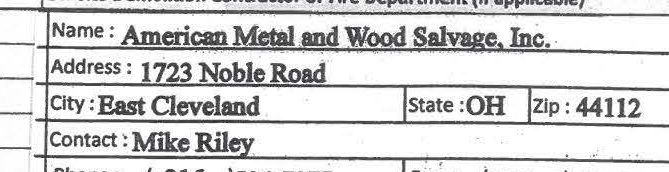

After RCI Services, Riley was involved with a second land bank contractor called American Metal and Wood Salvage, according to land bank contracts. Bankruptcy records list Christina Beynon as the owner of both AMW Salvage and Arco Recycling. She is also a defendant in the attorney general’s lawsuit.

In total, RCI Services and AMW Salvage received about $3 million to knock down more than 360 structures, taking rubble from most properties to Arco, according to land bank records.

Beynon’s attorney, Anthony DeGirolamo, wrote in an email that his client did not want to discuss Arco. Asked about AMW Salvage, DeGirolamo replied that Beynon had “no active involvement in the operation of the business.”

In excerpts from a 2017 video obtained by ideastream, Riley discusses the demolition company Red Rock Services.

In excerpts from a 2017 video obtained by ideastream, Riley discusses the demolition company Red Rock Services.

Records show that Riley later ran a third demolition company, Red Rock Services LTD., which received about $1 million from the land bank. It did not take debris to Arco.

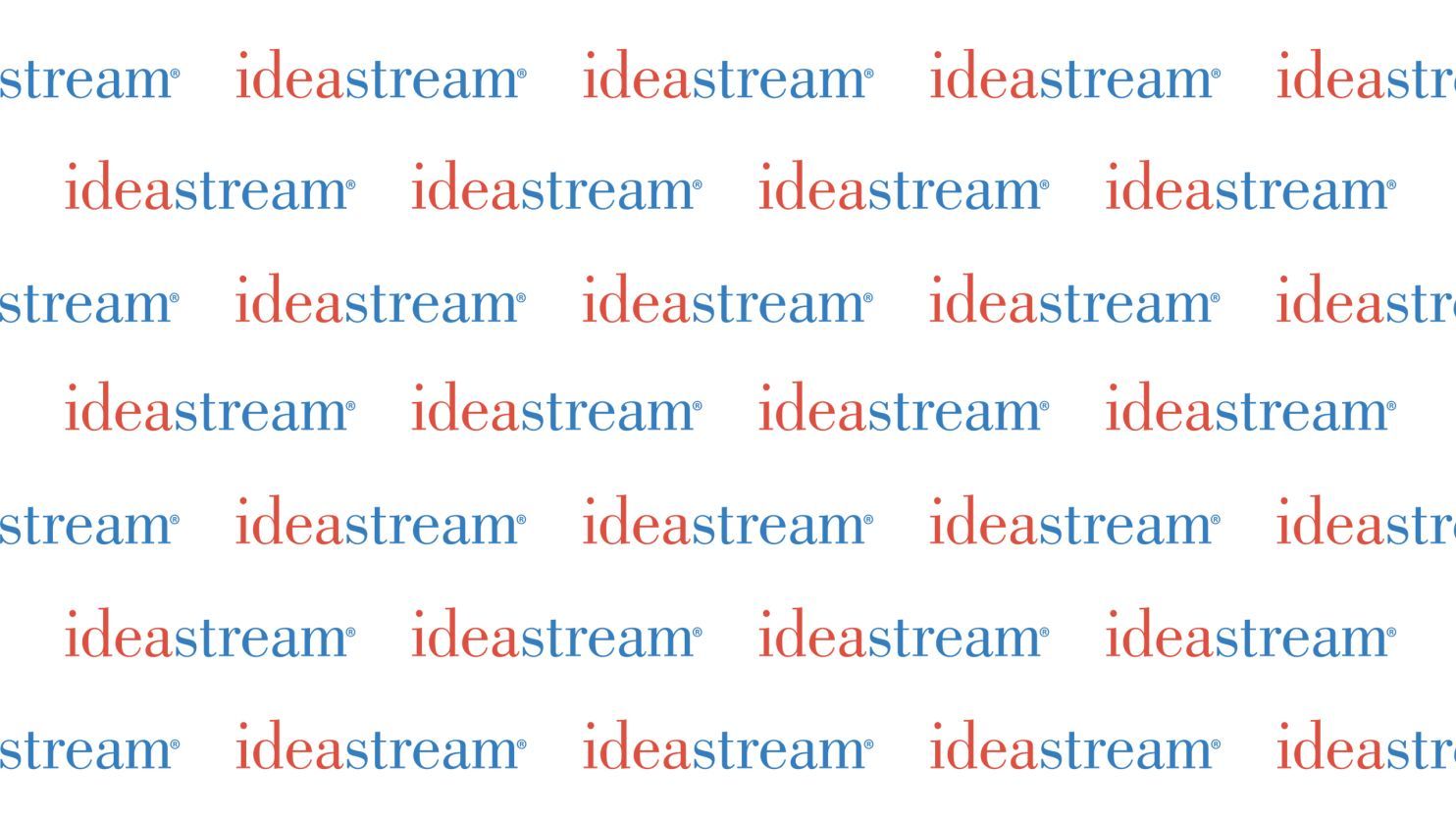

Riley was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, and turns 56 this year. He appears to have returned to the eastern Ohio area, opening a business in Steubenville in 2017. In April last year, he changed his name to Anthony Michael Castello in Jefferson County Probate Court.

When approached in person before a January court hearing, Riley declined to answer questions about Arco, RCI Services or AMW Salvage. His attorney, who was about to withdraw as Riley’s counsel, said Riley did not own Arco and had been fired from the company. Riley did not respond to follow-up questions sent by certified mail to an address listed for him in county court records.

George Michael Riley changed his name last year to Anthony Michael Castello. [Jefferson County Probate Court]

George Michael Riley changed his name last year to Anthony Michael Castello. [Jefferson County Probate Court]

Riley’s attorney wrote in a 2017 court filing that his client had left Arco by the time of the shutdown order.

“The OEPA changed the regulatory nature of the material and of the Arco site months after Riley was no longer involved as an employee of Arco and after, upon information and belief, the Arco business failed,” the court filing reads, “which occurred months after Riley was [sic] no longer worked at the site or otherwise was involved in any fashion with the site.”

