A Place Of Hope

Come with us on a road trip, about an hour east of Cleveland, to a farm in the most rural section of Trumbull County. It sits amid Amish communities and land that has been tended by hand for generations.

Except these 300 acres are helping people learn how to tend to their own needs. Hopewell opened in 1996 but odds are, you’ve never heard of it. The people who run this therapeutic farm community for people with mental illnesses would like to change that.

They’d also like to change how the United States treats people with diagnoses that bring them to Hopewell.

ideastream’s in-depth local reporting is made possible by donations from supporters like you.

Join us as a Member now.

ideastream.org/donate

Creating a Sense of Community

Budding photographer Amanda Wagner has lived at Hopewell for two years.

“I was in and out of in-patient, out-patient hospitals since I was 16 because I was very depressed,” Wagner said. “I was diagnosed with schizoaffective [disorder] when I was 21 years old and my father passed away. So that really just put a downfall in my head really… took away my life, pretty much.”

A life she’s trying to rebuild at this tranquil site about a mile outside the hamlet of Mesopotamia, Ohio, where horse-drawn buggies share two-lane roads with pickup trucks and neighbors are few.

Approximately 1 in 5 adults in the United States experiences mental illness in a given year – that’s 46.6 million people. But only 41 percent of those adults with a mental health condition received mental health services in the past year, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

There is no typical story about how or why a person gets to Hopewell, which is the sole facility of its kind in Ohio and one of only five therapeutic farm communities in the United States, each with its own focus and approach. But for most of those here, Hopewell is not their first residential treatment situation.

“For many of our residents, coming into a facility like this a really just a proverbial breath of fresh air,” said Laura Scarnecchia, Hopewell’s admissions director. “They’ve been in and out of treatment facilities, they’ve been in and out of hospitals, many in restrictive or lock-down units, and a lot of people are tentative about exploring Hopewell because that is precisely the environment they don’t want to be in. They’re looking for something freeing, something where they can engage in a meaningful community.”

Creating a sense of community is key to healing at Hopewell, according to its staff. People come to the farm with a desire for treatment – a facility requirement – and an interest in learning more about their diagnosis, how to cope with it and how to live with and get along with others, explained Daniel Horne, the facility’s clinical director.

“Most folks who come to us, by the time they come to us, they’ve lost all sorts of connections to the community,” Horne said. “They’ve lost work, the ability to work. They’ve lost the ability to be in school. They’ve lost connections at church, they’ve lost connections to family – quite frankly, lots of family members start getting scared and pull away from people with mental illnesses.”

“They come in – this is going to sound so dramatic but – shattered,” he said.

Residents are at least 18 years old, usually with a primary diagnosis of a mood or thought disorder such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder or major depression. Stays typically last between five and nine months, but are tailored to individuals’ treatment plans, progress and needs.

Hopewell stresses four pillars of treatment:

- the healing power of nature;

- meaningful work;

- participation in a therapeutic community; and

- clinical engagement, including individual and group therapy and adherence to prescribed regimens of psychiatric medications.

“Medication remains critical,” Horne said. “These mental illnesses cause significant brain challenges and the medications can help. They can put them in a state of mind that allows them to take advantage of what we have to offer here at Hopewell.”

Hopewell’s approach to therapy reflects a detailed and deeply-researched, 24/7 care strategy, currently overseen by Executive Director Jim Bennett. Hopewell residents have a true sense of well-being about what this place does, Bennett believes, “because of the supportive environment that we’re absolutely committed to, each and every one of us who are here.”

“Another way to describe it is a total change of environment from where they were before: isolated, by themselves psychologically and often feeling alone and not connected with people. And here they are connected to people all the time. They sleep in the cottages, they dine together. They do work groups together. And so the human fabric is stitched together here to make that healing environment.”

Hopewell’s 60 full-time, part-time and associated clinical staff outnumber the residents, about 30 or so during our visit in the summer of 2019. Every one of those employees has a special skill set.

Amanda Wagner, Hopewell resident. "Hopewell gives you a sense of independence. You can go anywhere you want, just get out and walk to the Commons or the Dollar Store by yourself… you have a sense of freedom."

Amanda Wagner, Hopewell resident. "Hopewell gives you a sense of independence. You can go anywhere you want, just get out and walk to the Commons or the Dollar Store by yourself… you have a sense of freedom."

