Making Art Work

Meet Michelangelo Lovelace

Editor's note: There has been ongoing conversation in Northeast Ohio about artist support in recent years, but little examination of how artists support themselves on a day-to-day basis. Through this series, ideastream highlights a sampling of area artists and the various ways they make their finances work.

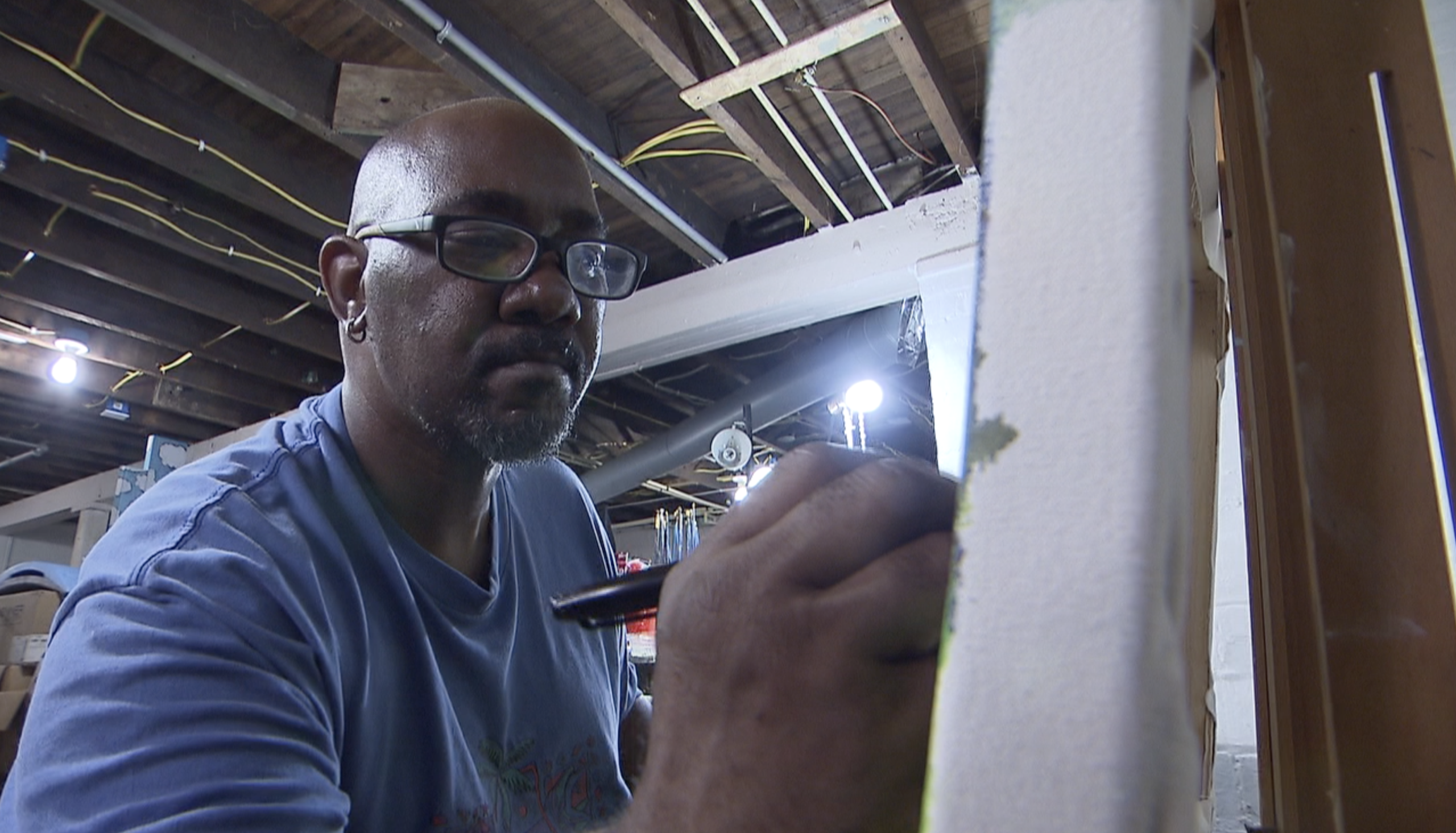

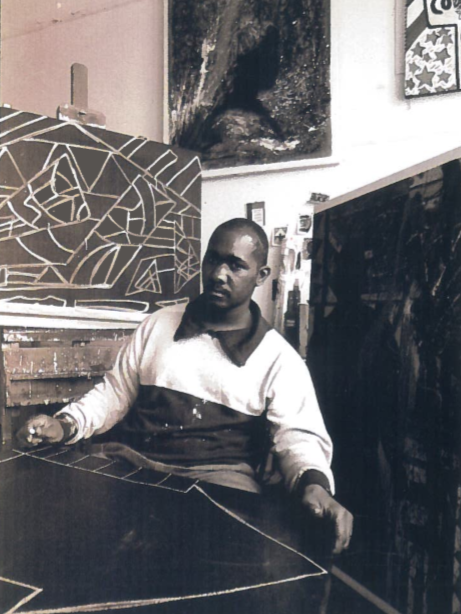

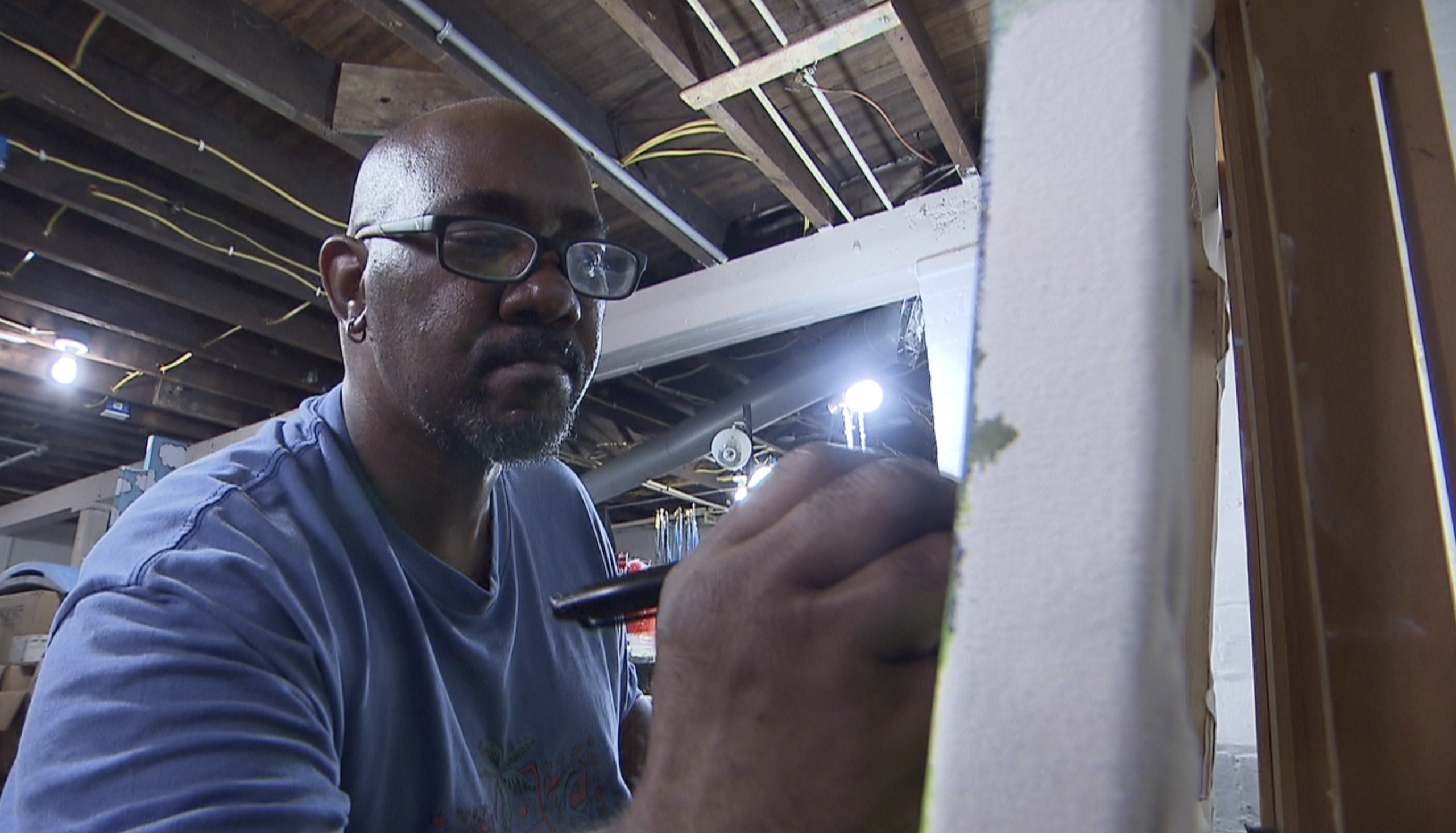

Michelangelo at work in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo at work in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

By day, artist Michelangelo Lovelace heals others as a health care worker. At night, he nurtures his art. Painting for three or four hours a night, he pursues his lifelong passion and over the years developed a recognizable urban-folk art style reminiscent of “outsider” artists. While he doesn’t rely on his art to pay his bills, he recently sold out a gallery exhibition in New York.

ideastream’s in-depth local reporting is made possible by donations from supporters like you.

Join us as a Member now.

ideastream.org/donate

GROWING

UP IN

CLEVELAND

Born Michael Anthony, Lovelace goes by Michelangelo, a childhood nickname from his friends. He describes his paintings as a “documentation of urban life,” a snapshot of his experiences growing up in King Kennedy Estates, a subsidized housing complex in Cleveland’s Central neighborhood.

King Kennedy Estates, Cleveland, Ohio. [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

King Kennedy Estates, Cleveland, Ohio. [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

The area has struggled with high unemployment, low income, crime and drugs. As a child, Lovelace began to draw as a way to cope with his surroundings.

“I can remember as a young kid going to Head Start. Them giving me crayons and drawing pictures,” he said.

As a teen, Lovelace’s interest in art gave way to time on the streets and a brush with the law. At a court appearance on a drug charge, the judge asked if he had any skills. He replied that he could draw. The judge then offered him some advice. “’Get to drawing because if you show up in my courtroom again, you’re going to jail,’” Lovelace recalled.

