Ohio After Roe

Chapter 2: The Pregnancy Center

By Amy Eddings & Stephanie Czekalinski

Three days before the U.S. Supreme Court decision that ended a federal constitutional right to abortion, protesters outside the Northeast Ohio Women’s Center called out to arriving patients, hoping to dissuade them from getting an abortion.

“It’s God’s baby, not yours!” called out Darlene Moss. She held a sign that read “Pro-Life is Pro-Black.”

“You might’ve been a part of it, but God gives babies! God gives life,” she added.

Moss said she planned to continue her campaign against abortion, even if Roe was overturned, as many expected would happen, and conservative Ohio lawmakers made good on their vow to ban abortion entirely.

Moss said she’d bring a different sign if that happened.

“It's going to say, ‘God will provide.’ And he will,” she said.

Another protester, Rita Vitale, said there are organizations that can provide material, emotional and spiritual support for women facing unplanned pregnancies.

“Offer them some free help – options. Let them know how valuable they are, being a life on this earth and how valuable their children are, even if it's going to be hard,” said Vitale, who says she has stood outside the clinic about once a week for the last seven years offering what she calls "sidewalk counseling."

Darlene Moss demonstrates outside the Northeast Ohio Women’s Center in Cuyahoga Falls on June 21, 2022, three days before the U.S. Supreme Court released its opinion overturning Roe v. Wade. [Amy Eddings / Ideastream Public Media]

Darlene Moss demonstrates outside the Northeast Ohio Women’s Center in Cuyahoga Falls on June 21, 2022, three days before the U.S. Supreme Court released its opinion overturning Roe v. Wade. [Amy Eddings / Ideastream Public Media]

Rita Vitale protests outside the Northeast Ohio Women's Center in Cuyahoga Falls on Thursday, June 9, 2022.

Rita Vitale protests outside the Northeast Ohio Women's Center in Cuyahoga Falls on Thursday, June 9, 2022.

Ohio Right to Life’s Mike Gonidakis said that when he learned Roe was finished, he felt both relieved and concerned.

“To be very frank, I was fearful – worried,” he said. “Because you're hoping for a day to come, and it's here … it's really here. And then the first thing I said to myself is, ‘Are we ready? Are we prepared?’”

Gonidakis said the state has entered uncharted territory, where agencies may need to help even more pregnant women and their families. Fewer abortions could mean more babies – many of them born to mothers who are poor, unmarried and young, data shows.

Three-fourths of women who had abortions in 2014 were either poor or low-income, according to a survey by the Guttmacher Institute. The distinctions are based on federal poverty guidelines.

A more recent analysis published in 2020 found women who wanted an abortion but could not get one suffered greater economic hardships than women with access to the procedure, including increased debt, lower credit ratings and more negative financial events such as bankruptcy and eviction. These difficulties often lasted for several years after they were turned away by a clinic, according to the study.

Who gets an abortion in Ohio?

Gov. Mike DeWine released a video statement on the day Roe fell, suggesting that the state was ready to help.

“Ohio is already investing more than $1 billion to provide prenatal care, parenting classes, mentoring, education and nutrition assistance to pregnant mothers and their families,” he said. “But there's so much more to be done – so much work that remains. And so today I ask you, my fellow Ohioans, to work together with me to focus on these issues and commit ourselves to the health and success of Ohio families.”

Gov. Mike DeWine addresses Ohioans following the U.S. Supreme Court decision overturning Roe.

Gov. Mike DeWine addresses Ohioans following the U.S. Supreme Court decision overturning Roe.

DeWine said no matter where Ohioans stand on abortion, they should be able to come together on ways to support pregnant women, new moms and babies.

“While we may disagree vehemently on some things, we can still find common ground in other things,” DeWine said. “And so, let us now find that common ground, roll up our sleeves, dig deep, join together in solving the problems that we all agree must be solved.”

Children's coats hang along a wall inside Heartbeat of Toledo, where, as part of the nonprofit's Heart to Heart program, clients earn points as they participate in a free, two-year online prenatal and parenting curriculum. They can then redeem points in exchange for clothing, toys and other baby supplies.