Laura Scarnecchia, Hopewell’s admissions director. “Many families find us when they're looking for treatment online. There aren't a lot of residential mental health facilities around, so they have done some Googling. They've talked to friends, they've talked to providers…. people come from all sorts of places and have been referred by all sorts of people.”

Laura Scarnecchia, Hopewell’s admissions director. “Many families find us when they're looking for treatment online. There aren't a lot of residential mental health facilities around, so they have done some Googling. They've talked to friends, they've talked to providers…. people come from all sorts of places and have been referred by all sorts of people.”

Daniel Horne, Hopewell’s clinical director. “They come in having spent the last year and a half of their life essentially either… everybody’s different but, holed up in the room, playing video games all day and just not living any kid of life. And for the most successful and most people that come here get to some degree of feeling confident that they can go out and live a more independent, rich, full life."

Daniel Horne, Hopewell’s clinical director. “They come in having spent the last year and a half of their life essentially either… everybody’s different but, holed up in the room, playing video games all day and just not living any kid of life. And for the most successful and most people that come here get to some degree of feeling confident that they can go out and live a more independent, rich, full life."

Jim Bennett, Hopewell’s executive director. “I feel that I'm making a contribution that I'm able to be part of the community and help it be a better one and that our residents are truly remarkable people on the journeys they're on… The pay is not what brings people here, it's the community, the compassion, the commitment to helping the mentally ill make that journey.”

Jim Bennett, Hopewell’s executive director. “I feel that I'm making a contribution that I'm able to be part of the community and help it be a better one and that our residents are truly remarkable people on the journeys they're on… The pay is not what brings people here, it's the community, the compassion, the commitment to helping the mentally ill make that journey.”

More Than Medication And Meditation

Hopewell is a working farm, with chickens, cows, pigs and goats. Residents and staff together grow most of the vegetables they eat and even produce maple syrup on site.

Hopewell is a working farm, with chickens, cows, pigs and goats. Residents and staff together grow most of the vegetables they eat and even produce maple syrup on site.

Abbey Taylor, Hopewell resident. “Obviously mental health is a journey that involves a lot of people, but at the end of the day, it’s work that I have to do myself and that I have to hold myself accountable for. But to have this community of people around me cheering me on and who are there if I want to ask questions or I’m having a bad day, there is a lot to be said for that support... this is, in a lot of ways, a journey that I have to take myself but I’m never truly alone."

Abbey Taylor, Hopewell resident. “Obviously mental health is a journey that involves a lot of people, but at the end of the day, it’s work that I have to do myself and that I have to hold myself accountable for. But to have this community of people around me cheering me on and who are there if I want to ask questions or I’m having a bad day, there is a lot to be said for that support... this is, in a lot of ways, a journey that I have to take myself but I’m never truly alone."

The farm's herd of Belted Galloway cows came to Hopewell as a donation from a retiring cattle rancher and provide a work opportunity as well as food for residents. The Scottish breed's long, thick hair makes them well-suited for enduring Northeast Ohio winters.

The farm's herd of Belted Galloway cows came to Hopewell as a donation from a retiring cattle rancher and provide a work opportunity as well as food for residents. The Scottish breed's long, thick hair makes them well-suited for enduring Northeast Ohio winters.

About 90 percent of the produce consumed at Hopewell is grown here by residents and staff.

About 90 percent of the produce consumed at Hopewell is grown here by residents and staff.

Program Services Supervisor Jack Childers lives on the farm. He oversees the residents who do much of the daily work here.

“It’s vital to our mission at Hopewell. Without the work crews, we’d be like so many other places,” Childers said. “With the work crews, it allows them to take part in meaningful work, not just busywork. They’re actually helping the running of the farm here at the same time they get to see the results of their work, which I think is very rewarding.”

Residents get traditional clinical treatment like cognitive behavioral therapy and individual and group counseling, as well as learn practical skills like money management, meal planning and how to interview for a job. But at Hopewell, residents go beyond the traditional. They have access to meditation, nature-focused eco-therapy, art therapy and other forms of creative expression. And everyone is assigned to some form of “therapeutic work activity,” from collecting eggs to helping with maple syrup production.

“A lot of people here, myself included, have been institutionalized prior to being here. And just the whole approach is completely different here,” said Abbey Taylor, 21, a Hopewell resident 13 weeks into her stay. “More focused on the value of the person. Even just expecting us to go to work crews, that means A, we value the work you put in and B, we believe you could do it.”

