Royal Influencers in the Time of Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven's journey from obscurity to fame through the support of his patrons

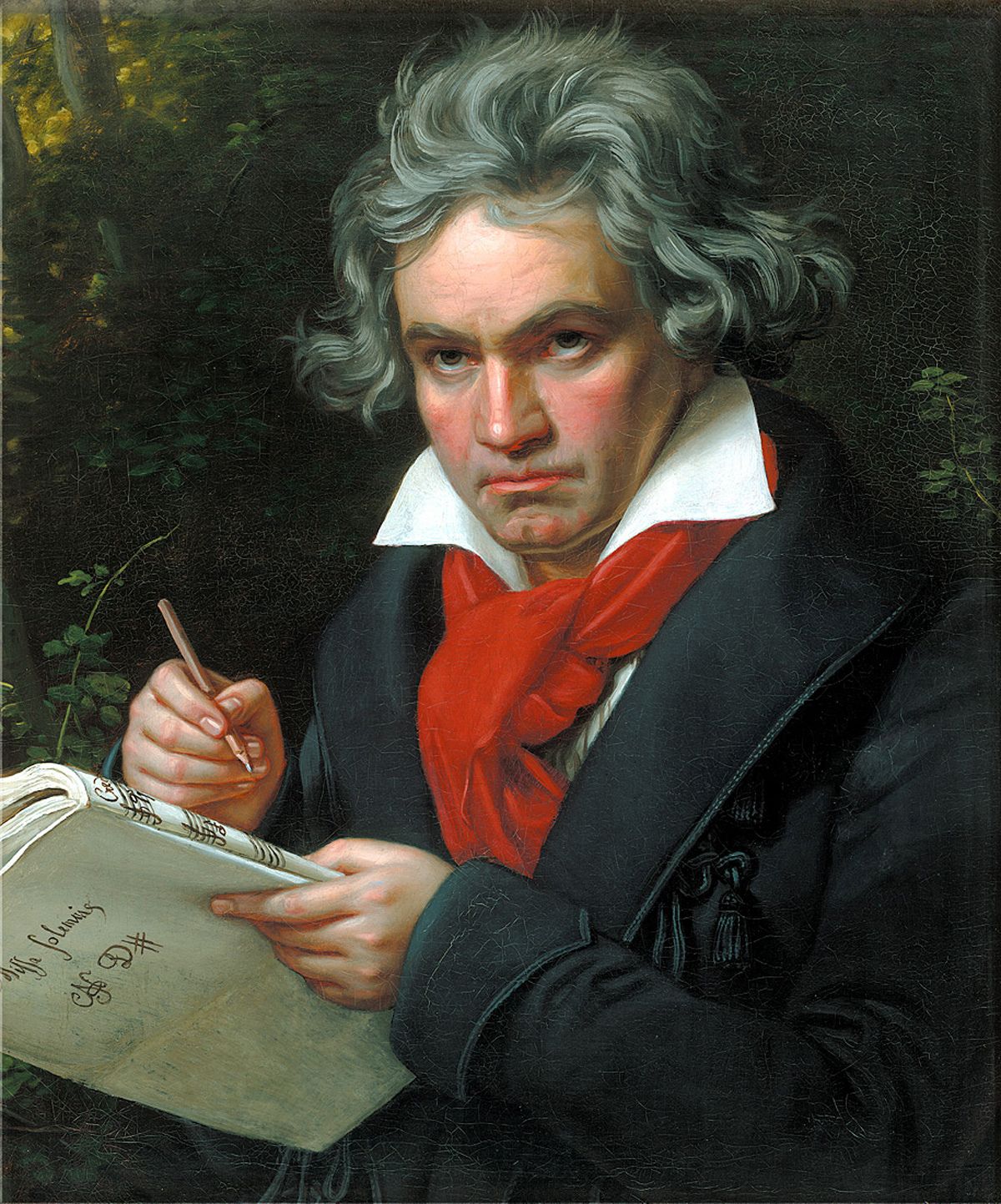

Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein, painted by Antonín Machek, retrieved from Wikipedia.

One was a Privy Councillor at Bonn and commander of the Teutonic Order, another was responsible for promoting the legacy of Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel in Vienna, and the other was an eccentric prince, described by Countess Lulu Thürheim as a “cynical degenerate and a shameless coward.” These three individuals – Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein, Baron Gottfried van Swieten, and Prince Karl Lichnowsky – share a unique connection. Through the patronage system of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, wealthy and influential individuals supported the work of composer Ludwig van Beethoven; as Beethoven journeyed from Bonn to Vienna, his connections to Waldstein, van Swieten, and Lichnowsky drew him from obscurity and propelled him to the tremendous acclaim he holds today.