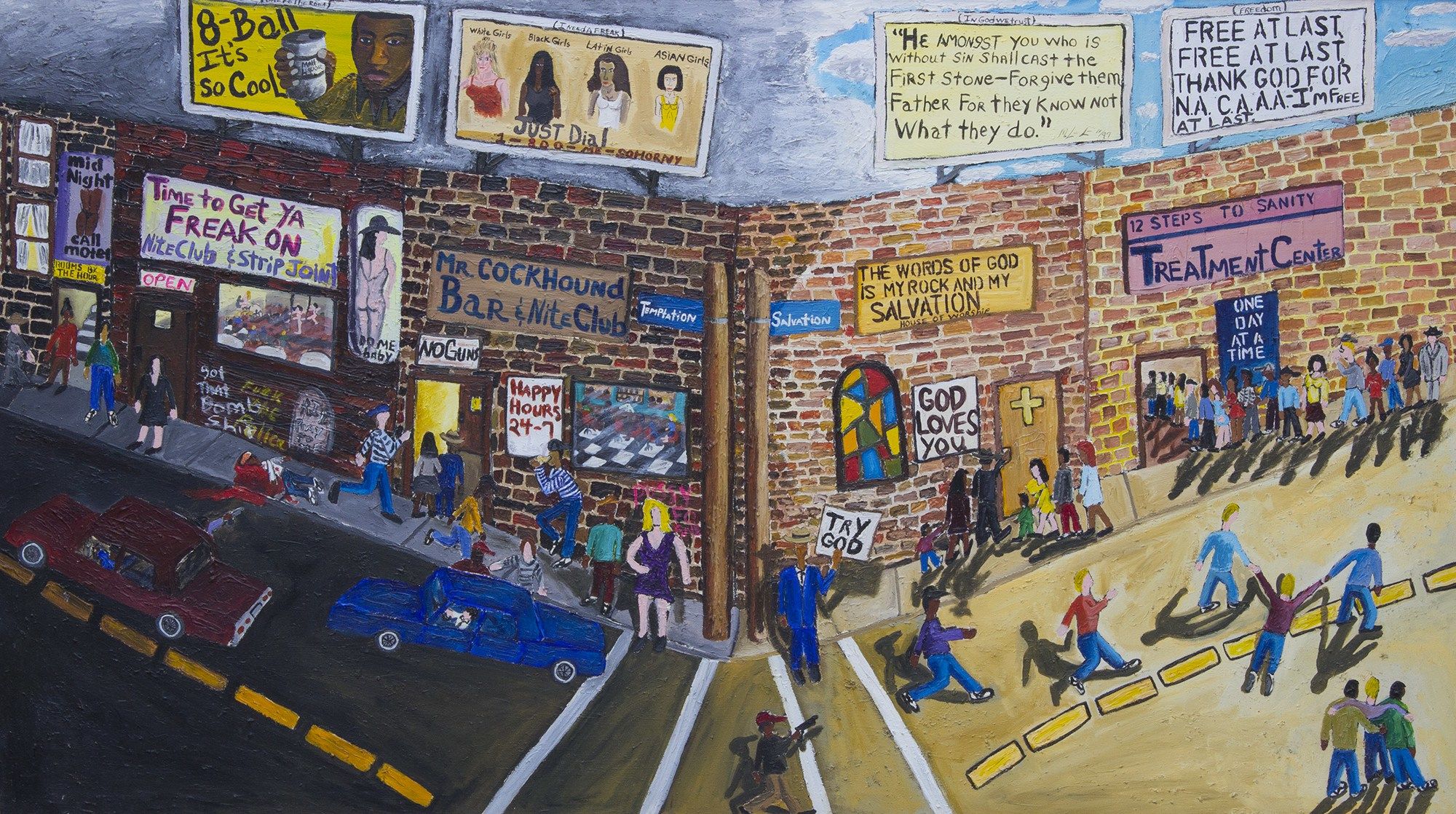

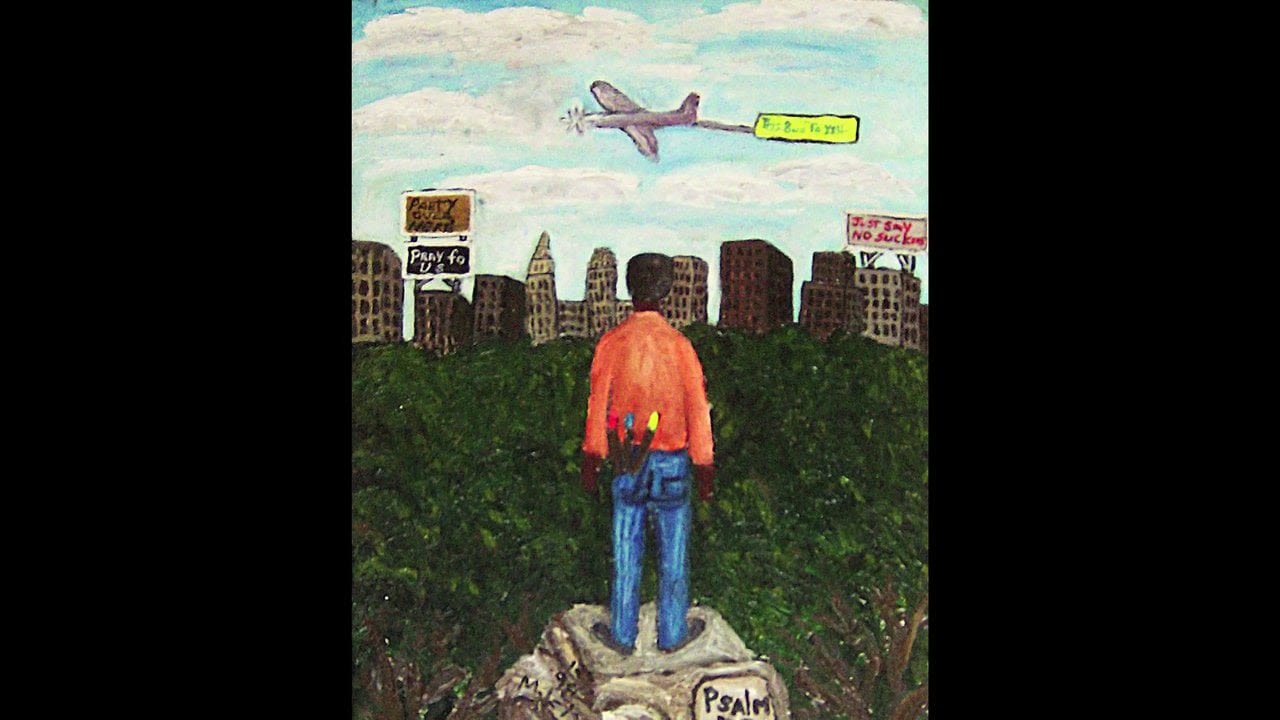

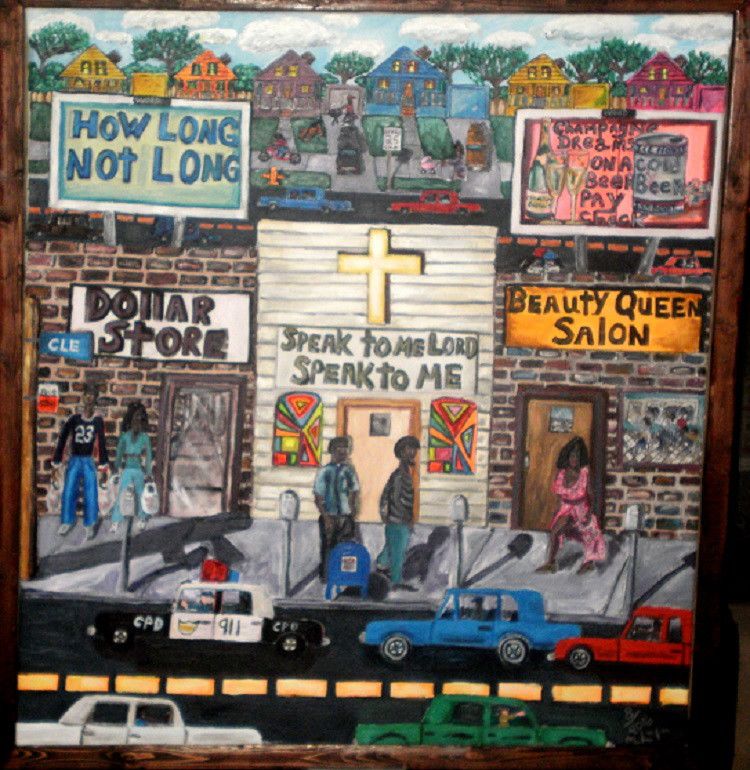

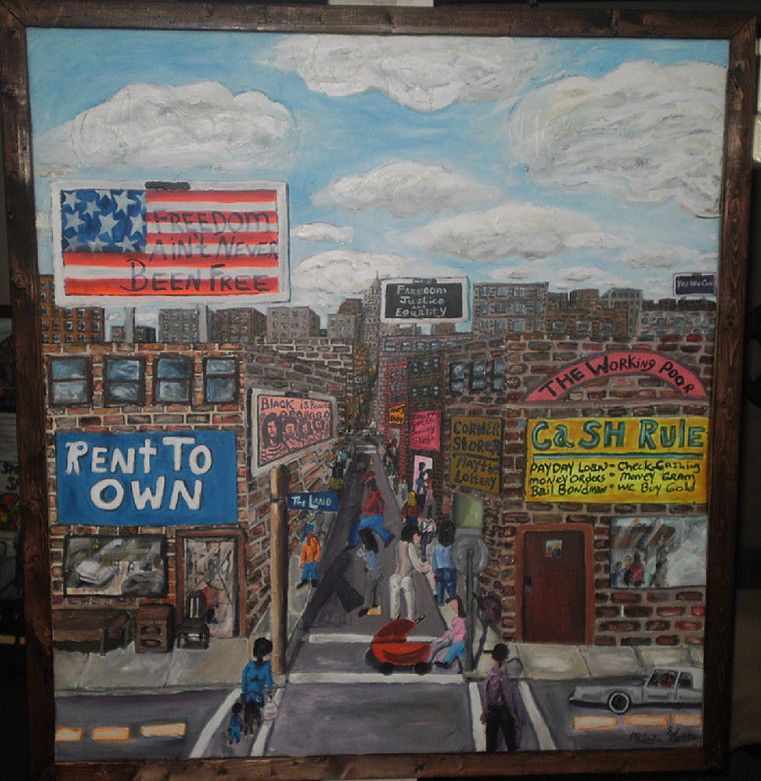

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

With that, he committed himself to art.

“I needed a way to express myself. Growing up in the inner city living in housing projects I found that art gave me an escape. It gave me a way to express myself in a way to escape from the realities of being poor,” he said.