Before Hopewell, Taylor was familiar with residential treatment, she said, but not with farming. Being among so many animals makes working through her treatment for depression, anxiety and PTSD at Hopewell feel more like a home, she said.

“Even if you don’t love animals, you know, there’s 200 acres of woods out there,” Taylor said. “I know there is a big emphasis on being out in nature here. And I think that’s definitely really important. We have nature walks and we have an eco-therapy group. We have a conservatory and a greenhouse so we grow all kinds of plants. I think it’s very therapeutic just to be trying to look for the little things and there are so many little things to appreciate in nature, even just the little chicks we have over here, they’re so cute.”

Caring for cute chicks, 300-pound pigs, cows and horses isn’t the only non-standard therapy here.

Hopewell is very much a working farm. Residents tend large gardens under Cindy Wagner’s supervision, growing about 90 percent of the vegetables eaten here and seeing firsthand their contributions matter.

“When we plant seeds in the garden, we watch them grow, just like all of us, we grow,” Wagner said. “That’s the best part about Hopewell, is to see residents come in and then we can just watch them grow and be empowered to find meaningful work here at Hopewell.”

Wellness Educator Jennifer Miller has turned the crops and animals raised here into meals for eight years now. She says good nutrition directly impacts mental and physical health. Eating well is part of the treatment.

“We want to give the residents the best nutrition that they can possibly get. We try to fit in as many vegetables and whole foods as we can,” Miller said. “We try to stay away from processed foods. Nutrition is vital to the mind, in the development of the mind as far as mood, memory.

“So the more whole foods, the more healthy foods that we can give them, the better off they’re going to be mentally,” she said.

Some prefer to use their hands in other, still therapeutic, ways.

Like joining Hopewell’s house band.

Called “Musical Journey,” its rotating cast of musicians mostly includes residents, but on guitar is Jim Miller, band leader and Hopewell therapist.

Miller says his players bond and learn responsibility from behind their drums, keyboards and other instruments. The group chooses three or four songs, rehearses for about an hour a week and does shows for the rest of the farm.

“Music, I think, is the greatest therapy,” Miller said. “Number one, you forget all your troubles when you’re working on it. You have to concentrate and work on you and the music.”

Music helps heal more than just the residents, Miller said.

“There's a lot of group therapy and a lot of individual therapy here and a lot of recovery. So anything to do with that is also incorporated in the Musical Journey group. And the name says it all,” he said. “And I've shared some things about myself with my partners here and so and I've done some recovery myself. And that's sort of also what music is about and music therapy.”

“And then there’s this sense of accomplishment. So not only is the time spent, maybe the three months we spend working a process that is in many ways spiritual and in many ways healing, but it’s a great sense of accomplishment for everybody. ”

The visual arts are also a therapy option.

Mary Cassidy runs Hopewell’s art therapy program. She loves having the artists create while outdoors, which Cassidy says helps residents express themselves.

“I explain it to folks as sort of having a conversation with your subconsciousness or your unconsciousness,” Cassidy said. “So it gives you an ability to maybe learn a little bit more about yourself, maybe build some insight or awareness into some things that are happening in the moment while you’re in recovery and while you’re going through this oftentimes challenging and difficult healing journey to have it have a way to just kind of get out.”

Jim Miller, band leader and Hopewell therapist. “There's a spirit here and I believe the staff carries that spirit, and the people that come through catch the spirit that's here at at this beautiful place."

Jim Miller, band leader and Hopewell therapist. “There's a spirit here and I believe the staff carries that spirit, and the people that come through catch the spirit that's here at at this beautiful place."

Hopewell resident Jared, who prefers to be identified only by his first name, rocks a Tom Petty cover with the house band.

Hopewell resident Jared, who prefers to be identified only by his first name, rocks a Tom Petty cover with the house band.

Mary Cassidy, Hopewell's art therapist. “More and more, we're finding that reconnecting with our senses or through sensory experiences are really, really powerful ways to help people heal and work through their challenges and issues.”

Mary Cassidy, Hopewell's art therapist. “More and more, we're finding that reconnecting with our senses or through sensory experiences are really, really powerful ways to help people heal and work through their challenges and issues.”

Hopewell resident Cameron, who prefers to be identified only by his first name, paints in an art therapy session.

Hopewell resident Cameron, who prefers to be identified only by his first name, paints in an art therapy session.

Does It Work?

