In prison, they wrote poetry to maintain a sense of freedom. Beyond bars, writing continues to guide them.

Produced by Justin Glanville, Ideastream Public Media

Featuring poets from the ID13 Prison Literacy Project

Sam Stokes

"My favorite line was 'I'm playing the cards that I was dealt.' When in all actuality, I threw my hand in and I picked my cards myself. 'Cause contrary to popular belief I was never a dude who had to be in the streets."

Listen to Sam Stokes' story.

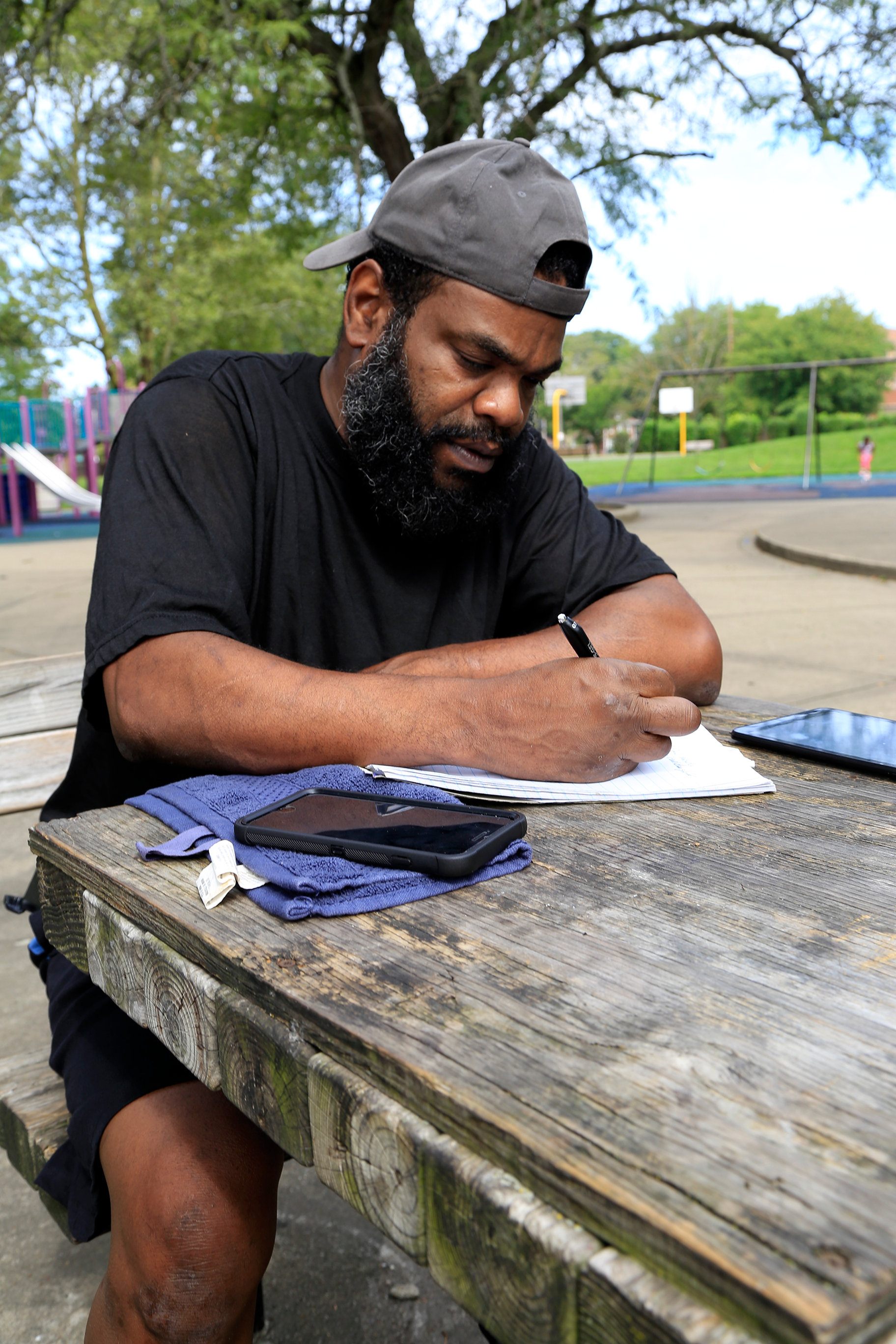

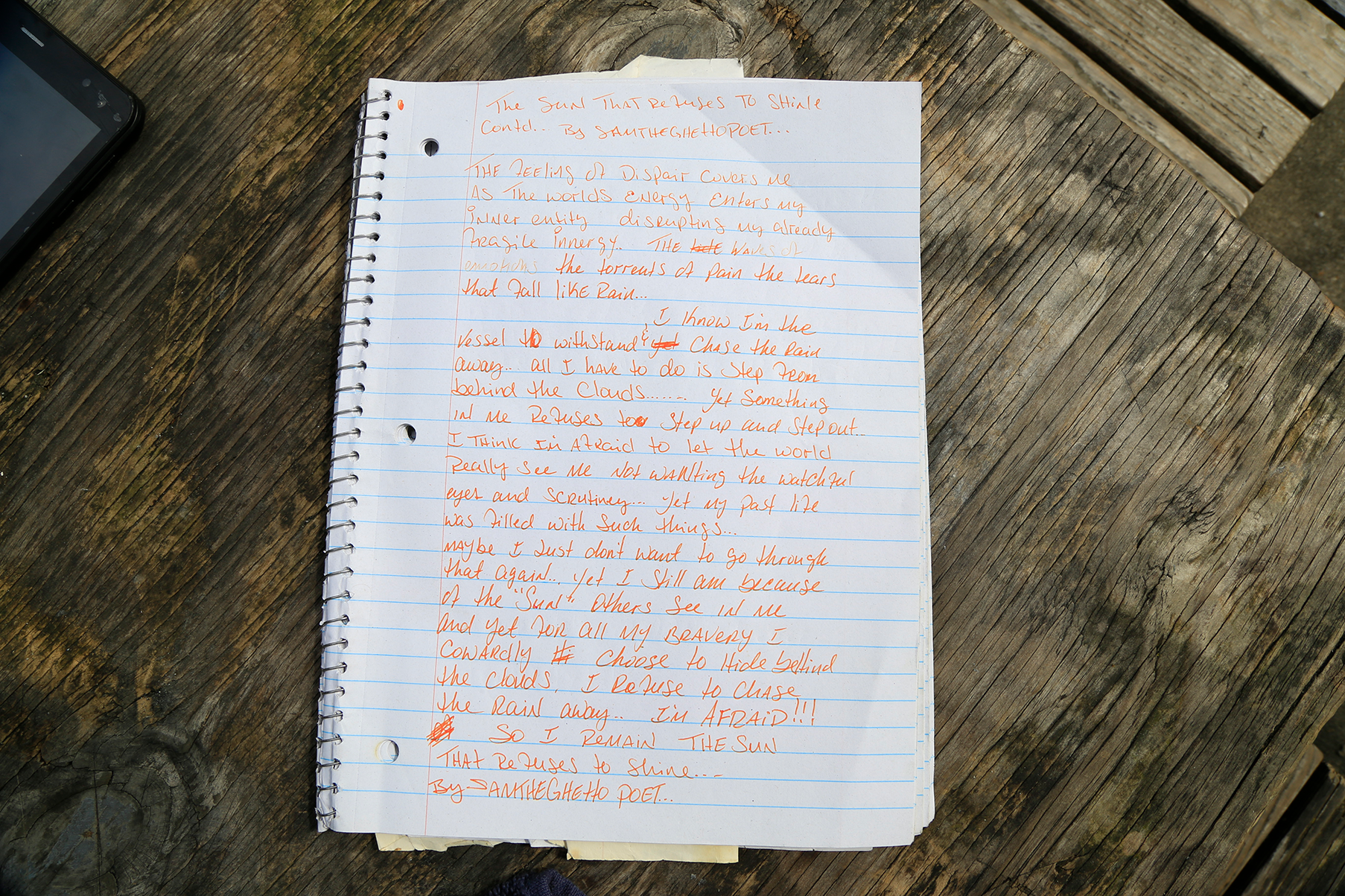

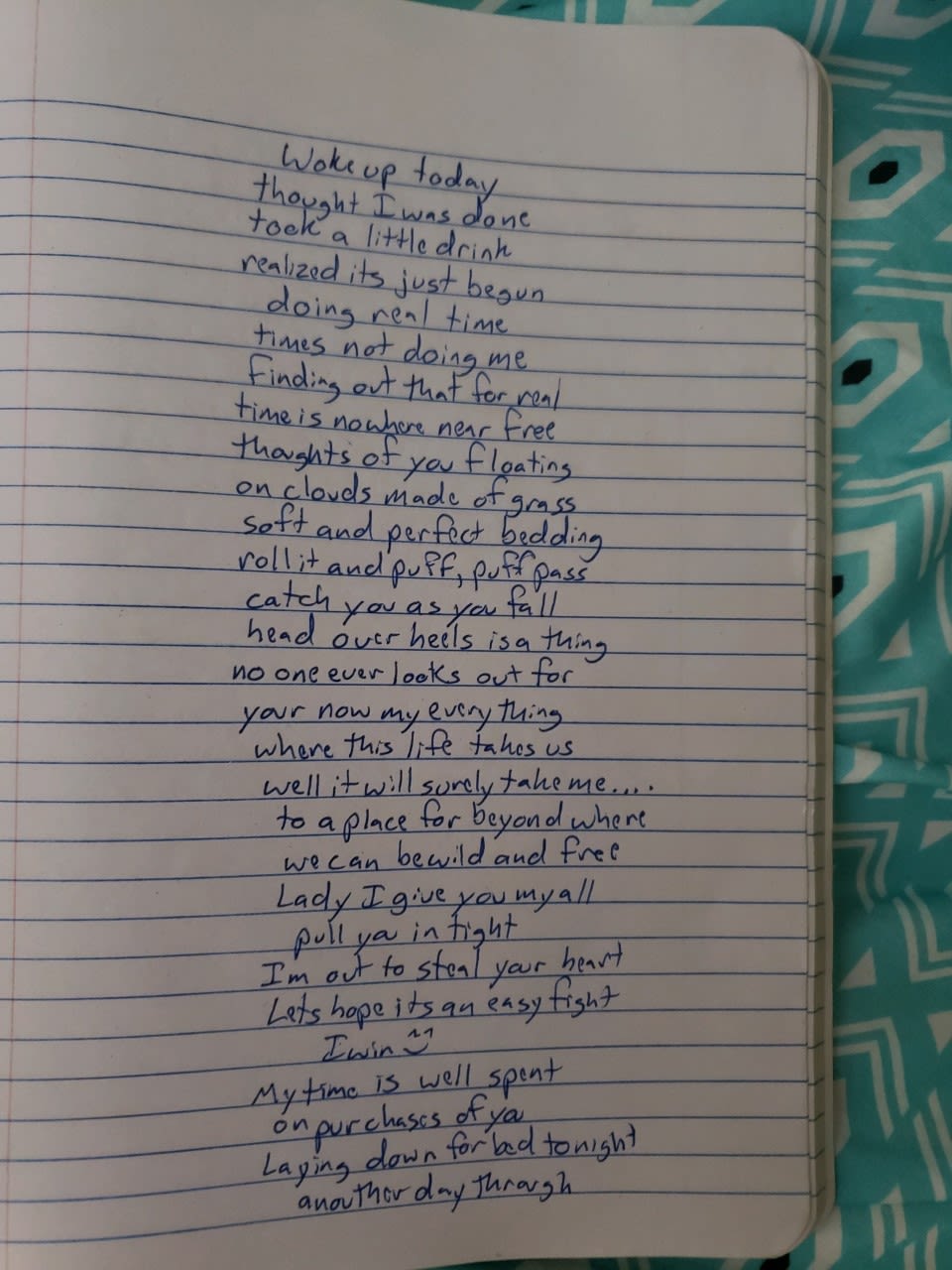

Sam Stokes had barely written a word of poetry until one night in his prison cell, as much out of frustration as inspiration, he picked up a notebook and a pencil.