“Ohio EPA observed a substantial increase in the amount of construction and demolition debris at the Facility. Currently, the construction and demolition debris at the Facility is estimated to be six hundred (600) feet long by five hundred (500) feet wide and reaching approximately fifty (50) feet in height. ”

Heidi Griesmer, a spokeswoman for the Ohio EPA, said that Riley departed from Arco in the summer of 2016. She said the agency tried to work with Beynon.

“She expressed interest in doing the right thing, and we provided her information about best practices,” Griesmer said. “We gave them tips for how they could further improve their operations by bringing in additional employees to process more waste, so they could reduce the amount of waste in the piles.”

But by January 2017, Arco still wasn’t recycling.

“We made the determination that they were operating as an illegal, open dump,” Griesmer said.

Officials examine the Arco site in 2017. [Cuyahoga County Board of Health]

Officials examine the Arco site in 2017. [Cuyahoga County Board of Health]

Gus Frangos, the land bank’s president, told a Cuyahoga County Council committee in 2017 that land bank demolitions made up only a small share of the debris at Arco.

Frangos responded by email this year to ideastream’s questions about Arco. He wrote that the three companies connected to Riley lived up to the land bank’s requirements, such as having proper equipment, experience, insurance and licensing.

“RCI, AMW, and Red Rock, like all demolition contractors interested in working for the Land Bank, completed all reviews and pre-qualification forms prior to being invited to bid and being awarded contracts,” Frangos wrote.

Cuyahoga Land Bank President Gus Frangos answers questions about Arco Recycling at a 2017 Cuyahoga County Council committee meeting. [Cuyahoga County Council]

Frangos wrote that the land bank requires contractors to take debris to licensed or legally permitted disposal sites. Contractors must provide dump receipts before the land bank will pay them, he wrote.

“Prior to January 2017, the Arco Recycling facility was being monitored by Ohio EPA and was authorized to accept debris for recycling,” he wrote. “Once we received notice from OEPA in January that they had shut down the Arco site, we advised all contractors that they could no longer take debris there.”

Frangos also wrote that the land bank was unaware of Riley’s criminal history and does not “engage in moral arbitration” of contractors’ pasts.

“In hiring demolition contractors, if someone is licensed, and qualified to do the job, the Land Bank cannot make moral judgments about a person’s criminal history especially if the person has served a sentence or is authorized to work,” he wrote. “Moreover, we subject ourselves to lawsuits when we begin summarily discriminating against contractors who are objectively qualified.”

The land bank provided copies of bids, contracts and payment amounts in response to public records requests.

The Arco site is now clean, but the legal fallout continues.

The Ohio Attorney General’s Office is in court trying to recoup cleanup costs. The federal criminal case involving the former land bank employee is ongoing. Noble Road neighbors won a $2.1 million default judgment against Arco late last year. And several local firms have sued Arco and the demolition contractors, saying the companies stiffed them on thousands of dollars in contracts.

Guilty Pleas And Prison Time

Prosecutors in Licking County obtained a 14-count indictment against contractor George Michael Riley Sr. in 2007. They accused him of grand theft and defrauding creditors, among other offenses.

Kenneth Oswalt, then an assistant prosecutor in the county, alleged in the bill of particulars that Riley orchestrated a number of financial schemes:

Oswalt wrote that Riley lied about his then-girlfriend’s assets and income to obtain home financing from Manhattan Mortgage, concealing the fact that he would be the true property owner.

Oswalt wrote that Riley fraudulently obtained several vehicles from a Licking County auto dealer, falsely claiming that he had power-of-attorney and that his father made $22,000 per month.

“The whereabouts of at least one of these vehicles,” Oswalt wrote, “remains unknown even today.”

Oswalt also accused Riley of using an ailing man’s name and good credit to secure financing for a 2001 Monaco La Palma RV.

“The defendant is alleged to have engaged in a series of fraudulent transactions that may appear on their face to be legitimate business transactions, but instead consisted of obtaining sums of money, financing, services and/or property based upon false or misleading representations.”

Riley would put property in the names of other people and companies so that creditors couldn’t trace it back to him, Oswalt wrote.

“This permitted the defendant to present himself to others as living at a higher standard of living than he could legitimately afford without these fraudulent transactions,” Oswalt wrote.