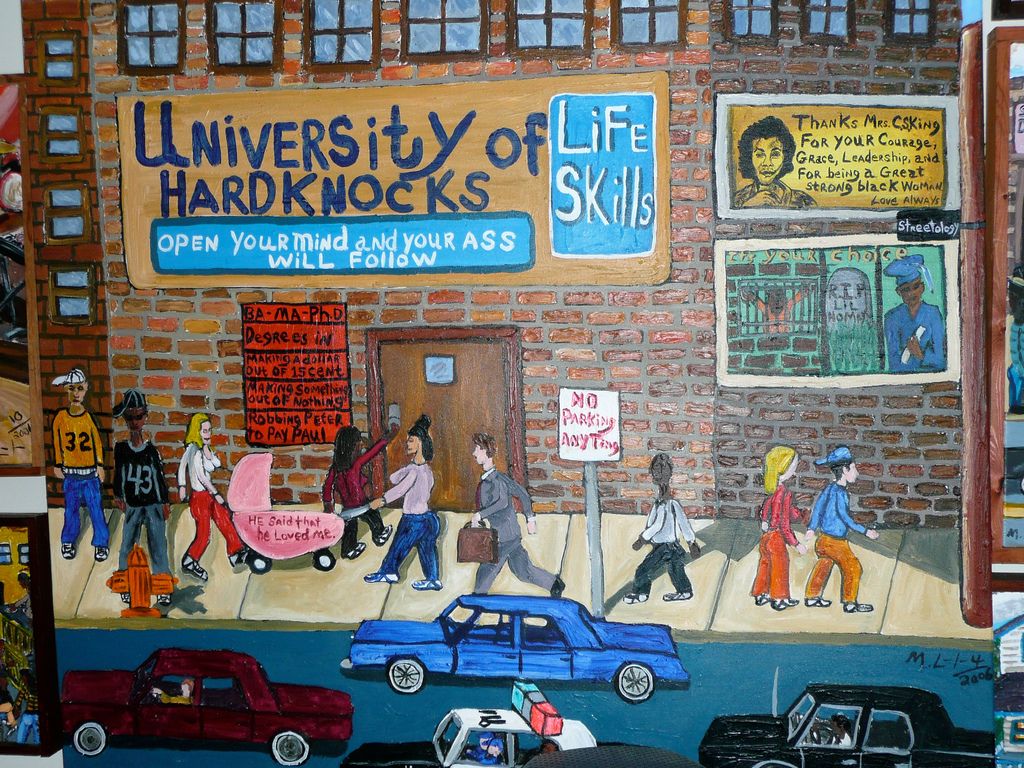

At 16, Lovelace dropped out of school to go to work to help support his family. He continued to paint, self-taught, and he developed a style similar to “outsider” and folk artists. He prefers to paint free-hand, using bold colors, simple designs, two-dimensional plans and flat surfaces to tell the story of racial injustice, police violence, poverty, racism and other social issues.