"I just wrote down how I felt about the situation," Stokes remembered.

From there, he kept going.

"It became an outlet for me to be able to express things that I felt like I couldn't say or I shouldn't say as a man, as a person," he said.

Many of his early poems were a way to unpack what drew him to become involved in street violence in his youth. Stokes spent about 20 non-continguous years incarcerated, starting when he was 10.

"My growing up wasn't a bad growing up," said Stokes, now 49. "I was adopted by two people that were wonderful. My father worked for the East Ohio Gas Company. My mother started her own daycare business. Like I say in one of my poems, I was never a dude that had to be in the streets, but I was looking for friends, for brotherhood."

He's now been free for about 10 years, and — as pandemic restrictions allow — he reads his poetry in neighborhood bars on Cleveland's East Side, where he lives, and at Captiv8, a downtown bar where he's a regular performer. His stage name is Sam The Ghetto Poet.

"I see (performing) as not just making a change in my life, but hopefully making change in others' lives, too, by being able to relate to some of the things I've been through," he said. "Writing poetry doesn't have to be lucrative, but it sustains my soul."

Bonus: Watch Sam recite his poem "The Sun That Refuses To Shine."

Wesley Dirmeyer

"Poetry made me more of an open person. I can talk a little more to people about stuff that I'm feeling, which is hard to do as a guy."

Listen to Wesley Dirmeyer's story.

[photo: Justin Glanville / Ideastream Public Media]

[photo: Justin Glanville / Ideastream Public Media]

Growing up, Wesley Dirmeyer read more than a lot of his friends, but he started living and breathing books once he went to prison.

In the five and a half years he was incarcerated at Lake Erie Correctional Institution, he estimates he read at least 1,000 books — many of them checked out of the prison library, where he also worked.

Reading, in turn, pushed him toward writing.

"I would write small things here and there and and some people liked my stuff," Dirmeyer said. "So I just started writing a little more and trying to put more of myself into it."

Many of his poems dealt with troubled relationships from his past; others touched on his struggles with addiction. But even though the material was dark, writing left him with a feeling of lightness.

"Poetry made me more of an open person," he said. "I can talk a little more to people about stuff that I'm feeling, which is hard to do as a guy. It was a doorway — like, you open the door and you can let some stuff out."

Soon after being released in 2018, Dirmeyer got a job driving a truck. He delivers frozen foods and supplies to restaurants.

He still buys books with the intention of reading them, but with family and work obligations he rarely has time to read or write.

"I miss it," he said. "But at the same time — I don't."

Bonus: Watch Wesley recite his poem "Silence."

[photo: Wesley Dirmeyer]

[photo: Wesley Dirmeyer]