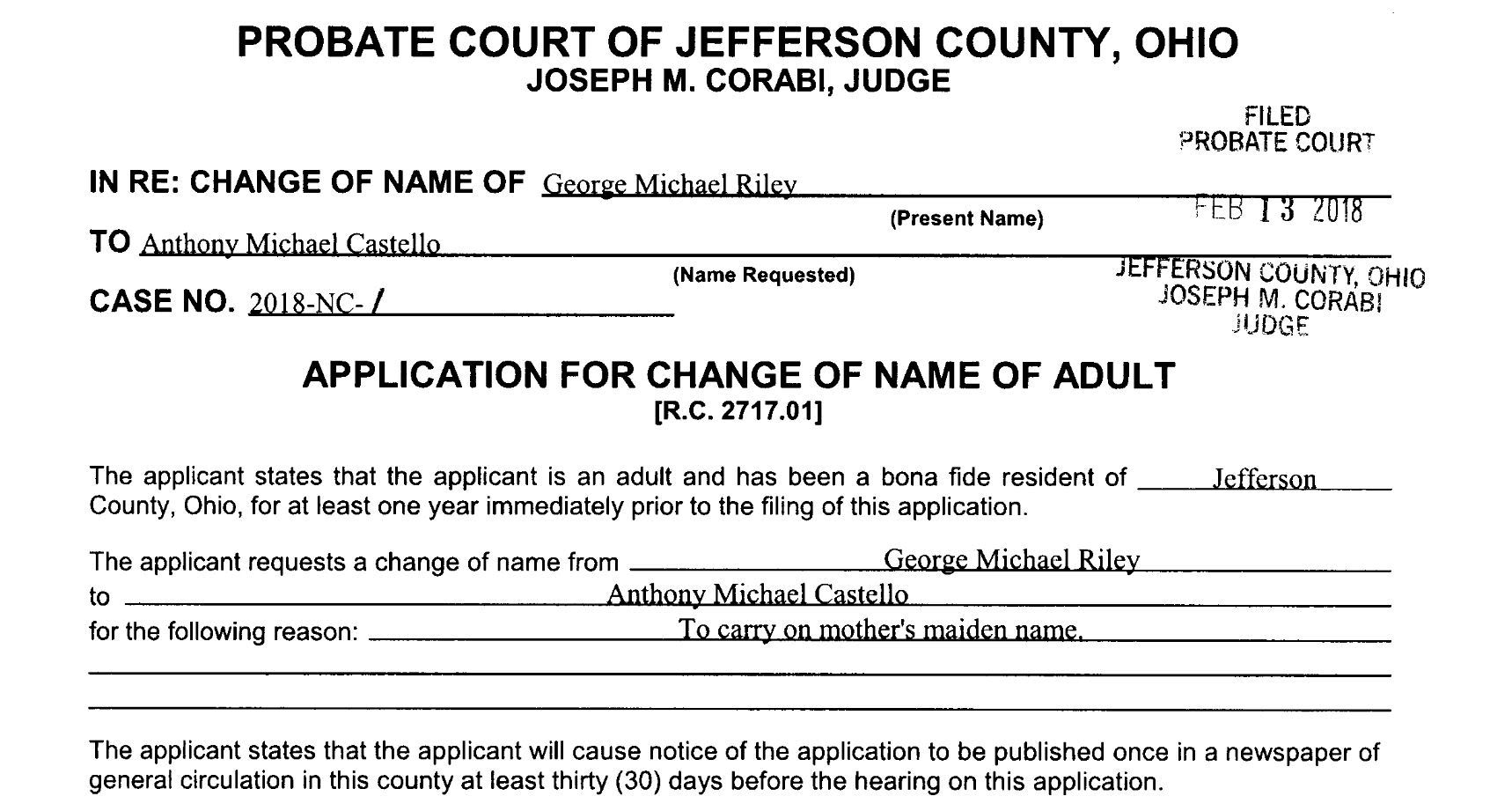

Riley pleaded guilty in federal court to using loans from Commodore Bank to buy this house in Hebron, Ohio, despite telling the bank that he would spend the money on equipment. [Google Earth]

Riley pleaded guilty in federal court to using loans from Commodore Bank to buy this house in Hebron, Ohio, despite telling the bank that he would spend the money on equipment. [Google Earth]

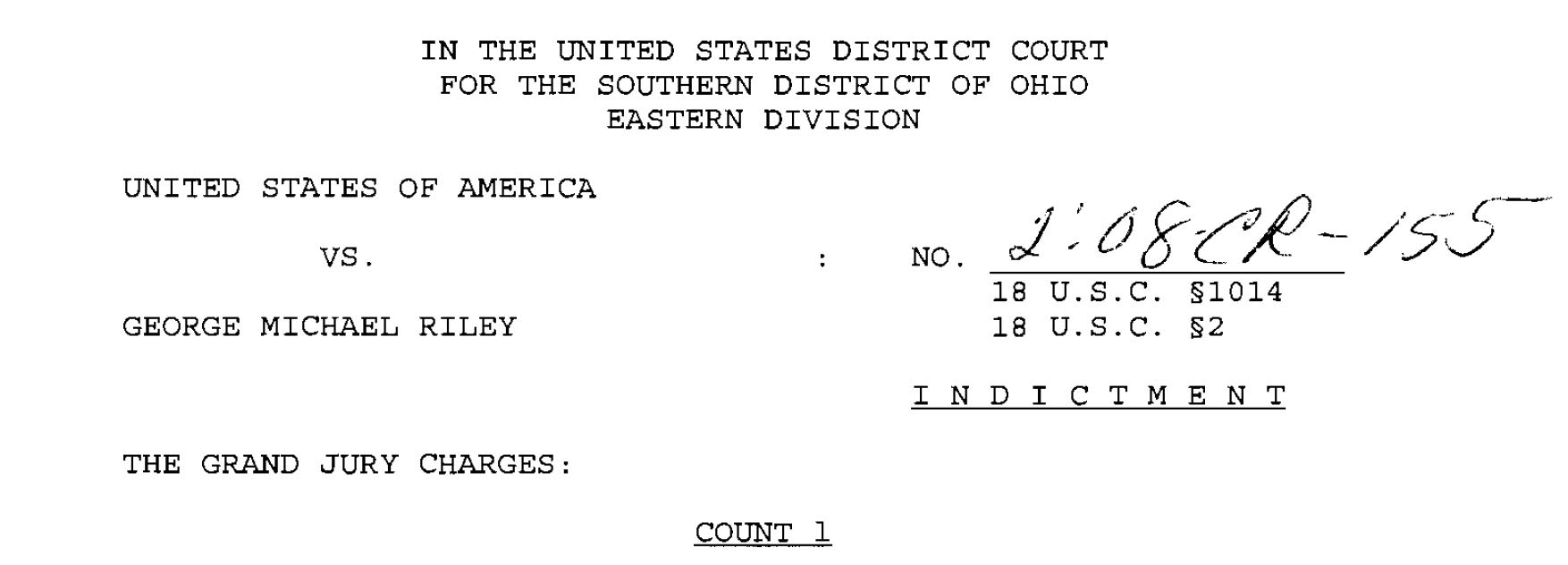

In 2008, a federal grand jury indicted Riley on charges of lying on a loan application.

Prosecutors alleged that Riley took out about $547,000 in loans from Commodore Bank, a lender based in central Ohio, to buy contracting equipment. Instead, the indictment said, Riley used the money to buy a house at Buckeye Lake.

Riley pleaded guilty in both cases. In 2008, a Licking County judge sentenced him to four years, 11 months in prison. The state took him to Chillicothe Correctional Institution, a prison in south-central Ohio. He also served his federal sentence there.

A federal grand jury indicted Riley in 2008. [U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio]

A federal grand jury indicted Riley in 2008. [U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio]

These weren’t Riley’s only criminal cases around that time.

In August 2007, he pleaded guilty to theft in Eagle County, Colorado, and paid more than $509,000 in restitution, according to court records.

In December of that year, Riley pleaded guilty in Franklin County to a charge of unauthorized use of property, according to court records. Prosecutors had accused him of accessing state tax records in 2005 to locate a witness, according to an article in the Newark Advocate.

Years later, when Riley sought in summer 2014 to terminate his period of supervised release from prison, a federal prosecutor cited his “terrible criminal record” in a brief opposing his bid.