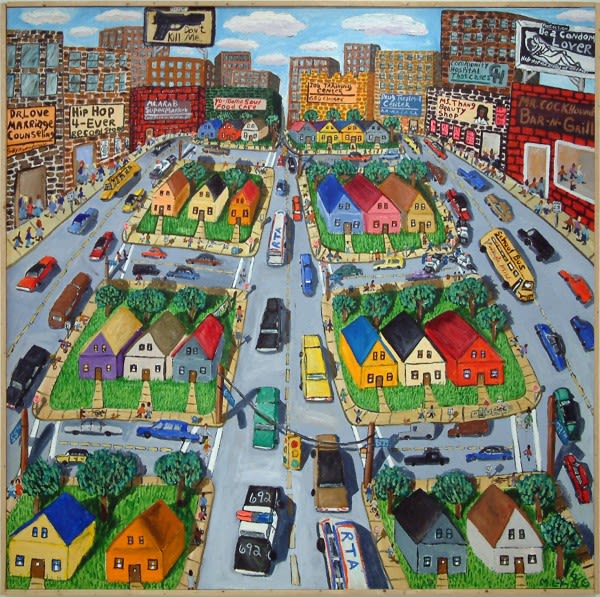

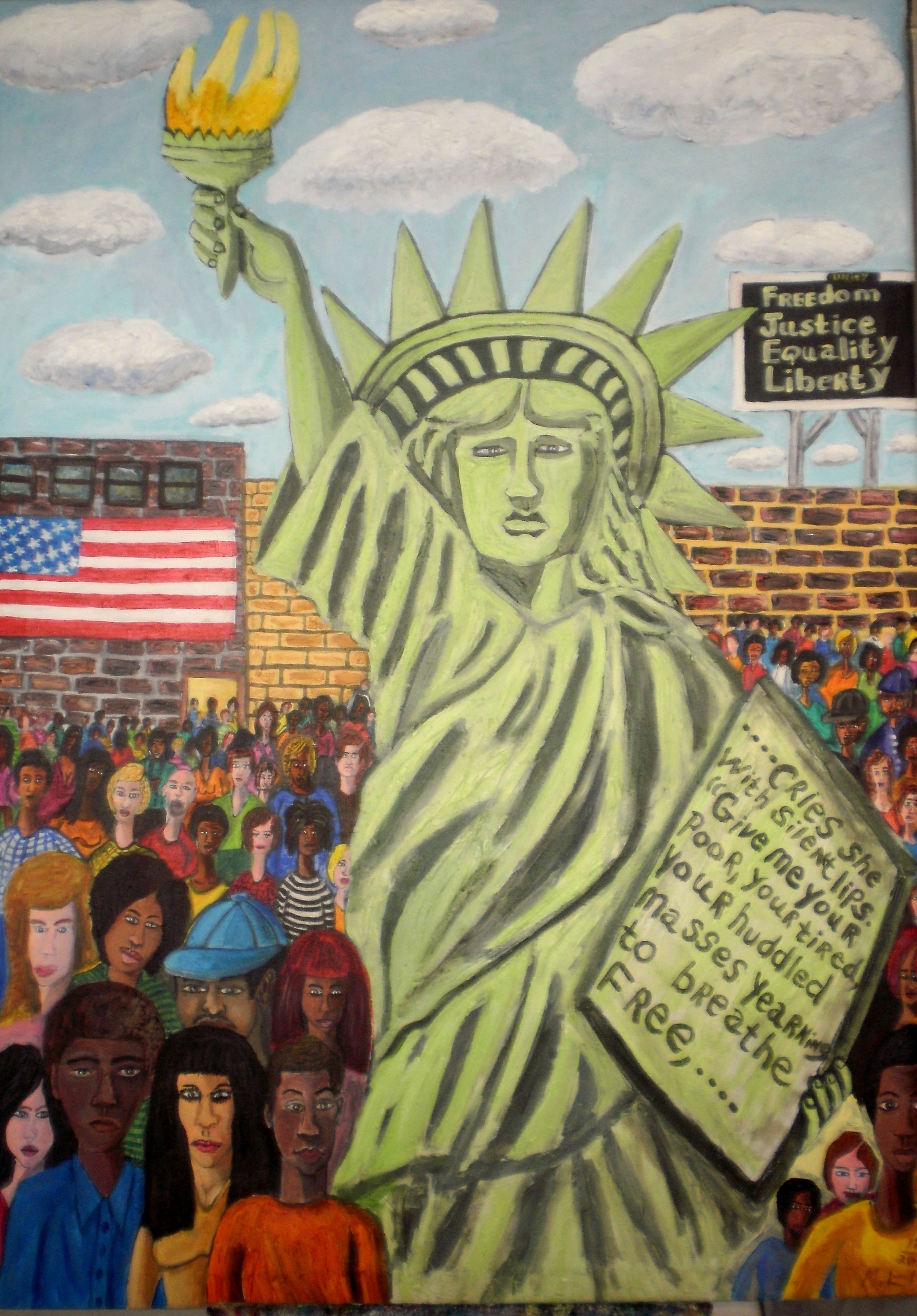

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

“There are things that happen in the inner city that can be traumatic, in a lot of ways, so I try to capture the moment,” he said. “And bring to attention the different things that happen in the city whether good or bad. "

A painting about gun violence by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

A painting about gun violence by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

[Michelangelo Lovelace]

[Michelangelo Lovelace]

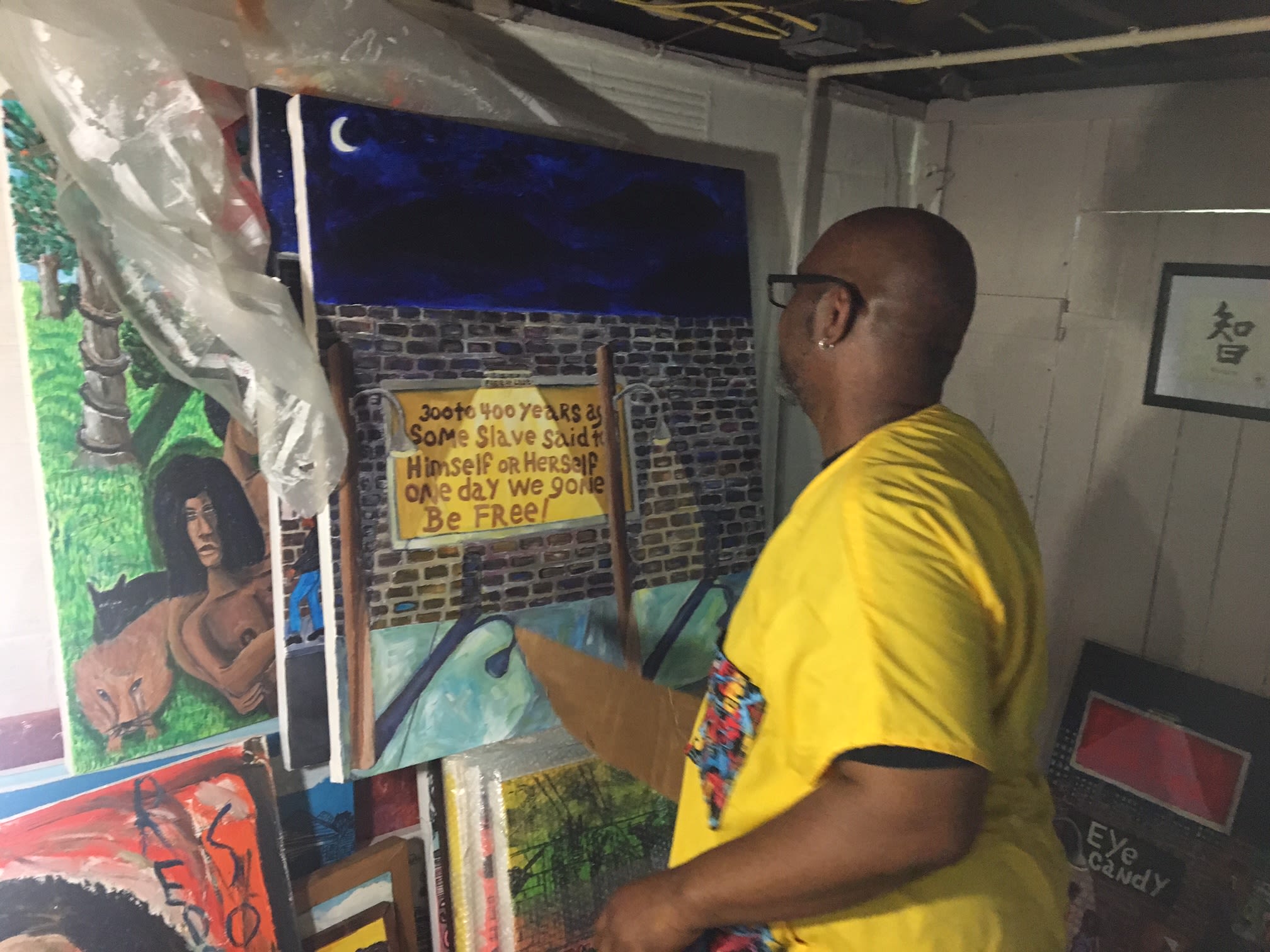

Michelangelo Lovelace stands in front of one of his pieces. [Michelangelo Lovelace]

Michelangelo Lovelace stands in front of one of his pieces. [Michelangelo Lovelace]

Michelangelo Lovelace in his studio. [Michelangelo Lovelace]

Michelangelo Lovelace in his studio. [Michelangelo Lovelace]

A

Full-Time

Job

"My job allows

me to survive."