Da'Jon Carouthers

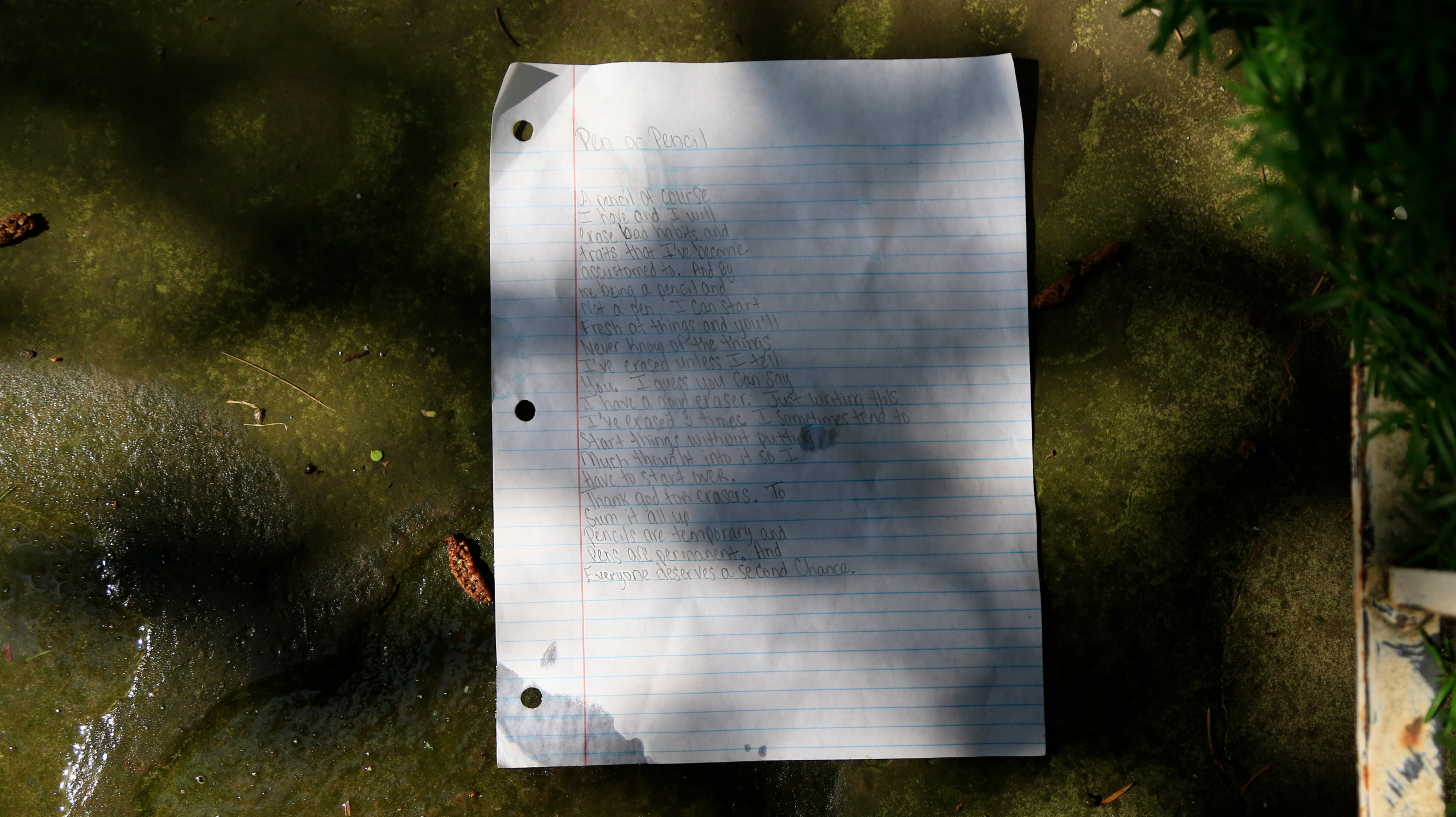

"By me being a pencil and not a pen, I can start fresh at things and you'll never know of the things I erase unless I tell you."

Listen to Da'Jon Carouthers' story.

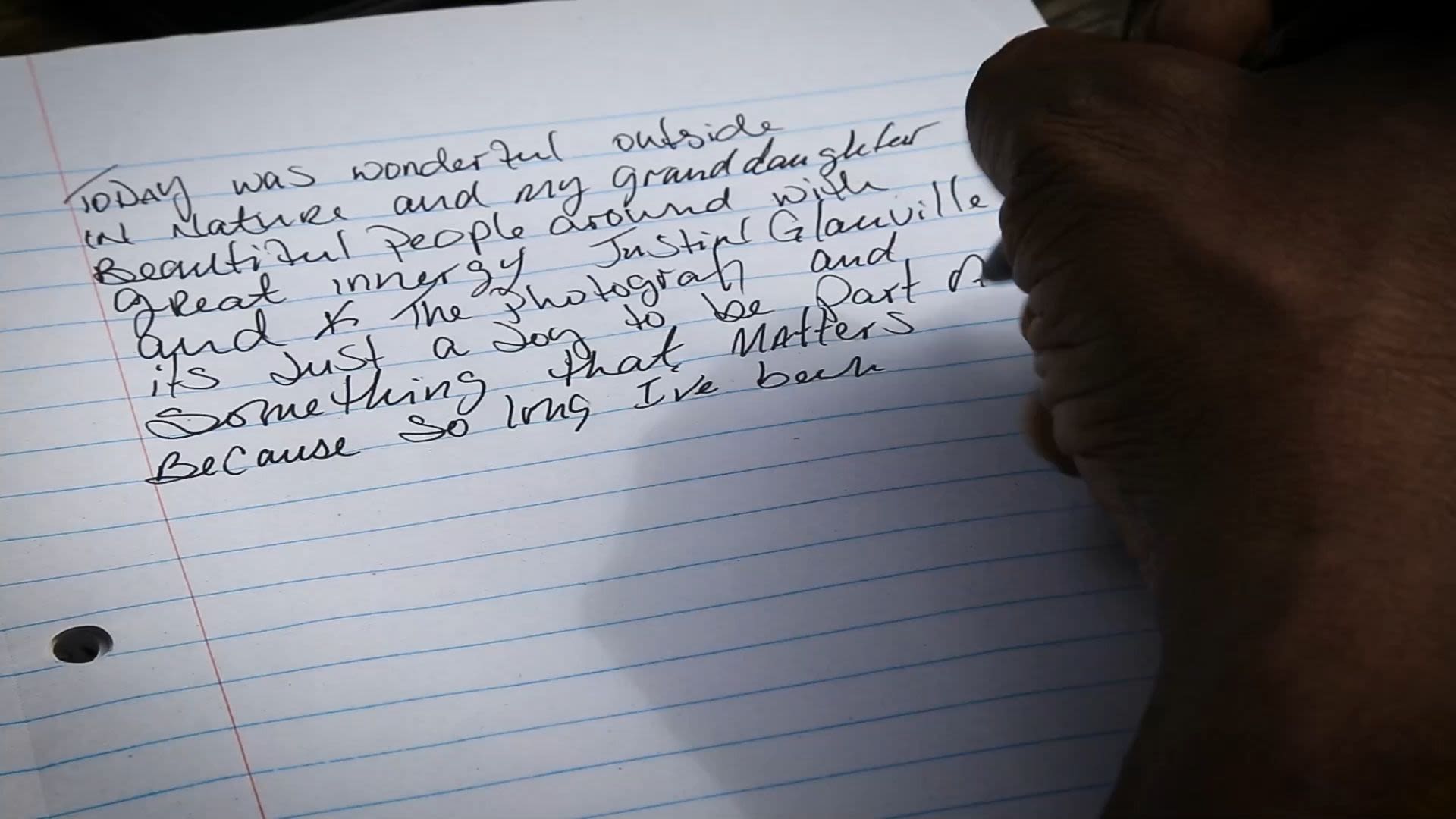

For Da'Jon Carouthers, the biggest contrast between free life and incarcerated life is the noise.

"It's never really quiet," Carouthers said. "Even at night when you're sleeping, you've got two people to your right, two people to your left — you have no space."

He began writing poetry and fiction as a way of creating that space for himself.