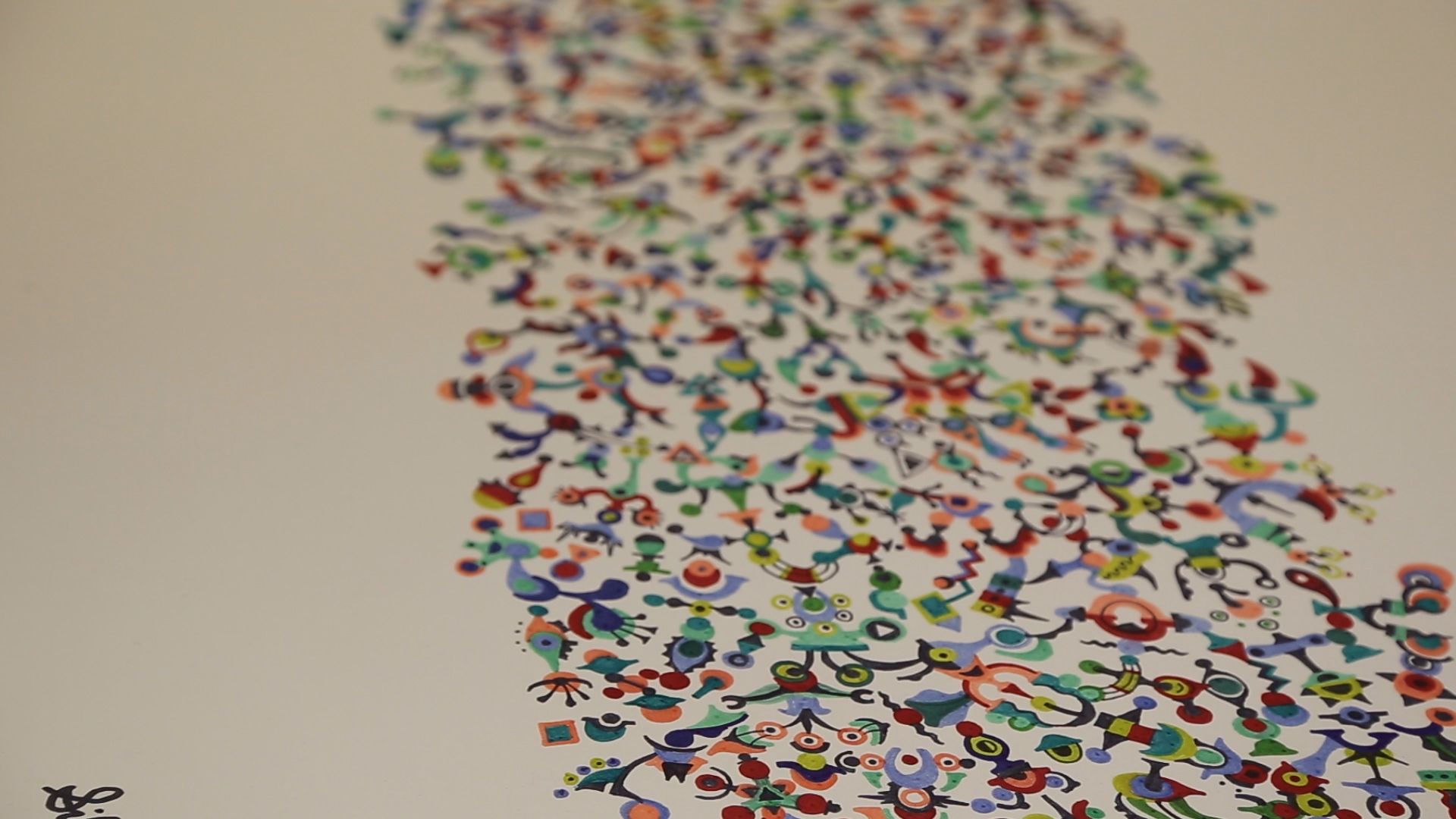

Sam Silverman is one of the artists who made it through that “challenging and difficult healing journey.” He left Hopewell five years ago and says the months he spent there made a huge difference in his artwork and in his life.“I was struggling with mental illness,” he said. “I was wandering a lot. I wandered around the West Coast, which is actually what gave me a lot of the inspiration for my artwork and the style that I create with my visual art, so it wasn’t all bad. But I think I was pretty lost and Hopewell helped me to find my place.”

At the peak of his mental illness, before Hopewell, Silverman said he had lost his drive and motivation for creating art – a dark place to be for someone who had been playing piano since around age 5, composing music at 13 and making visual art all his life.