Children's coats hang along a wall inside Heartbeat of Toledo, where, as part of the nonprofit's Heart to Heart program, clients earn points as they participate in a free, two-year online prenatal and parenting curriculum. They can then redeem points in exchange for clothing, toys and other baby supplies.

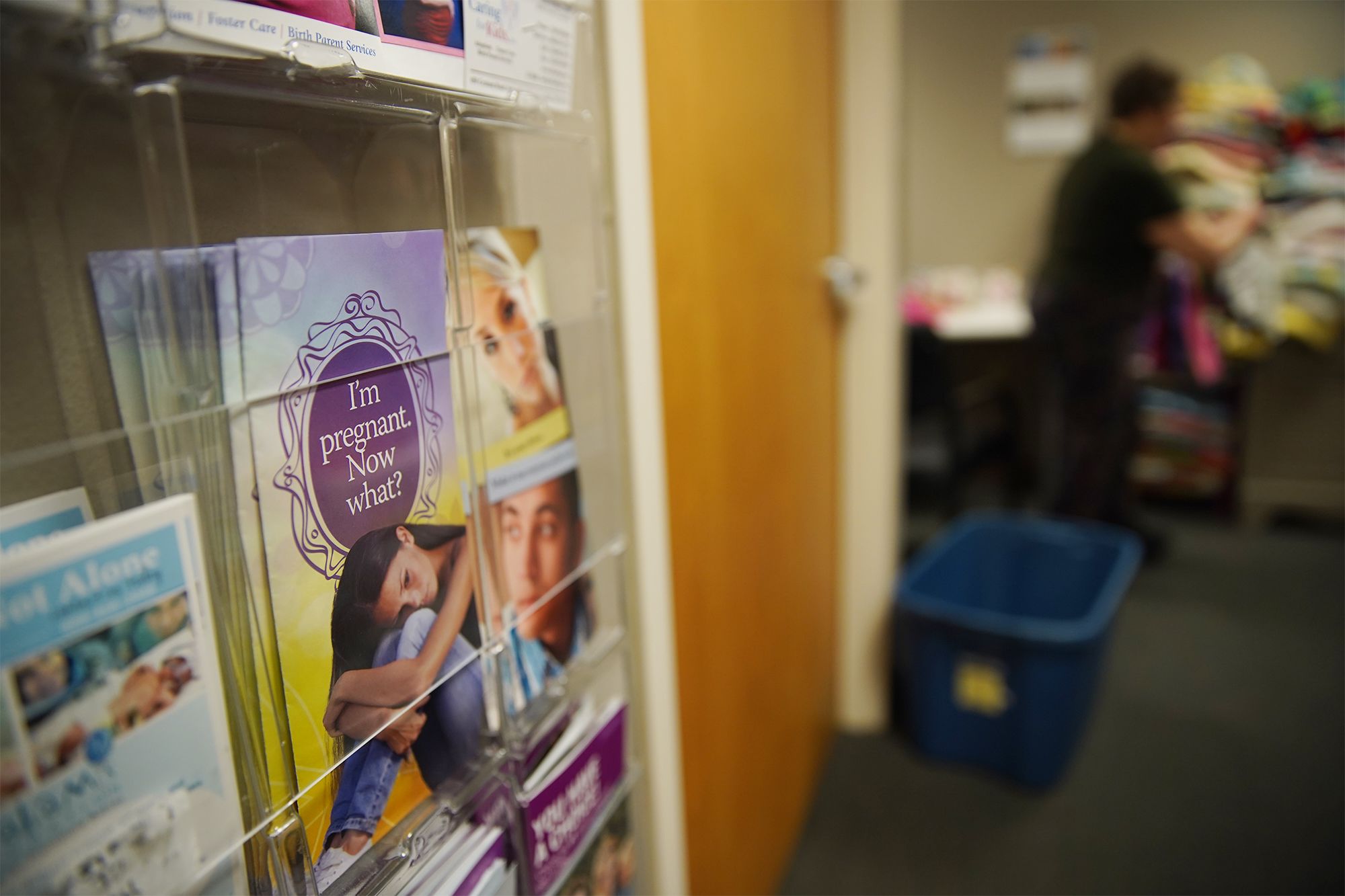

DeWine believes one solution is pregnancy centers. They are mostly nonprofit, faith-centered organizations that serve people who are, or think they may be, pregnant. They offer free pregnancy tests, ultrasounds and counseling. They also provide free parenting classes and baby supplies.