"Sometimes I'd go to the library and I'd put my headphones on," he remembered. "The next thing you know, I look up and it's three hours later and I wrote a whole chapter and imagined the next three chapters."

Writing also helped him imagine a different life, he said, helping keep his mind focused on life outside prison bars. He eventually applied for, and was granted, early release through the Cuyahoga County Reentry Court.

Carouthers published his first novel, The Cross You Bear, shortly after his release. He wrote the first draft — all long-hand — while incarcerated.

He also continues to write poetry. His most recent piece was about his mother, who passed away in January.

"It's still therapeutic for me," he said.

Bonus: Watch Da'Jon recite his poem "Pen or Pencil."

Jonathan Young

"Putting my feelings on paper, I started to learn a lot about who I actually was, so I didn't have to portray a character. I didn't have to pretend to be somebody that I wasn't when I got out."

Listen to Jonathan Young's story.

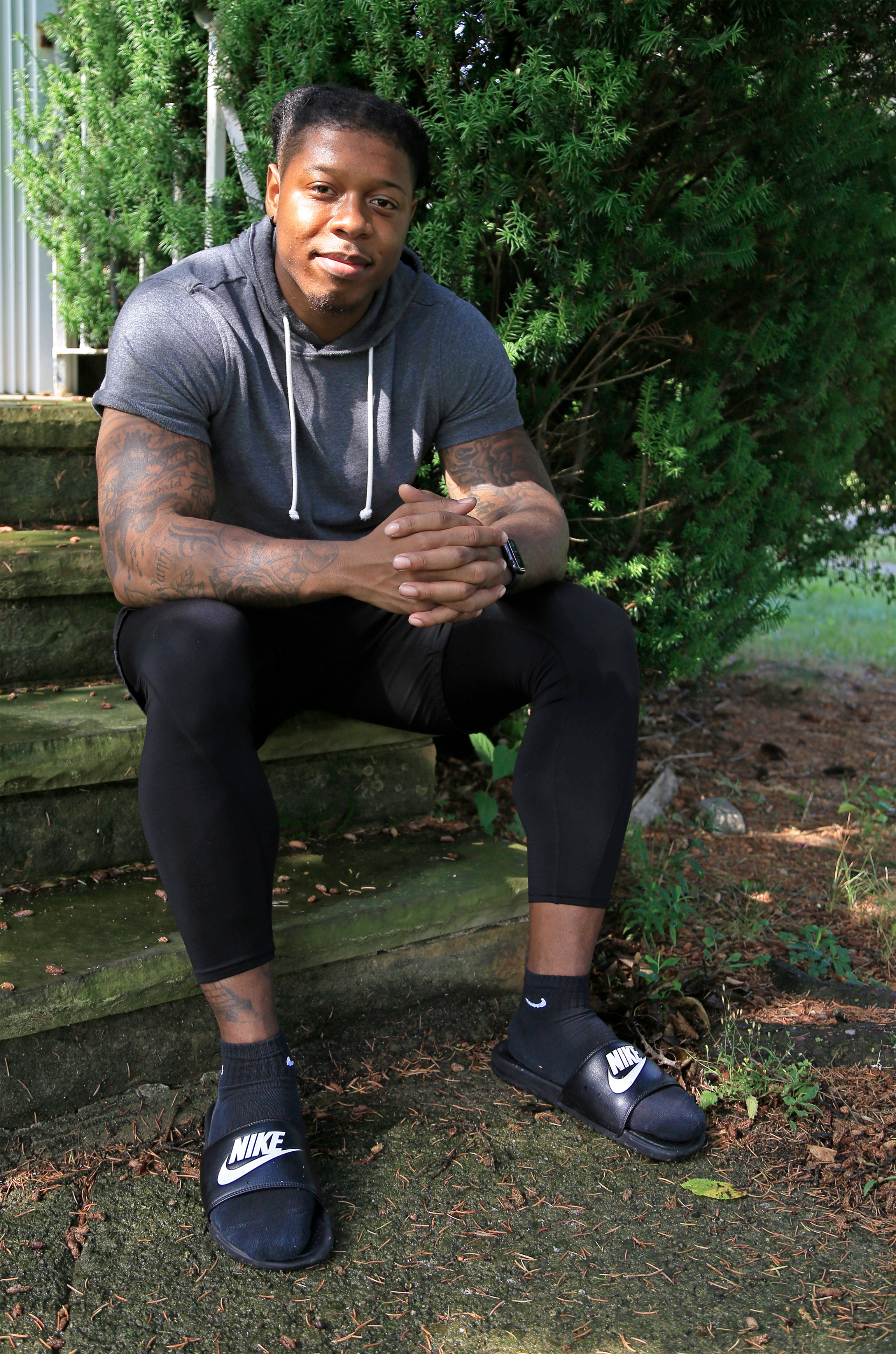

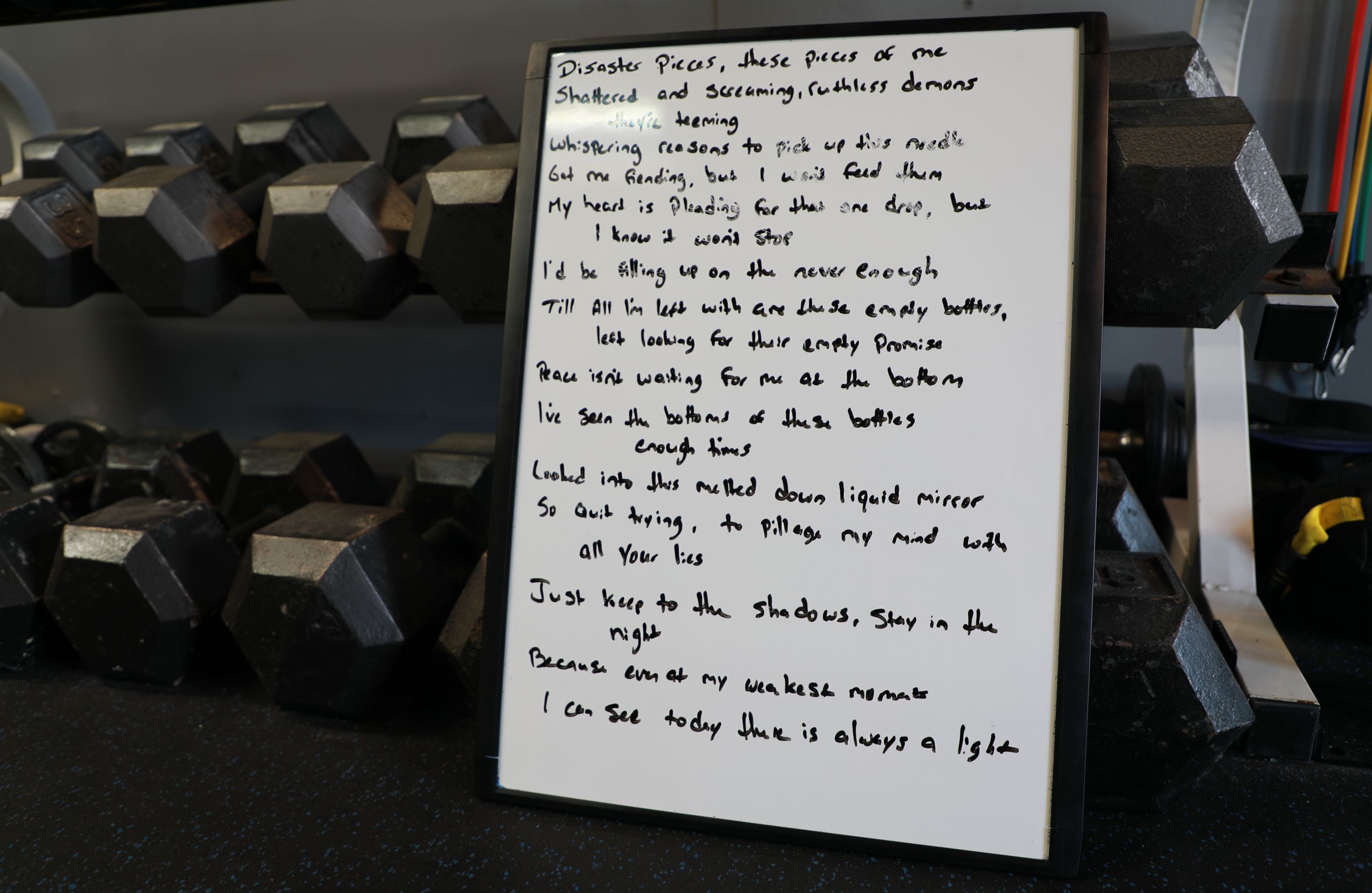

Before Jonathan Young began writing poetry through the ID13 Prison Literacy Project, he spent a long time trying to "fit in" with others around him.

"I took on a character — really uncommunicative, tough enough not to be messed with — that wasn't really me, but it helped me survive," Young said.

He'd been incarcerated for robbing in connection with a heroin addiction. Eventually, as he weaned off the drug, he began to take an interest in more positive pursuits.

Eventually, I just got tired of being angry and depressed," Young said. "I started working in the library there, and then started getting involved with some of the programs," including ID13.

That was when he truly began to see to the other side of imprisonment, he said.

"Putting my feelings on paper, I started to learn a lot about who I actually was, so I didn't have to portray a character," Young said. "I didn't have to, you know, pretend to be somebody that I wasn't when I got out."

He now works as a personal trainer, and recently started his own gym: Rising Phoenix Transformations, in the Cleveland suburb of Northfield. He's also married and a father.

Bonus: Watch Jonathan Young recite his poem "Disaster Pieces."