The coping techniques, contact with nature and sense of community at Hopewell rekindled his creative spark, Silverman said, and at the same time, he learned to do more than accept his diagnosis and learn to deal with his mental illness: “I came to kind of embrace it.”

He carries on that sense of community from Hopewell in NAMI programs and with the group of artists he is now part of in Cleveland. He makes art that brings together his music composition and visual art skills.

“My artwork is most music-based because I have something called synesthesia, which means that I see sounds and I hear shapes and colors,” Silverman said. “My number one goal is to be interesting. I want my art to be something interesting to look at. I call them sound worlds, the term that they came up with to describe these visual maps of sound that I create.”

And spreading the hope he found at Hopewell to anyone who needs it.

“Hopewell was really just an amazing thing for me,” he said. “That's the best way that I can say it, because things really just turned around for me in general from being at Hopewell and I think they can for other people, too. So yeah, I want to say that if you're struggling with mental illness that there is a place that you can go out in nature where you can recover and be among other people who are struggling with the same things that you are.”

But is there more than anecdotal evidence that this emotional healing, manifested through hard work and service, actually helps?

Dr. Martha Schinagle of University Hospitals crunches the numbers from Hopewell and tracks its alumni.

“Some people I’ve continued to follow and work with a handful of people after they’ve left Hopewell. And I can tell you that, I mean they do great. The people that I’ve seen do great,” Schinagle said. “It’s not like instantly they come out and everything’s good. The first year is a big adjustment and hard work to get sort of settled into life outside of Hopewell. And to find their way. But they learned the tools and the skills while they’re at Hopewell.”

About 50 percent of Hopewell’s alums go back to live with their families, she says. Between 20 and 30 percent end up in group homes and the rest often live independently, which can be seen as a pretty big accomplishment for some, depending on their diagnosis.

That sense of accomplishment is not always shared by insurance companies. Months of intensive residential care that can carry a price tag of hundreds of thousands of dollars is not cost effective in their eyes.

Limited or even non-existent reimbursements have kept the number of people who can benefit from Hopewell’s program well below its capacity.

Residential treatment in general costs between $10,000 and $60,000 per month. Hopewell officials say costs there are on the lower end of that scale and most residents rely on their own resources along with limited insurance benefits. And the farm does work with some families to help subsidize some costs.

“The impact that places like ours are going to be able to make is going to be constrained unless and until insurers and government funding start to realize that if you want to help people be independent and recover from mental illness, you cannot do it through short stays in institutions,” said Bennett.

Sam Silverman, artist, musician and former Hopewell resident. “Just doing the chores on the farm – feeding the animals, collecting the maple syrup, waking in the woods in nature. I mean, these are things that really heal a person and I think other facilities may not be like that. A hospital wouldn’t enable you to be out in nature and to feel so free and so good.”

Sam Silverman, artist, musician and former Hopewell resident. “Just doing the chores on the farm – feeding the animals, collecting the maple syrup, waking in the woods in nature. I mean, these are things that really heal a person and I think other facilities may not be like that. A hospital wouldn’t enable you to be out in nature and to feel so free and so good.”

A Healing Community, One Person at a Time

Short stays are ever more the norm, said Hopewell’s founder and driving force, Clara T. Rankin.

At 102 years old, she’s still strolling the gardens in her signature wide-brimmed blue hat, hugging residents when she gets the chance. But rising costs and insurance coverage that isn’t as good as it could be seem to be contributing to shorter stays than when the farm opened in 1996, she said.

”They do leave sooner than in the old days,” Rankin said. “And that may be because the treatment is better. Or that they can't pay any longer. So, that's not fair.”

When she had the initial vision for Hopewell, there wasn’t much residential treatment for mental illness close to Cleveland, she said, so she saw a clear need.

“I wanted a peaceful place. Where people could go without feeling stress,” Rankin said. “And where they could work with the earth, because I feel that’s very important, to be able to put your hands in the soil.”

When she bought the property, more than one member of the local Amish community came to tell her that this is a healing place. If she believes that healing power is in the actual ground under her feet, Rankin isn’t telling. But the land and the community she has built on it continues to mend minds and lives, one day – and one individual – at a time.

“The thing I like about it is that they treat each person as an individual. In the sense that it's not a whole pattern for everybody,” she said. “Each, as an individual, has to have his own or her own way of going. But while they're doing that, they are a community.”