Since DeWine took office in 2019, he’s directed $15.3 million to pregnancy centers, according to the Ohio Office of Management and Budget. The Ohio legislature appropriated an additional $3 million in December.

The governor praised pregnancy centers during an appearance on The Bill Cunningham Show on 700 WLW in Cincinnati.

“They're in every part of the state. There's over a hundred of them,” he said. “They're doing the Lord's work by reaching out and sometimes becoming parents or becoming friends of people who come in there and just giving them help and assistance. So, these are all things that I think, Bill, we all should be able to agree on!”

But people don’t agree on pregnancy centers. Like most everything about abortion in America, they’re controversial. Pregnancy centers have a “shady, harmful agenda,” says Planned Parenthood. The Guttmacher Institute calls them a “public health concern.”

Heartbeat of Toledo volunteer Barbara Kunkel sorts through children's clothes.

Heartbeat of Toledo volunteer Barbara Kunkel sorts through children's clothes.

Pregnancy centers would disagree. Their websites state they are there to listen to women with unplanned pregnancies, offer them support and guide them to resources that may help them make an informed decision about what to do next.

Gina Bonino, executive director of Heartbeat of Toledo, a pregnancy center, said her staff provides services that include free pregnancy tests, ultrasounds and what she calls “options counseling.” She said they strive to be a safe, nonjudgmental space.

The ambiance at Heartbeat of Toledo was more like a therapist’s office than a doctor’s office. The walls were a chocolate brown. The lighting was soft. There was a large, black leather sofa. In the background was the sound of waves on a beach from a small, white sound machine in the corner of the room.

“From the moment they walk in the doors, we want them to get that sense of calm,” said Bonino. It’s “an escape from all the outside stressors and influences and just come, be a place of safety where they can just … be.”

A bin overflows with bottle and sippy cup parts.

A bin overflows with bottle and sippy cup parts.

Boxes of diapers donated by a Toledo-area business fill a room at Heartbeat of Toledo.

Boxes of diapers donated by a Toledo-area business fill a room at Heartbeat of Toledo.

Heartbeat of Toledo client Brianna Groch shops for clothes and other items in the nonprofit's Heart to Heart program boutique.

Heartbeat of Toledo client Brianna Groch shops for clothes and other items in the nonprofit's Heart to Heart program boutique.

Heartbeat of Toledo was founded in 1971, before abortion became legal nationwide in 1973. Heartbeat International, the group with which the Toledo center is affiliated, is now a global nonprofit with 3,000 affiliates. Its website says its programs are consistent with biblical and orthodox Christian ethics and teachings.

Still, Bonino said they steer clear of anything overtly religious, like Bibles in the waiting room.

“We are not a religious organization,” she said. “We are not a political organization. So we stay away from anything that would lead clients to think that.”

Bonino said pregnant girls and women who come to them seeking help for their unplanned pregnancies are told about their options: abortion, adoption and parenting.

“It’s not just a decision on whether I want to keep this baby or not, whether I want to be a mom or not. It's so much more,” she said. “It’s the relationship that I'm in or finances or it's daycare or it's ‘I'm living in my car’ and it's a housing issue. So, can we connect you with food banks? Can we connect you with housing and things that are outside of our walls that may help you make this decision?”

Bonino said her staff does not coerce a woman into making a choice. She knows that’s not what some people might think.

“Everyone makes their assumptions and groups people together,” she said. “But we are really adamant about that. You know, letting the women know we are here to support you. At the end of the day, it’s your decision.”