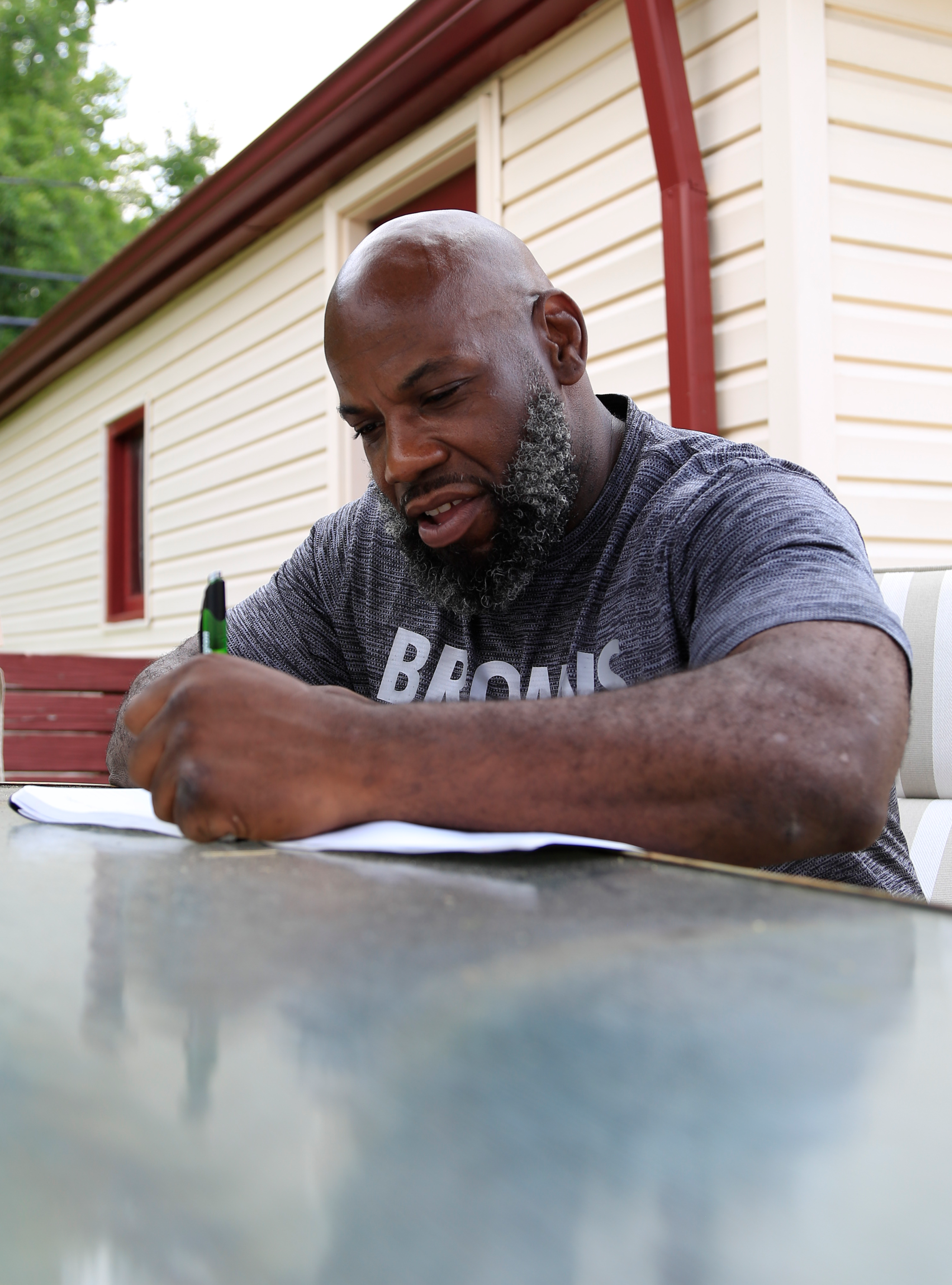

Cardell Belfoure

"Right now, I'm working for a roofing company.... Last year, I was behind a barbed-wire fence. This year I'm feeling like I'm on top of the world because I'm on this roof."

Listen to Cardell Belfoure's story and join him on a roofing job as he reads excerpts from his poem "Faith."

Cardell Belfoure had been writing poetry for several years before joining the ID13 Prison Literacy Project while incarcerated at Grafton Correctional Institution in Grafton, Ohio.

"Poetry, when I was locked up, was like therapy for me," Belfoure says. "In a space of incarceration, everybody's got their guard up. So with me with writing, now I can express myself."

Since his release in December 2020, Belfoure has been working as a roofer and runs a collective of Cleveland poets called Poetic Companions. He wants to organize readings both inside prisons and in urban communities where young men are at higher risk of incarceration.

"I wouldn't say poetry is why I have my freedom, but it's a nice part of my freedom ," Befoure says. "It's given me a cause. I want to be a beacon of light and help people understand that what you have is precious, which is your freedom."

He lives with family in Warrensville Heights.