Michelangelo in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo returned to school and completed his GED at Cuyahoga Community College. In 1985, he enrolled in the Cleveland Institute of Art, but the demands of caring for his family caused him to drop out. With help from a local non-profit, Cleveland Works, Michelangelo received training and landed a full-time job.

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

“I've been a nursing assistant since 1989. I was hired by Metro Hospital. I work for a nursing home that they own,” he said. “I've been employed there for 18 years now. My job allows me to survive. It allows me to paint whatever I want to paint, not just have to paint things to sell and be a commercial artist.”

Lovelace has a routine that ensures he puts in regular hours in his studio.

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

“Get to work at 7 o'clock, punch in, work 8 hours,” he said. “Three-thirty leave work, come home, relax for about an hour and then go into the studio for three to four hours every day.”

Steady work lightened some of the load, but it didn’t shield Lovelace from struggles as an adult.

“I've been painting since I was 19. I've been painting with my family since I was 25. And for the first 20 years, there was a lot of sacrifice,” he said. “I filed bankruptcy twice. Me and my wife were married for seven years, and then we got divorced. But we stayed friends and we raised our kids together. Then we got back together.

The two have been back together for 12 years.

A Little Help From My Friends

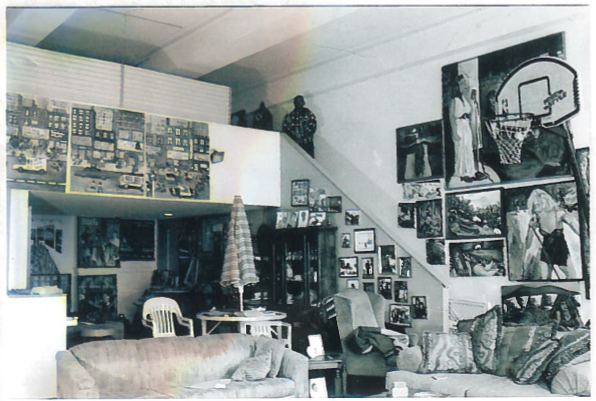

In 1992, Michelangelo moved into a bustling art complex called the Hodge at East 74th Street in Cleveland’s St. Clair-Superior neighborhood.

Michelangelo's Hodge studio apartment [Michelangelo Lovelace]

Michelangelo's Hodge studio apartment [Michelangelo Lovelace]

He found support there from his neighbor and fellow artist Omar Shaheed. “He was a sculptor and was a little bit older than me, maybe five to 10 years older… taught me how to market myself and how to put together a portfolio,” Lovelace said.

Michelangelo's Hodge studio apartment [Michelangelo Lovelace]

Michelangelo's Hodge studio apartment [Michelangelo Lovelace]

At the same time he began a friendship with famed Cleveland “outsider” artist Rev. Albert Wagner, who took him under his wing and changed his life.

The late Rev. Albert Wagner, Michelangelo's mentor, dressed in black.

“Once I met him it just opened my eyes to what being a professional artist was all about and how to be prepared and how to prepare your work so that it's always ready. And he would always say to me that ‘your time will come. Come on over and hang out and see what's going on, but your time will come. You're a great artist.’ That was the first time anybody kept saying that to me, that ‘you are a great artist. Do your work. Don't worry about it. Don't second guess yourself.’ He made the biggest difference in my life as an artist.”

Michelangelo at work in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo at work in his studio [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