“His criminal record includes numerous crimes involving deception and dishonesty,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Gary L. Spartis wrote. “That fact does not instill confidence that he will continue to be law abiding, or, even continue to follow the rules of his supervision.”

By then, Riley had been performing land bank demolitions in Cleveland for months.

After Prison, A New Attempt At Demolition

Riley won early release in April 2011, less than three years after entering prison. He went to work razing properties in Wheeling, according to a trove of business documents and depositions submitted into the record in federal bankruptcy court.

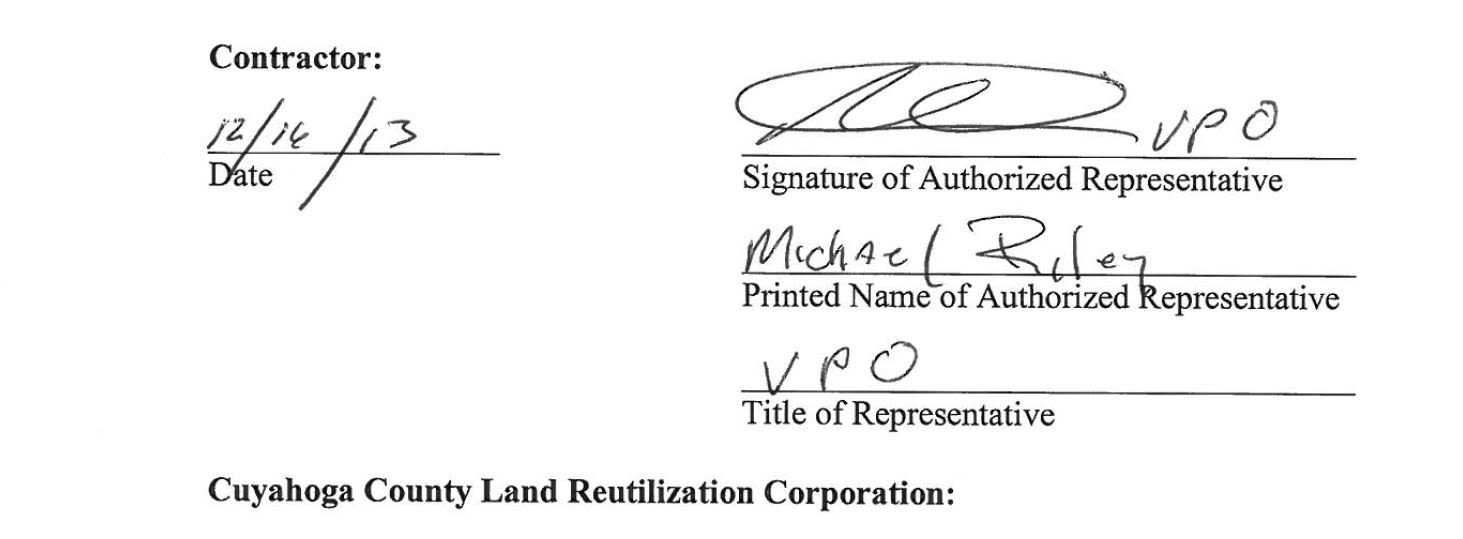

The following year, in 2012, Riley filed for bankruptcy. In a sworn bankruptcy court document dated Dec. 27, 2012, he included two companies on a list of personal property: United Waste Services Inc. and Residential, Commercial & Industrial Services LLC.

RCI Services formed in Massachusetts in May 2012 and was registered in Ohio the following year under the name Residential Commercial Industrial Services LLC, according to business records in both states.

But Riley’s name does not appear on those business formation documents. Ohio and Massachusetts business records listed LaTasha Atteberry as RCI Services’ manager and point of contact. She did not respond to requests for comment.

George Michael Riley Sr. included Residential, Commercial & Industrial Services LLC on a list of personal property in a bankruptcy court filing. [U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Ohio]

George Michael Riley Sr. included Residential, Commercial & Industrial Services LLC on a list of personal property in a bankruptcy court filing. [U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Ohio]