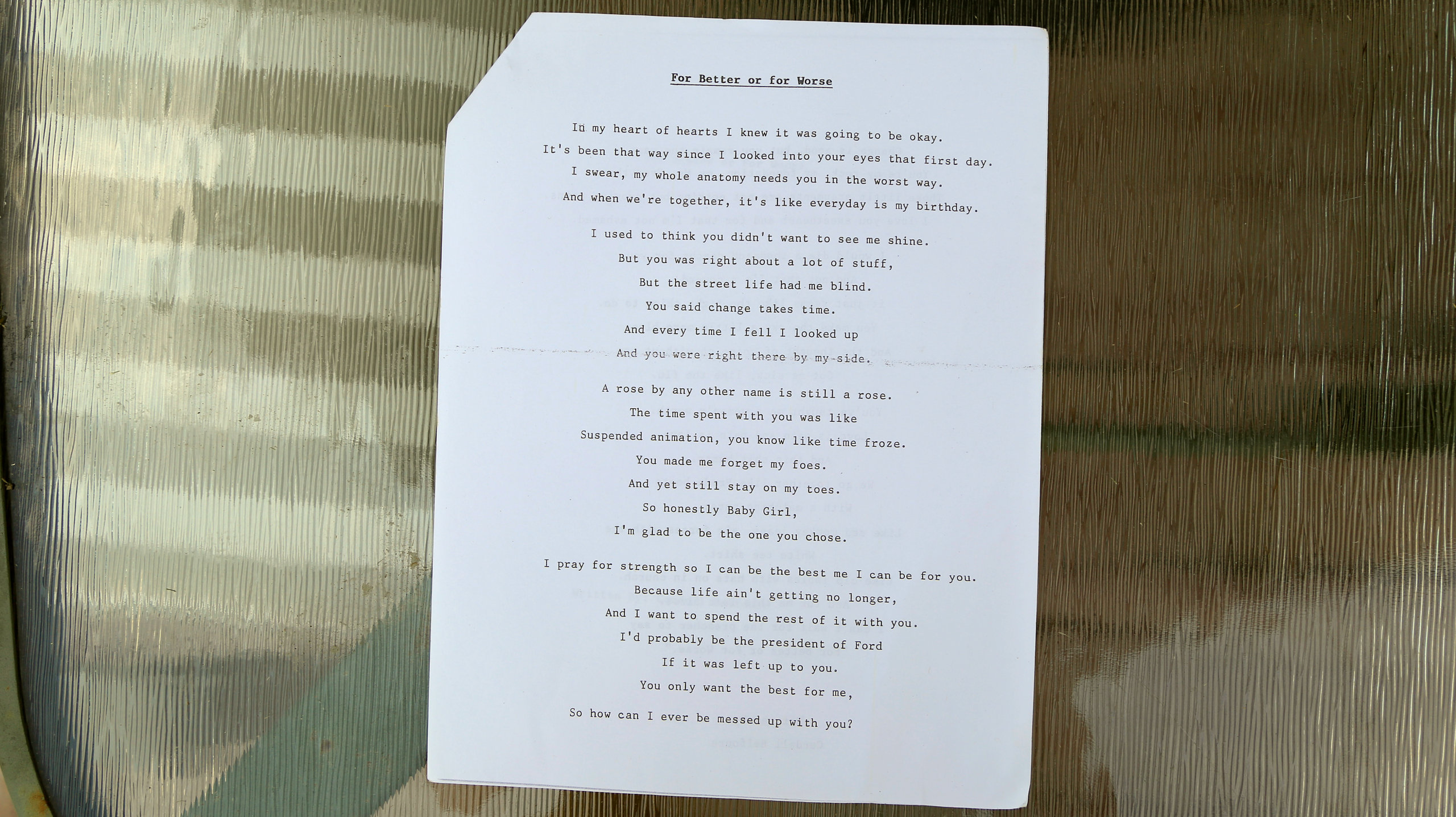

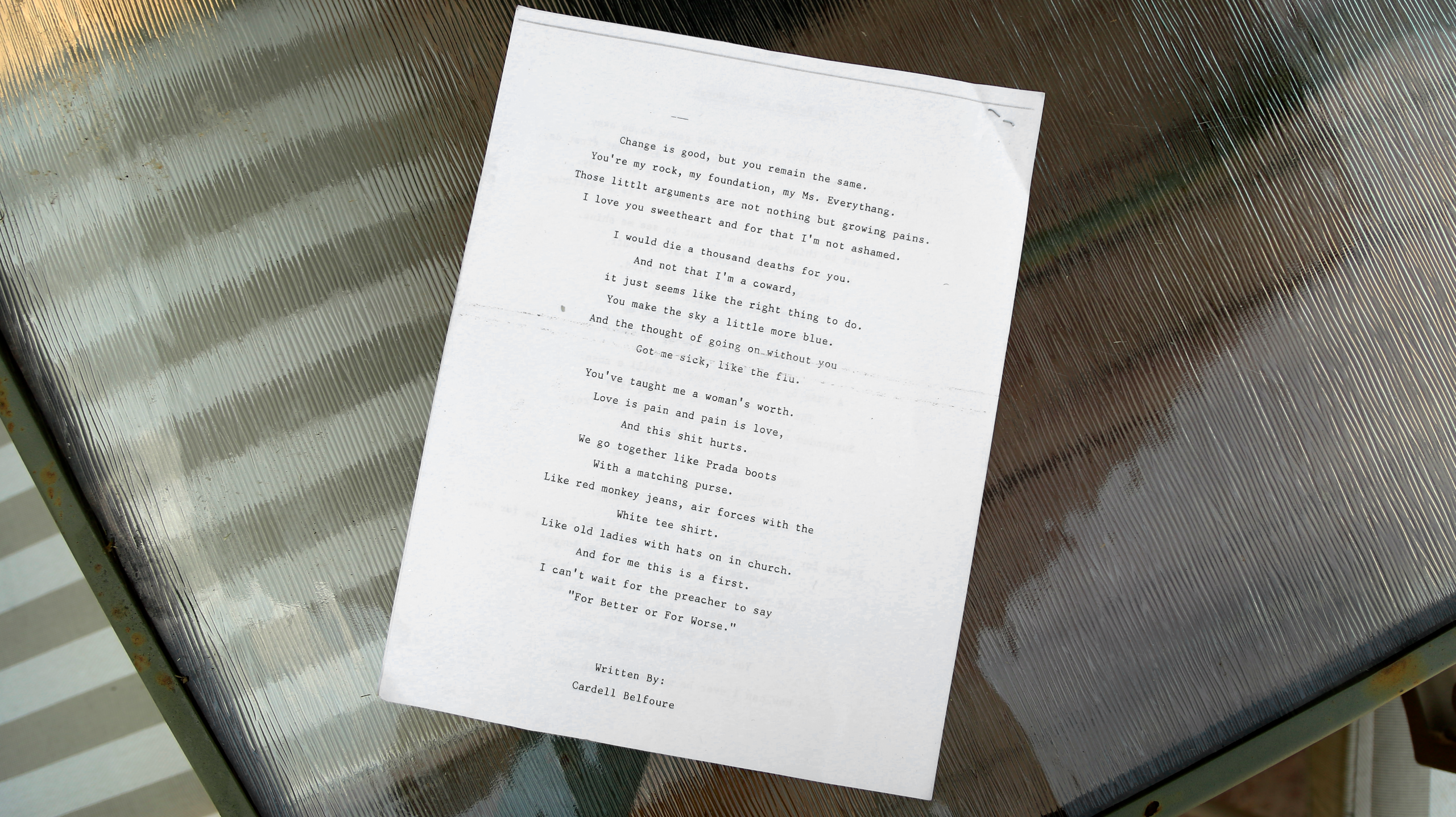

Bonus: Watch Cardell recite his poem "For Better or For Worse."

About Poetic Reentry

Poetic Reentry is a sound-rich series featuring formerly incarcerated men sharing poetry they wrote in prison, alongside reflections on their lives since release. Most of the men participated in the ID13 Prison Literacy Project, devoted to providing a voice, an outlet and a platform for incarcerated individuals at various correctional institutions in the state of Ohio.

Produced by Justin Glanville

Photography and web layout by Margaret Cavalier

Mike McIntyre, Executive Editor

Amy Cummings, Managing Producer of Programs and Specials

Mark Rosenberger, Chief Content Officer

Logo design by Pat Miller