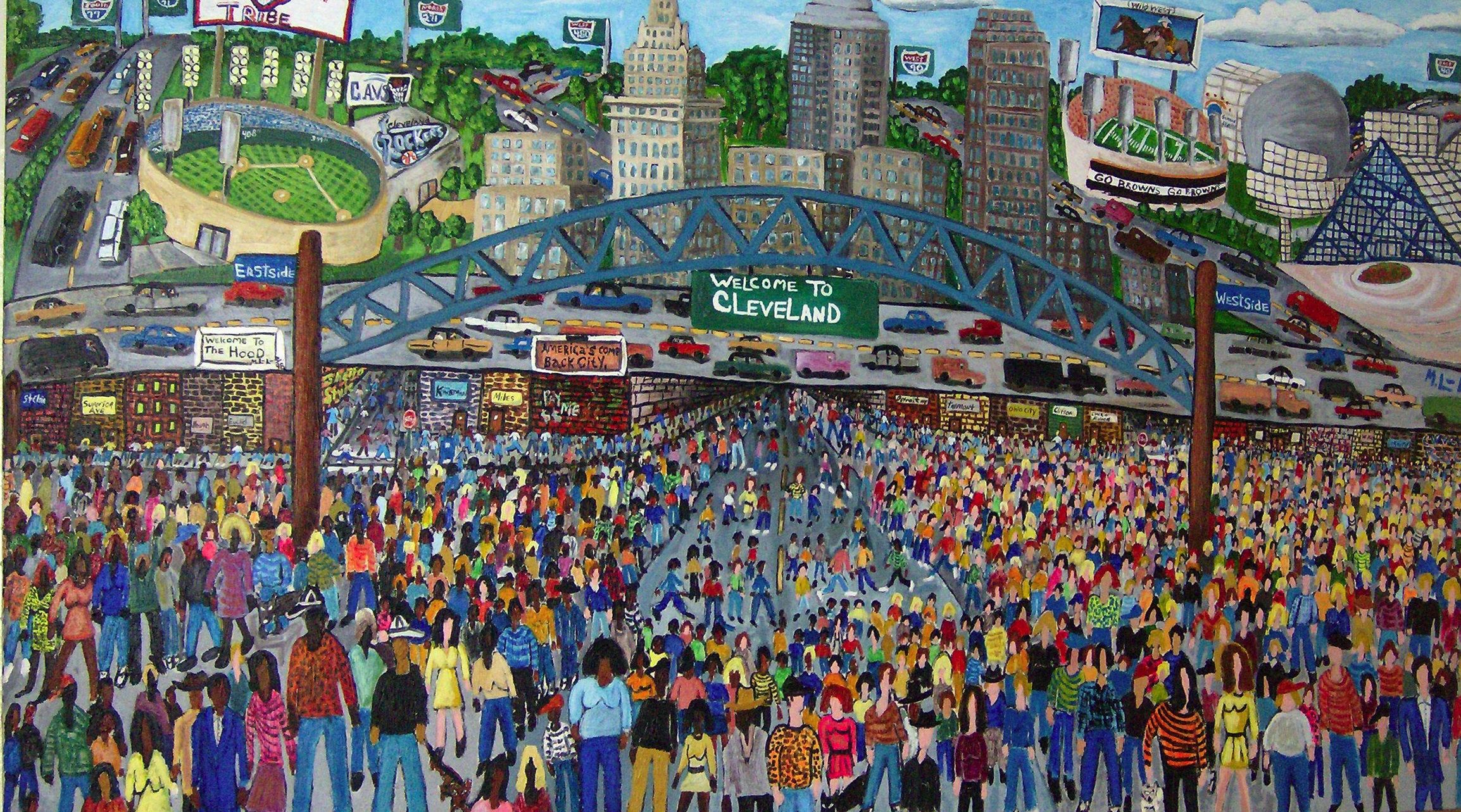

With a full-time job and support from fellow artists, Lovelace honed his skills. In time, his paintings depicting social, cultural and economic divisions between the haves and have-nots began to get noticed.

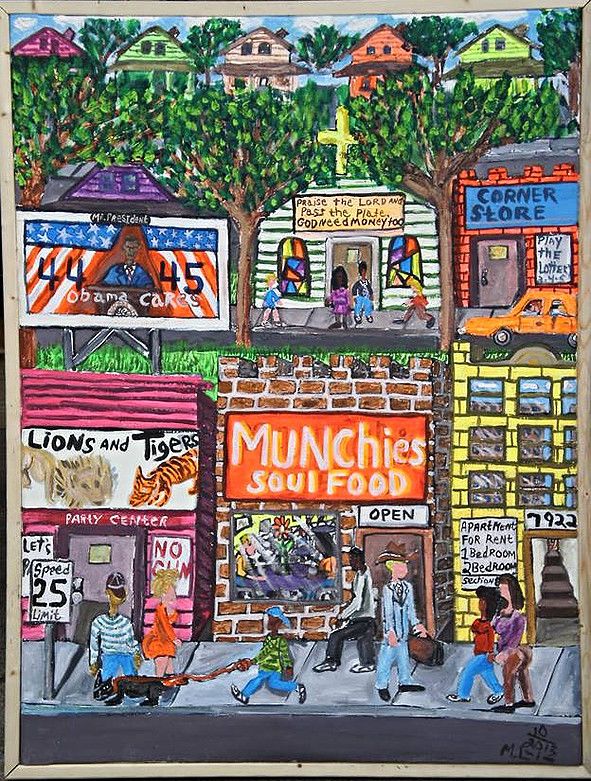

City scene by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

City scene by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

“You want to express yourself and be appreciated. I think that's one of the blessings we have in our community here in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio, is that we have a strong support system. And that support system allows you to have confidence that what you're doing is appreciated. And you can continue to do it,” he said.

Lovelace developed a following over time and people began collecting his work.

Hard Work Pays Off

In 2013, Michelangelo received a Creative Workforce Fellowship of $20,000 from the Community Partnership for Arts and Culture with support from Cuyahoga Arts and Culture.

Michelangelo at home [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo at home [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

“I really got most of my income from art from grants and fellowships,” he said. “I won the Cleveland Art Prize $10,000 fellowship. And I got a couple of jobs from the committee for public art over the years that gave me a good pay. So that was the bulk of my money that I made from art.”

Michelangelo working on one of his signature paintings [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Michelangelo working on one of his signature paintings [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

With the money from his 2015 Cleveland Arts Prize, Michelangelo went shopping for a new place to live and a better life. He wound up buying a home in the Cudell neighborhood on the West Side of Cleveland, where he converted the basement into a studio.

Michelangelo's studio (Dennis Knowles/ideastream)

Michelangelo's studio (Dennis Knowles/ideastream)

A Bite Out Of The

Big Apple

Last year, Lovelace mounted a solo exhibition in New York where he received positive reviews and sold out the exhibit.

Jillian Steinhauer of The New York Times wrote about Lovelace’s exhibit at New York’s Fort Gansevoort gallery, noting “he has a distinctive ability to dramatize the intractable social forces that threaten to drown us.”

Lovelace has found a number of ways to support his art throughout the years, but for him, art is more than making a living.

“You can't do it just for the money. When there's no money coming in, you quit doing it and you find something else to do. There's many days over the years of my 40 years that I wanted to quit because I was broke. Once I took the stigma and worry about how much money I was making, and I just went to work, when I didn't have the pressure to sell art to support myself, things got easier,” he said. “I got more confident in what I was doing. I wasn't trying to make my art pay the rent, to pay my light bill and gas bill. You know I was just doing art because I love doing art.”

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]

Painting by Michelangelo Lovelace [Dennis Knowles / ideastream]