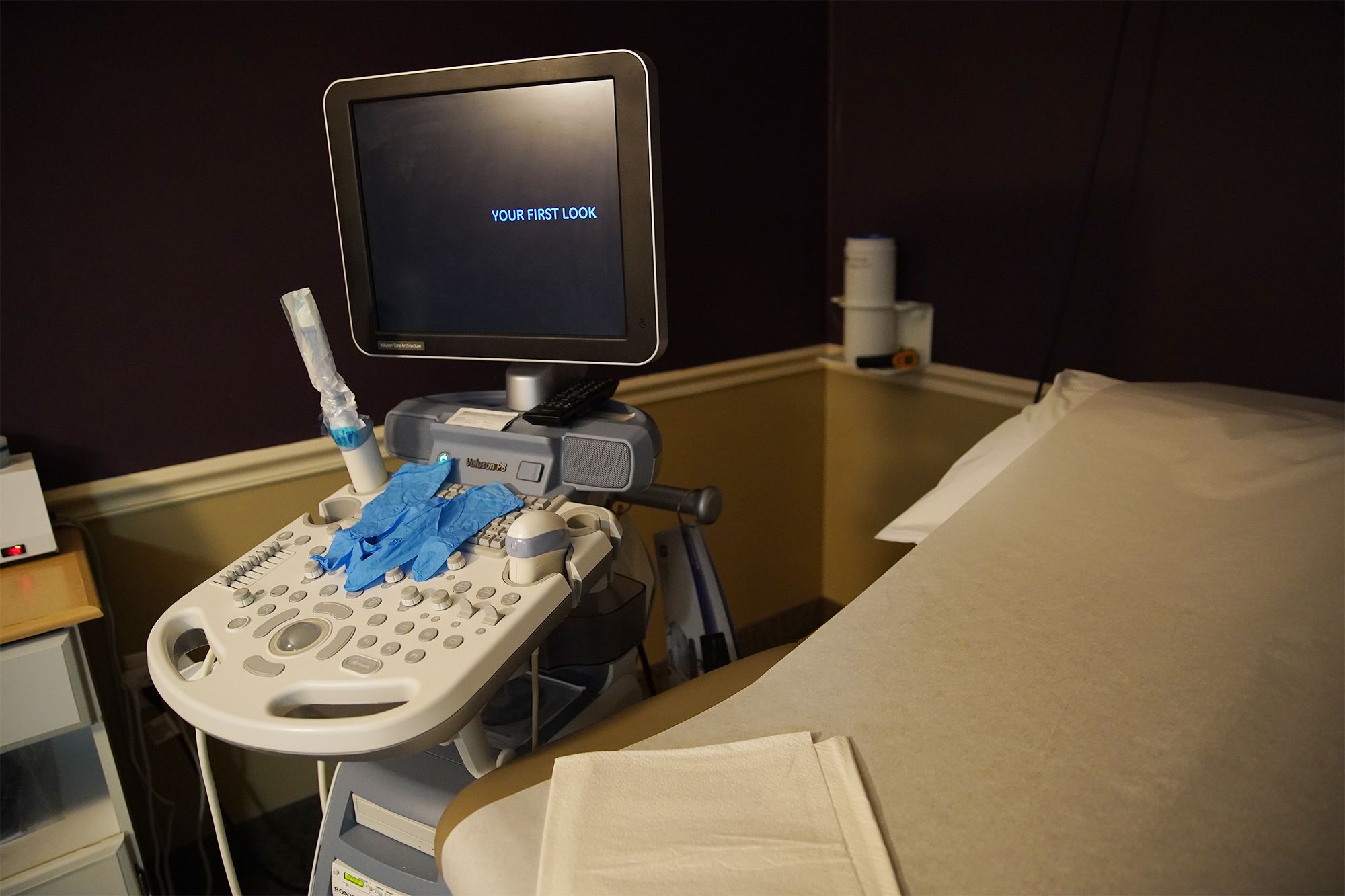

After counseling comes the free ultrasound.

“The ultrasound tends to be the most emotional part of the appointment,” Bonino said. “That's where things really get real.”

Anti-abortion advocates put great stock in ultrasounds. Organizations like Knights of Columbus, a Roman Catholic service organization, and Physicians for Life say a woman is less likely to get an abortion after seeing her developing baby.

It’s why some states, including Ohio, require abortion clinics to offer a patient the opportunity to see the ultrasound before the procedure.

On its website, Heartbeat of Toledo offers information about the different types of abortion procedures and possible side effects and risks, but it states it does not provide abortion or abortion referrals. Some critics of pregnancy centers say they mislead women into thinking they will help them get an abortion.

Heartbeat of Toledo’s website also has a list of staff that includes registered nurses, licensed social workers and certified sonographers.

Bonino said they use these credentialed workers to counter critics who call pregnancy centers “fake clinics.”