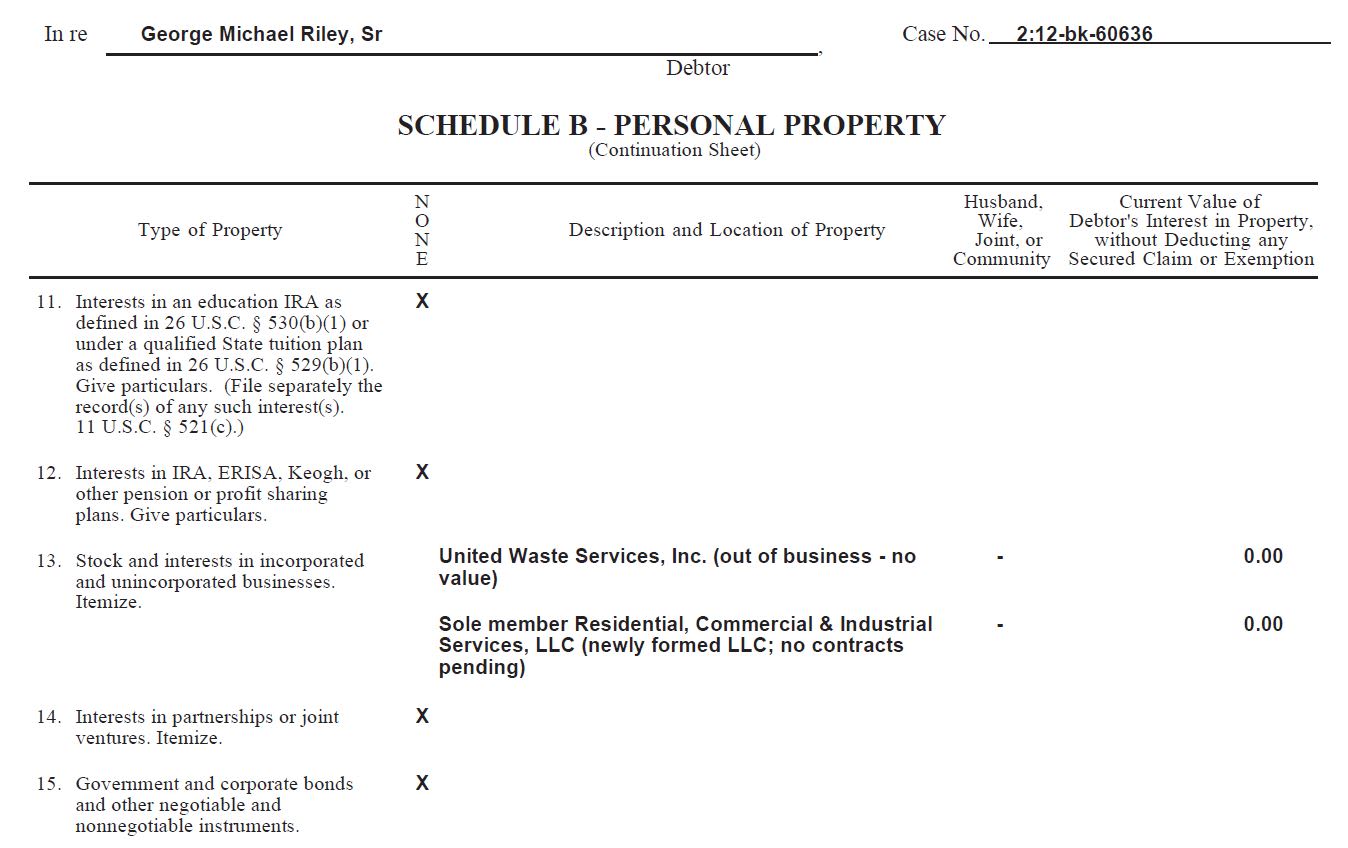

In a 2013 deposition, Riley denied owning RCI Services. Commodore Bank, one of the lenders Riley pleaded guilty to deceiving, pursued him in bankruptcy court and questioned him about his business dealings.

“What is RCI Services, LLC?” a Commodore attorney asked Riley in the November 2013 deposition, according to a transcript.

“I don’t know,” Riley said.

He did acknowledge that his signature appeared on an application for a demolition permit submitted by RCI Services in Wheeling. But Riley said he didn’t remember whether he performed the work.

“Are you an officer in RCI Services?” the attorney asked later in the deposition.

“Officer of what?” Riley replied.

“Of the company,” the attorney answered.

“I don’t understand what you mean,” Riley said.

“Do you hold any position with RCI Services, LLC?” the attorney pressed.

“She’s my friend,” Riley replied, apparently referring to Atteberry.

“Do you own it?” the attorney asked.

“I do not,” Riley said.

“Who owns it?” the attorney asked.

“I don’t know,” Riley replied.

A Commodore Bank attorney grilled Riley about his business dealings in a November 2013 deposition. [U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Ohio]

A Commodore Bank attorney grilled Riley about his business dealings in a November 2013 deposition. [U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Ohio]