In its 2020 annual report, Heartbeat of Toledo said nearly all of its clients chose not to have an abortion.

“If you're talking about the best possible outcome, what is most celebrated? It's that life, it’s that mom choosing life because she wants to,” Bonino said. “But at the end of the day, no matter what she decides, you know, it is her option. No judgment to her.”

The center strives to make women feel comfortable and in control, Bonino said. But that effort was undermined while the Heartbeat Law was in force.

“What we are seeing now is more panic,” she said. “Whereas before we may have seen a client who is exploring her options, and she feels she has time to explore her options. Now there's this pressure to, ‘I have to hurry up and make this decision before that six-week mark.’”

Bonino said the pressure that the six-week legal limit put on pregnant people did not surprise her.

“It's something that saddens me because this overturn has been celebrated by so many. But I am seeing the other side of it,” she said. “And it's devastating.”

“It's devastating because women are rushing into a decision and not taking the time to consider all of their options.”

Bonino said she wants her clients to take their time.

“Just reminding women every state is different,” she said, noting that women past Ohio’s six-week limit could seek legal abortions in other states. “You have time. They do, they have time. Because a well-thought-out, well-informed decision has a lower risk of being regretted than something I rush into based on a situational stressor.”

Gina Bonino is the executive director of Heartbeat of Toledo.

Gina Bonino is the executive director of Heartbeat of Toledo.

The words "Your first look" move across the screen of an ultrasound machine at Heartbeat of Toledo.

The words "Your first look" move across the screen of an ultrasound machine at Heartbeat of Toledo.

Heartbeat of Toledo volunteer Melinda Meeks sorts donations.

Heartbeat of Toledo volunteer Melinda Meeks sorts donations.

Heartbeat of Toledo client Brianna Groch smiles as she interacts with her infant son Raiden at the nonprofit's Heart to Heart program boutique.

Heartbeat of Toledo client Brianna Groch smiles as she interacts with her infant son Raiden at the nonprofit's Heart to Heart program boutique.

Bonino herself was drawn to this work because of her experience with unplanned pregnancies.

Bonino, who is 36, first became pregnant at 19. Abortion, she said, never entered her mind. She had two more children. Then a fourth, with a new partner.

Then she became pregnant again, with twins. Her partner didn’t want six children. She had a choice: Get an abortion or raise six kids by herself.

She said she ran the numbers and looked at what housing she could afford that would accommodate her and her six kids.

“Looking at a couple of places and there are bars on the window. I saw two drug deals go down. I was like, ‘What environment would I have to put my other four children in to keep these two?’” she said.

Bonino opted to get an abortion.

“And that was the hardest thing I've ever had to go through in my life,” she said, tearing up.

“It wasn't that I didn't know what I was doing. It's not that I didn't know the value of life. I knew. And that’s what made it so hard,” she said. “I felt, in that moment, I was doing what was best for those four children to follow through.”

Bonino said she worries other women may choose abortion, as she said she did, out of fear: fear of disapproval, fear of abandoning educational or career goals, fear of parenting, fear of financial insecurity.

Heartbeat of Toledo tries to address those concerns, Bonino said. If women decide to bring their pregnancies to term, the center can provide emotional and material support, according to Bonino. It offers maternity clothes, diapers, wipes, formula, cribs and other supplies for children from infancy to age 2. Clients earn these items by taking free parenting classes.

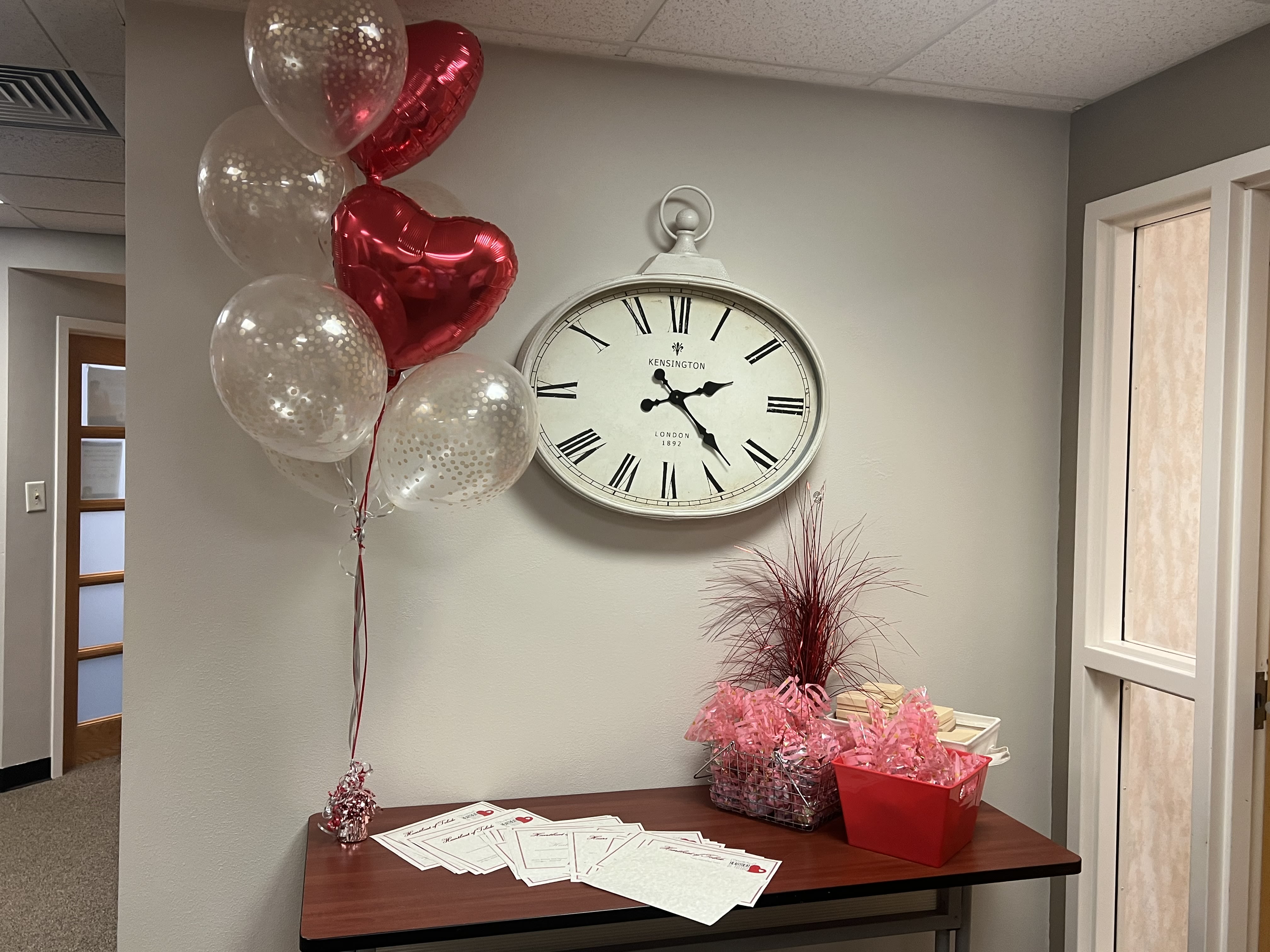

Last year, 43 clients completed the two-year parenting course. The center threw a graduation party. There was cake, heart-shaped balloons and graduation certificates.

Heart-shaped balloons, cellophane-wrapped party favors and graduation certificates await graduates of Heartbeat of Toledo’s two-year parenting course on Aug. 26, 2022. Clients take the free course to earn points for maternity and baby clothes, strollers and other baby supplies. [Amy Eddings / Ideastream Public Media]

Heart-shaped balloons, cellophane-wrapped party favors and graduation certificates await graduates of Heartbeat of Toledo’s two-year parenting course on Aug. 26, 2022. Clients take the free course to earn points for maternity and baby clothes, strollers and other baby supplies. [Amy Eddings / Ideastream Public Media]

Celestine Allen was there with her 2-year-old daughter. Allen said she did not come to Heartbeat of Toledo for pregnancy counseling. She was eight weeks pregnant when she signed up for the class and the free supplies.

She said she’d recommend the class to a friend.

“Especially if they can't really afford much of anything for their baby,” she said. “Take the class, you get cool stuff.”