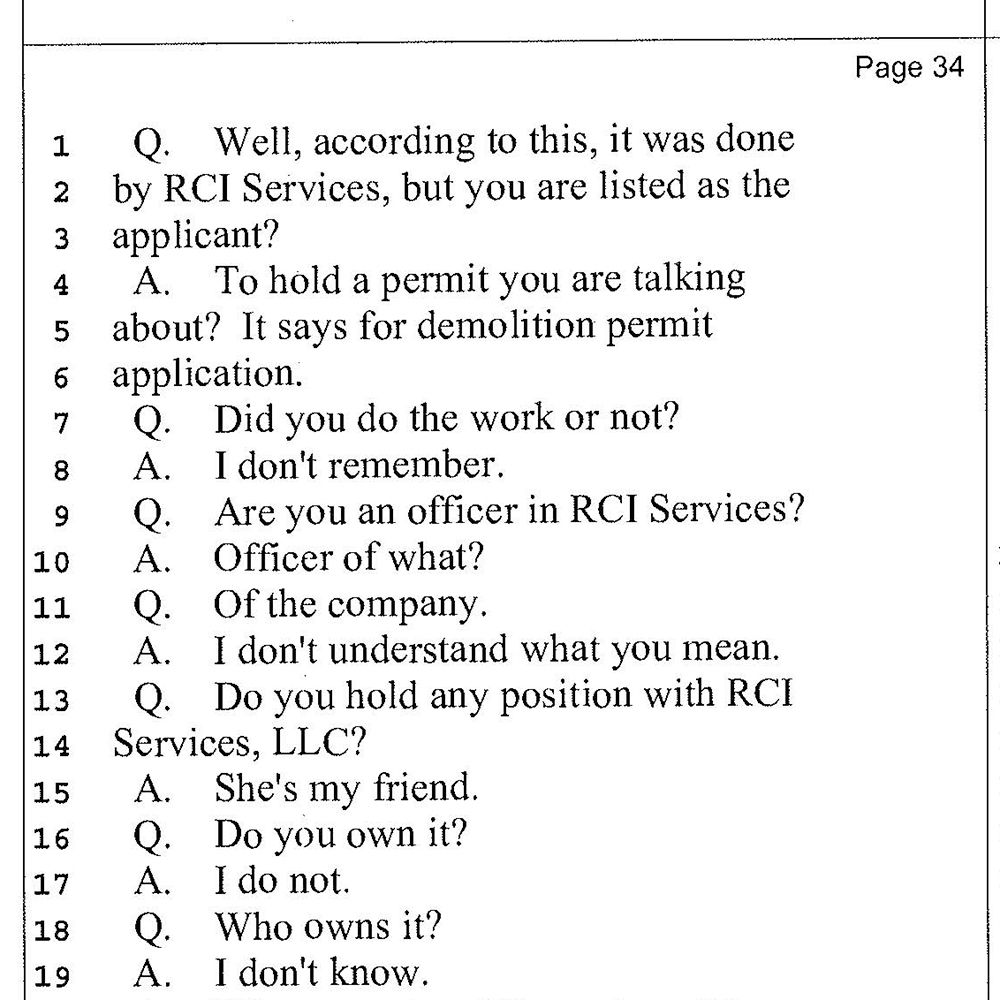

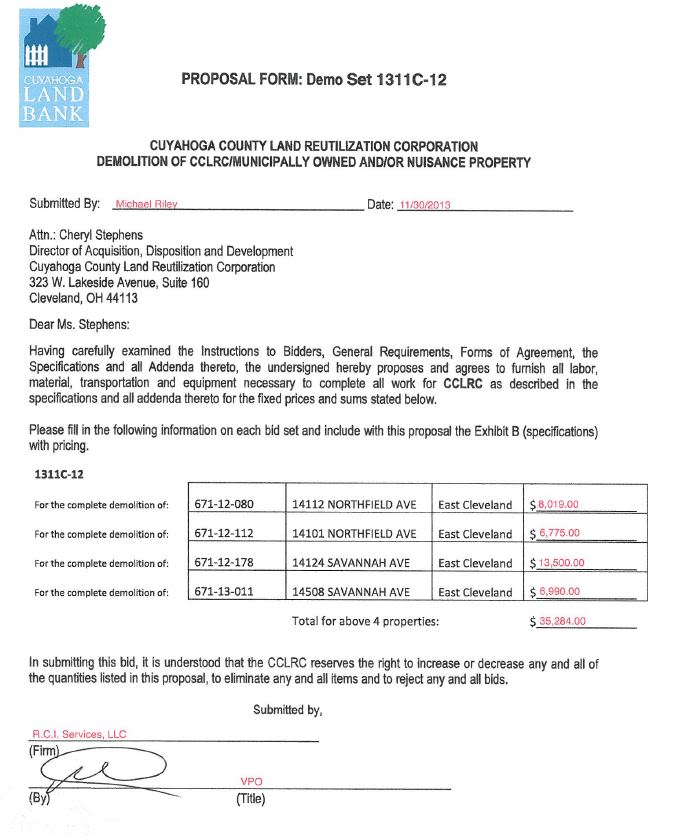

Several weeks after the deposition, RCI Services submitted its first bid for Cuyahoga Land Bank demolition work, contracts show.

RCI’s contract with the land bank was signed by Michael Riley, who is listed as the company’s “VPO.” Riley is listed as both RCI’s “pres” and “vice pres of operations” in December 2013 business documents submitted in Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court as part of a lawsuit.

The Carl B. Stokes U.S. Courthouse in downtown Cleveland. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

The Carl B. Stokes U.S. Courthouse in downtown Cleveland. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

Last year’s federal indictment accuses a then-employee of the Cuyahoga Land Bank, Kenneth Tyson, of helping RCI Services get a spot on the land bank’s list of qualified demolition contractors in late 2013.

In exchange, the indictment alleges, Tyson received work on his property—paid for by RCI Services and its operator, who is identified in the indictment as “M.R.” The indictment alleges that East Cleveland’s chief of staff, identified as “M.S.”, introduced M.R. to Tyson.

Michael Smedley, chief of staff to East Cleveland mayors Gary Norton and Brandon King, did not respond to requests for comment.

Tyson has pleaded not guilty, and the case is ongoing. His attorney declined to comment.

RCI Services' first bid for Cuyahoga Land Bank work. This contract is mentioned in last year's federal indictment of a former land bank employee. [Cuyahoga Land Bank]

RCI Services' first bid for Cuyahoga Land Bank work. This contract is mentioned in last year's federal indictment of a former land bank employee. [Cuyahoga Land Bank]

The indictment alleges that Tyson, M.R. and RCI Services tried to conceal their dealings from the land bank, law enforcement and the public.

“Whatever was alleged in the indictment, whether true or not, was external to the Land Bank,” president Gus Frangos wrote to ideastream. “No Land Bank systems were breached or defrauded.”

Cheryl Stephens, a former land bank official who now serves on Cuyahoga County Council, said the city of East Cleveland first brought Riley to the land bank’s attention.

Two land bank staffers visited Riley’s business site and concluded that he had the equipment necessary to do demolition work, Stephens said. According to the indictment, one of those staffers was Tyson.

“With that confirmation and information from the city of East Cleveland that they had completed correctly demolition work for them, they were allowed to attend our continuing education sessions that talked about what we wanted to see in the field,” Stephens said.

RCI Services began demolishing properties for the land bank, taking debris from most jobs to a new site in East Cleveland, records show.

The site was Arco Recycling.

A Dump Grows In East Cleveland

East Cleveland has spent most of the last three decades in state-declared fiscal emergency. In early 2014, the small city faced a general fund deficit of more than $3.2 million, according to state financial documents from the time.

The city sold off assets and cut staff. In March 2014, East Cleveland City Council passed legislation that proposed to sell a plot of city-owned land on Noble Road to Ohio Rock LLC or its designee. The company would improve the land, the ordinance said, by “remediating environmental matters” and “preparing the property for development.”

The 430,911-square-foot site once served as headquarters for Spero Electric, a light fixture manufacturer. Spero bought the property from General Electric in 1990 and moved out in 2005. East Cleveland’s land bank took over in 2012.

“So that is even better than a sheriff’s sale. We owned the asset and we sold the asset for $125,000...That will hit our books as new revenues and I believe that as soon as we get the check. And we will have a business functioning where the land had been dormant for 20 years.”

The city sold the land for $125,000 in May 2014 to 1705 Noble Road Properties LLC, property records show. Christina Beynon later disclosed in bankruptcy court that she owned 1705 Noble Road.

The price was less than the property’s estimated market value of $250,000, according to county records. But the city considered it another step in its plan to recover from fiscal emergency.

The old GE building was demolished, and the land on Noble Road began filling with debris. According to land bank records, RCI Services may have taken rubble to the site as early as April 2014. Material can be seen scattered at Arco in a Google Earth satellite photo dated June 14, 2014.

Satellite photos of Arco Recycling over time. [Google Earth]

Satellite photos of Arco Recycling over time. [Google Earth]

Through the rest of 2014 and the first half of 2015, RCI Services razed more than 130 county land bank properties, taking material from more than 115 of those demolitions to Arco, according to agency records. RCI Services received about $920,000, according to the land bank.

RCI Services hit a snag at the end of June 2015. The Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth’s office, which oversees business registrations, dissolved the company for failing to file annual reports.

In July, RCI Services submitted bids as usual to demolish land bank properties. But the land bank issued demolition go-ahead orders to a different company: American Metal and Wood Salvage Inc., which Beynon owned.

“RCI was allowed to assign its winning bids to AMW after RCI indicated to the Land Bank that it was no longer interested in doing the demolitions,” the land bank’s Gus Frangos wrote to ideastream.

Riley's name appears on an Ohio EPA document included with AMW Salvage's land bank contract. [Cuyahoga Land Bank]

Riley's name appears on an Ohio EPA document included with AMW Salvage's land bank contract. [Cuyahoga Land Bank]

After that, it was AMW Salvage that bid on land bank properties, demolished them and took most to Arco Recycling. The company knocked down around 230 properties and received about $2 million from the land bank, according to the agency’s records.