Celestine Allen, 42, holds her two-year-old daughter, Margaret, during a ceremony on Aug. 26, 2022, for graduates of Heartbeat of Toledo’s two-year parenting course. Allen said she did not come to the pregnancy center seeking help in making a decision about her pregnancy. She said she was interested in the free baby supplies. [Amy Eddings / Ideastream Public Media]

Celestine Allen, 42, holds her two-year-old daughter, Margaret, during a ceremony on Aug. 26, 2022, for graduates of Heartbeat of Toledo’s two-year parenting course. Allen said she did not come to the pregnancy center seeking help in making a decision about her pregnancy. She said she was interested in the free baby supplies. [Amy Eddings / Ideastream Public Media]

Another graduate, Hayley Jones, a mother of six children under 7, said she never considered abortion when she came to the center.

“I wouldn't say there was any concerns – just trying to find some local resources,” she said.

Pregnancy centers are not just dealing with pregnancies, experts say. They’re dealing with poverty.

Heartbeat of Toledo holds a graduation ceremony on Aug. 26, 2022, for 43 clients who participated in its two-year "Heart to Heart" parenting course. There were boxes of mini-Bundt cakes, a red tub of potato chips and a tray of raw vegetables with dip. [Amy Eddings / Ideastream Public Media]

Heartbeat of Toledo holds a graduation ceremony on Aug. 26, 2022, for 43 clients who participated in its two-year "Heart to Heart" parenting course. There were boxes of mini-Bundt cakes, a red tub of potato chips and a tray of raw vegetables with dip. [Amy Eddings / Ideastream Public Media]

Material support is a big part of what these centers do, said sociologist Alexandra Kissling, lead author of a recent study of the services offered by what she calls crisis pregnancy centers. She spent time at eight centers in Ohio.

“They really didn't do very much of what they called ‘options counseling,’” Kissling said. “In fact, some of the people who work there craved that. They felt that ‘This is what I actually got into this service to do, is to talk to people about abortion.’”

Kissling said the material support provided by pregnancy centers is short term.

“It comes with strings. It can also come with a strong religious quality to it as well. Many of the CPCs that I researched offered Bible study as a way to purchase the material goods needed, like diapers,” she said. “I feel like that is deeply problematic for the state to be providing money to organizations that have an anti-abortion and an explicitly religious bent to them.”

Researchers have found some pregnancy centers make false or misleading claims about abortion risks, according to Kissling’s findings, published in the international journal, “Culture, Health & Sexuality” in September 2022.

“Some CPCs have been set up near abortion clinics with the intention to divert potential abortion clients to delay care, which risks people’s health,” the article states. “CPCs may also provide medically inaccurate information, including alleging false links between abortion and risk of breast cancer, mental health issues, and infertility, as well as overestimating the risk of miscarriage among individuals with a recognised pregnancy, to dissuade clients from seeking an abortion immediately.”

Rev. Terry Williams, the pastor of Orchard Hill United Church of Christ in Chillicothe and an abortion rights advocate, said he has counseled people who felt manipulated and abused after working with a CPC.

“Frankly, I end up counseling a lot of people who, a year or two or three years after interacting with a crisis pregnancy center, now have children that they cannot take care of because these people made this sound like it was going to be such an easy choice to parent a child,” Williams said. “And now they've disappeared from their lives.”

The state should take the money it spends on pregnancy centers and invest it in maternal healthcare services, birth control subsidies and rural health equity initiatives, Williams said.

Others say it should go to community health clinics or to increase welfare benefits.

The debate over resources misses a larger point, said Kellie Copeland, the executive director of Pro-Choice Ohio, an abortion rights advocacy group.

“All the social services in the world are not a substitute for abortion access,” she said at a strategy meeting with doctors, clinic operators and reproductive activists last July. “Some people just simply cannot handle bringing a child into this world for lots of very good reasons.”

Despite the concerns about pregnancy centers, they stand to get more taxpayer money in the near future. Gov. DeWine and conservative lawmakers see pregnancy centers as partners in the state’s effort to meet what many believe will be a growing demand for help.

Next:

Observers of the Ohio Legislature think the state’s abortion restrictions have less to do with following the will of the people than with legislative gerrymandering and partisan redistricting that give a political party a lot of power.

More in Chapter 3: “The Fight Here in Ohio is Just Beginning.”