Ohio EPA documents included with the contracts list Mike Riley as the contact for RCI Services and AMW Salvage. Riley is also named as Arco’s operations manager on a 2015 business plan obtained from the county board of health. Documents from all three companies list the same cell phone number alongside Riley’s name.

A mound of debris rises above a garage on Noble Road in 2017. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

A mound of debris rises above a garage on Noble Road in 2017. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

Cheryl Stephens, the county council member and former land bank official, said that Riley regularly made low bids for demolition work.

As the pile of rubble at Arco Recycling grew, Noble Road neighbors and local activists raised the alarm. News outlets aired stories about Arco.

“What the neighbors wanted was a cease-and-desist and then a cleanup,” Stephens said. “I’m not arguing with the neighbors. But the reality is that while the land bank did do business with this company, we did not have the authority to shut them down.”

Stephens said it was the state of Ohio, not the land bank, that had authorized Arco.

Arco existed in an area of legal ambiguity. At the time, Ohio law didn’t regulate construction and demolition debris recycling.

“As long as they could make some demonstration that they were making efforts to recycle the material, we didn’t have the authority,” the Ohio EPA’s Heidi Griesmer said. “If they were not sending anything off site, not processing anything, then we had the authority to declare it as an open dump.”

Arco did have to comply with air quality regulations, though.

The Cleveland Division of Air Quality cited 1705 Noble Road Properties in June 2014, requiring Arco to get Ohio EPA permits for the site’s roads and storage piles. The permits, which Arco obtained later that summer, mandated that the company reduce the amount of dust floating off the property.

The division also cited Arco in 2015 for record-keeping violations, failing to clean paved roads and other problems. The company later resolved these issues.

A house across Noble Road from the Arco Recycling site. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

A house across Noble Road from the Arco Recycling site. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

In 2015, the Cuyahoga County Solid Waste District, a local agency that serves as a resource on trash and recycling, complained about Arco. So did U.S. Rep. Marcia Fudge, who wrote a letter to the Ohio EPA.

At the time, Cuyahoga County was developing rules for a $50 million demolition program. The county planned to give out money to cities and the land bank to raze vacant houses.

The solid waste district’s Diane Bickett and the head of the Environmental Crimes Task Force, a city and county law enforcement effort, met with Stephens in March 2015, according to a solid waste district timeline obtained by a public records request.

They asked the land bank not to allow disposal at Arco, but were told that the facility had the necessary permits, according to the timeline.

“The land bank, point blank, said, well, it’s the cheapest location, we’re going to take material there,” Bickett said.

Asked about this meeting, Stephens said she wanted to make the most out of limited taxpayer money. While the county did write new rules for recyclers, she said Arco was able to meet those standards.

“They didn’t create criteria that Arco didn’t comply with,” Stephens said. “If you don’t want to do business with someone, you need to create criteria that causes them to fall out of the hopper.”

Bickett said that Arco paid a small fee to begin a national recycling certification process, keeping just on the right side of the county’s minimum standards.

“As long as they could make some demonstration that they were making efforts to recycle the material, we didn’t have the authority. If they were not sending anything off site, not processing anything, then we had the authority to declare it as an open dump.”

Bickett said the waste district and task force wanted to search the pile of debris. If investigators could find forms of garbage classified as “solid waste,” such as household trash or food waste, then they could have legal grounds to shut Arco down or prosecute the operators, she said.

The Environmental Crimes Task Force talked with a county prosecutor about obtaining a search warrant for the Arco site in 2015, according to a Cleveland police spokeswoman.

But in May of that year, the Ohio EPA declined to participate in a search. The agency and county board of health had recently visited the site, Griesmer said, and they hadn’t found any solid waste.

“They did not feel that we had a strong enough case to prove that there was solid waste on site,” Bickett said. “But you don’t know until you go in there and excavate the pile and see what you can see. It would have been helpful to do that early on.”

The pile of debris at Arco Recycling in 2017. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

The pile of debris at Arco Recycling in 2017. [Nick Castele / ideastream]

More than 10 months passed. In April 2016, Ohio EPA staff made a surprise visit to the site. They reviewed Arco’s books, finding that an average of 11 percent of the debris, at most, had been recycled over the last year.

“We understand that Arco initially stockpiled a large amount of [debris] prior to beginning actual recycling operations and has made some strides in obtaining the equipment and personnel needed to recycle legitimate material,” Ohio EPA environmental specialist Bill Lutz wrote in a letter addressed to Michael Riley, “however, we are concerned the facility is accepting and storing more [debris] than it is processing and sending off site.”

In mid-January 2017, the Ohio EPA ordered Arco to shut down. The agency said the pile of debris at the site had grown even larger since the 2016 visit, measuring 50 feet tall, 500 feet long and 600 feet wide—the equivalent of five professional football fields.

“The regulators, the EPA and the county board of health and division of air quality, they did what they could within the confines of existing laws and regulations,” Bickett said. “In some ways their hands were tied, but we think they probably could have shut them down sooner.”

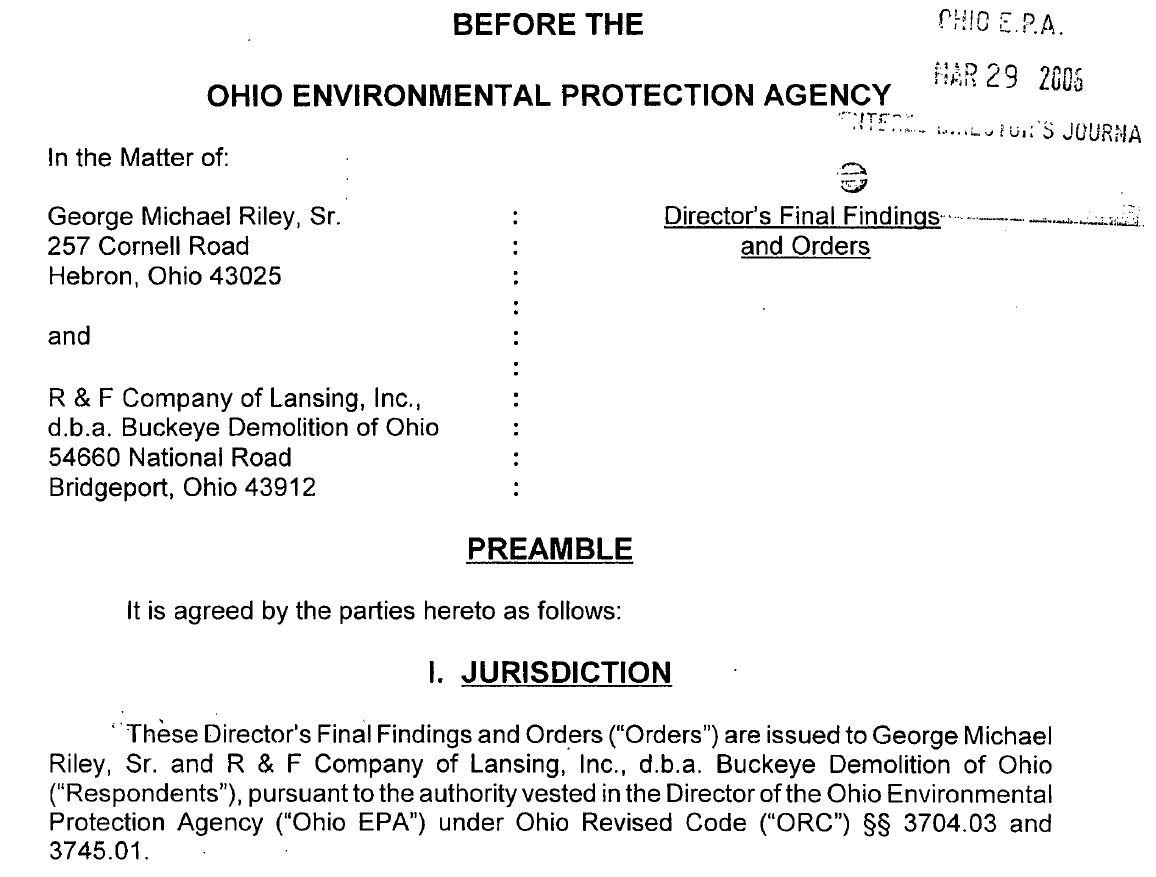

Riley had run into trouble with the Ohio EPA years earlier. In 2002, the Ohio EPA cited him for demolishing an old glass plant in St. Clairsville without notifying the agency first. Riley left the debris pile on the site for months, according to a 2006 agency order.

A 2006 order from the Ohio EPA issued to George Michael Riley Sr. [Ohio EPA]

A 2006 order from the Ohio EPA issued to George Michael Riley Sr. [Ohio EPA]

After the state attorney general threatened a lawsuit, Riley agreed to a $6,000 settlement, according to the 2006 order.

A decade later, a similar script was playing out again. As the Ohio EPA shut down Arco, the attorney general’s office prepared a lawsuit.

Riley claimed in a court filing that he had left Arco by the time of the Ohio EPA’s shutdown order. An Ohio EPA letter refers to “reorganization of management” in August 2016, and Riley’s name stopped appearing on Ohio EPA documents included with AMW Salvage land bank contracts around that time.

But Riley didn’t leave the demolition business. As Beynon and her attorney appealed the shutdown order, Riley continued to receive public contracts for demolitions, taking the refuse elsewhere.

Riley’s new company, Red Rock Services, received about $1 million in contracts from the land bank in late 2016 and 2017, according to land bank records.

Frangos told ideastream that Red Rock had been found qualified to work as a demolition contractor. He wrote that the land bank understood that Riley was no longer involved with Arco.

The last contract Riley signed with the land bank is dated May 26, 2017—months after the Arco shutdown and about a week before the state attorney general filed suit against Riley and Beynon.

“We advised Red Rock that we wanted to suspend working with the company until such time as the legal cloud over Mr. Riley’s involvement with the Arco Recycling facility was cleared,” Frangos wrote.

Cuyahoga County health officials and East Cleveland Mayor Brandon King discuss the fire at Arco Recycling in October 2017. [City of East Cleveland]

The state and Cuyahoga County set to work cleaning up the site in 2017. In October of that year, multiple emergency crews battled a fire that burned for days inside the large pile of refuse. Contractors eventually removed more than 327,000 cubic yards of debris, according to the county board of health.

Then-Gov. John Kasich signed a bill in 2017 giving the Ohio EPA more power to regulate construction and demolition debris recycling facilities.

“The situation at Arco was the impetus for us asking for this legislation,” Griesmer said.

Neighbors sued Arco, alleging that they noticed “toxic smells” and complaining of “years of vibrations from the nonstop procession of dump trucks.” In October 2018, they won by default. Judge Carolyn B. Friedland awarded more than two dozen people $75,000 each.

No one from Arco Recycling ever responded to the suit in court.

Lawsuits And A New Life In Steubenville

Noble Road neighbors aren’t the only people who say they’re owed money.

Arco Recycling, AMW Salvage and Red Rock Services face several lawsuits across multiple local courts. In total, the three companies have been accused of failing to pay more than $125,000 in bills.

The parties have settled some claims, and other lawsuits are ongoing. Christina Beynon filed for bankruptcy in 2017, placing most civil suits against her on hold.

Riley now appears to be spending time in eastern Ohio. His official address, according to court records, is in Martins Ferry, an Ohio city outside Wheeling.

Appliance Depot opened in 2017 in Steubenville. Riley is the company's registered agent. [Google Street View]

Appliance Depot opened in 2017 in Steubenville. Riley is the company's registered agent. [Google Street View]

At a Steubenville City Council committee meeting in September 2017, a councilman announced that a developer from Cleveland planned to open a new business downtown at the site of a former furniture and appliance store, according to the Herald-Star newspaper.

The following month, business records show, Riley filed papers to create a new company, Appliance Depot Inc.

In October 2017, Steubenville’s then-mayor helped cut the ribbon at Appliance Depot. A Weirton Daily Times photograph shows him sharing a pair of scissors with LaTasha Atteberry, Riley’s business associate from RCI Services.

Riley applied in February 2018 to change his name to Anthony Michael Castello, according to a filing in Jefferson County Probate Court. A judge granted the request in April.

This February, a new company formed next door to Appliance Depot, according to state business records: The Deli on 4th Street.

The company’s registered agent is Anthony Castello.

This story originally used the word "assessed" to refer to 1705 Noble Road's estimated $250,000 value. A more accurate term is estimated market value. The assessed value is the amount subject to property taxes.