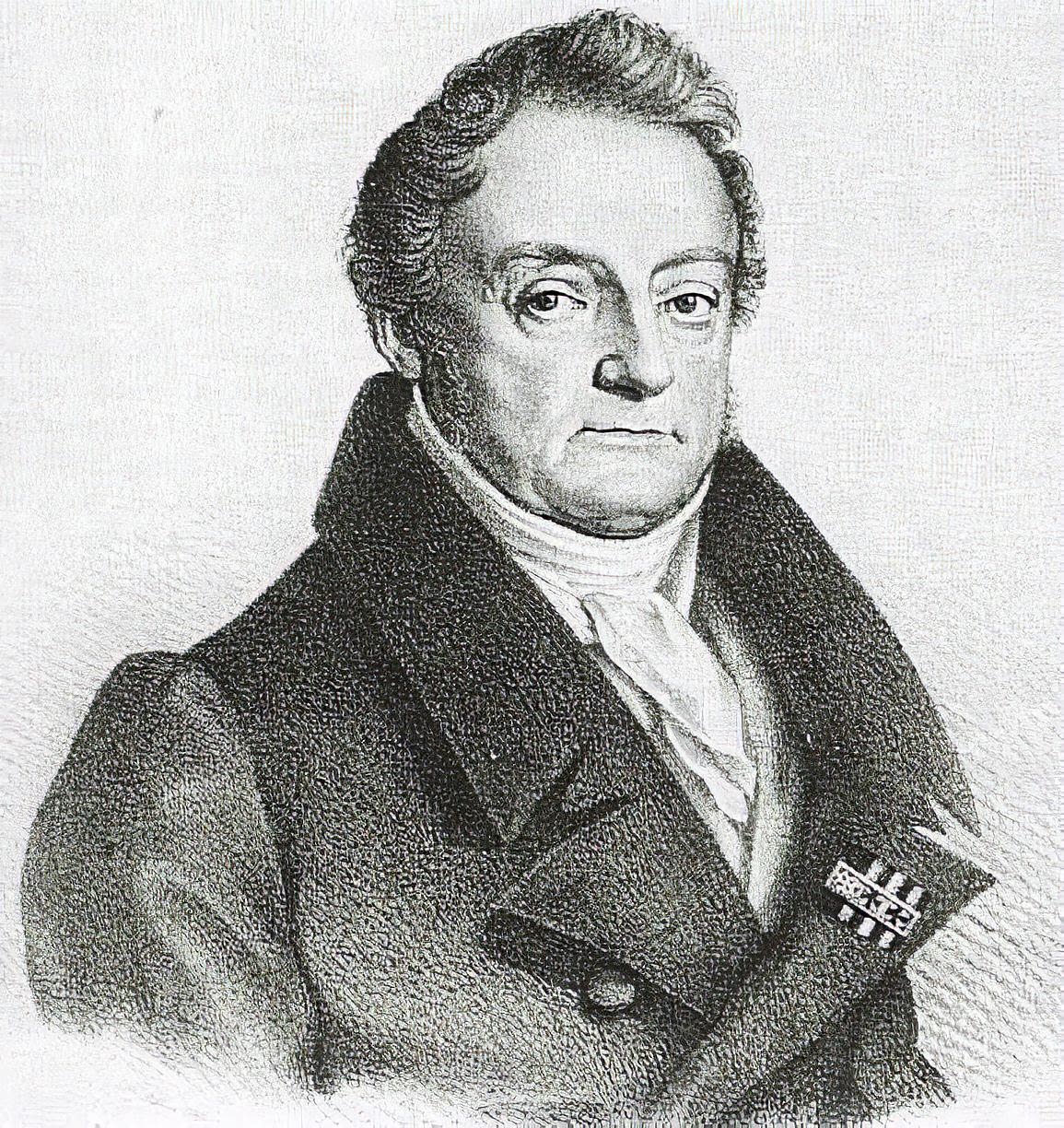

Baron Gottfried van Swieten, painted by C. Clavereau, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

As defined in the Oxford English Dictionary, a “patron” is “a person standing in a role of oversight, protection, or sponsorship to another,” and more specifically, “a person or organization that uses money or influence to advance the interests of a person, cause, art, etc.” Patrons hold a unique role: not only do they support someone, such as Beethoven, but they also have a role of guardianship, using their money and influence to oversee, protect, and advance the interests of who they choose to patron. In 18th- and 19th- century Bonn and Vienna, patrons ranged from supporters to mentors, influencing composers as they supplied them with money and encouraged them to take on certain works. Social historian William Weber notes that “in patronage we see reflected the social system which maintained the rhythm of contemporary taste.” Not only is the patronage system a means of encouraging the creation of art, but it is a system that reflects societal taste – patrons held great social power and dictated and reflected social trends. By investigating the role of three of Beethoven’s patrons – Waldstein, van Swieten, and Lichnowsky – we will illuminate the impact the patronage system had in developing Beethoven’s work and elevating his status.

Prince Karl Lichnowsky, painted by Leinwand von Goedel, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein, painted by Antonín Machek, retrieved from Wikipedia.

Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein, painted by Antonín Machek, retrieved from Wikipedia.

Baron Gottfried van Swieten, painted by C. Clavereau, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Baron Gottfried van Swieten, painted by C. Clavereau, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Prince Karl Lichnowsky, painted by Leinwand von Goedel, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Prince Karl Lichnowsky, painted by Leinwand von Goedel, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Count Ferdinand von Waldstein

Beginnings in Bonn

Count Ferdinand von Waldstein was the man who connected Beethoven from Bonn, his birthplace, to Vienna, where Beethoven unfolded his new phase of life. They grew acquainted through the von Breuning family, one of Beethoven’s family friends in Bonn. The young prodigy soon caught the attention of the Count who had a great interest in arts, which led Waldstein to become “Beethoven’s first and in every respect most important patron,” as Beethoven’s childhood-friend Franz Wegeler described.

Beethoven's House in Bonn, photographed by Thomas Depenbusch, retrieved from Flickr.

Short Trip to Vienna, 1787

In the late 1780s, upon receiving the knighthood of the Order, Waldstein served in the court of Elector of Bonn Max Franz. In 1787, perhaps under Waldstein’s intervention, the Elector offered Beethoven an opportunity to go to Vienna and see the great legend of the time – Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Although the trip was brief, it undoubtedly broadened the horizon of the 16-year-old composer. The ambience of the grand Austrian capital made Beethoven realize the narrowness of Bonn, which strengthened his decision to leave for the big city and involve himself in the aristocratic circle there. In other words, this short trip to Vienna in 1787 laid the foundation for the later long-term settlement in Vienna that would strengthen the composer’s reputation .

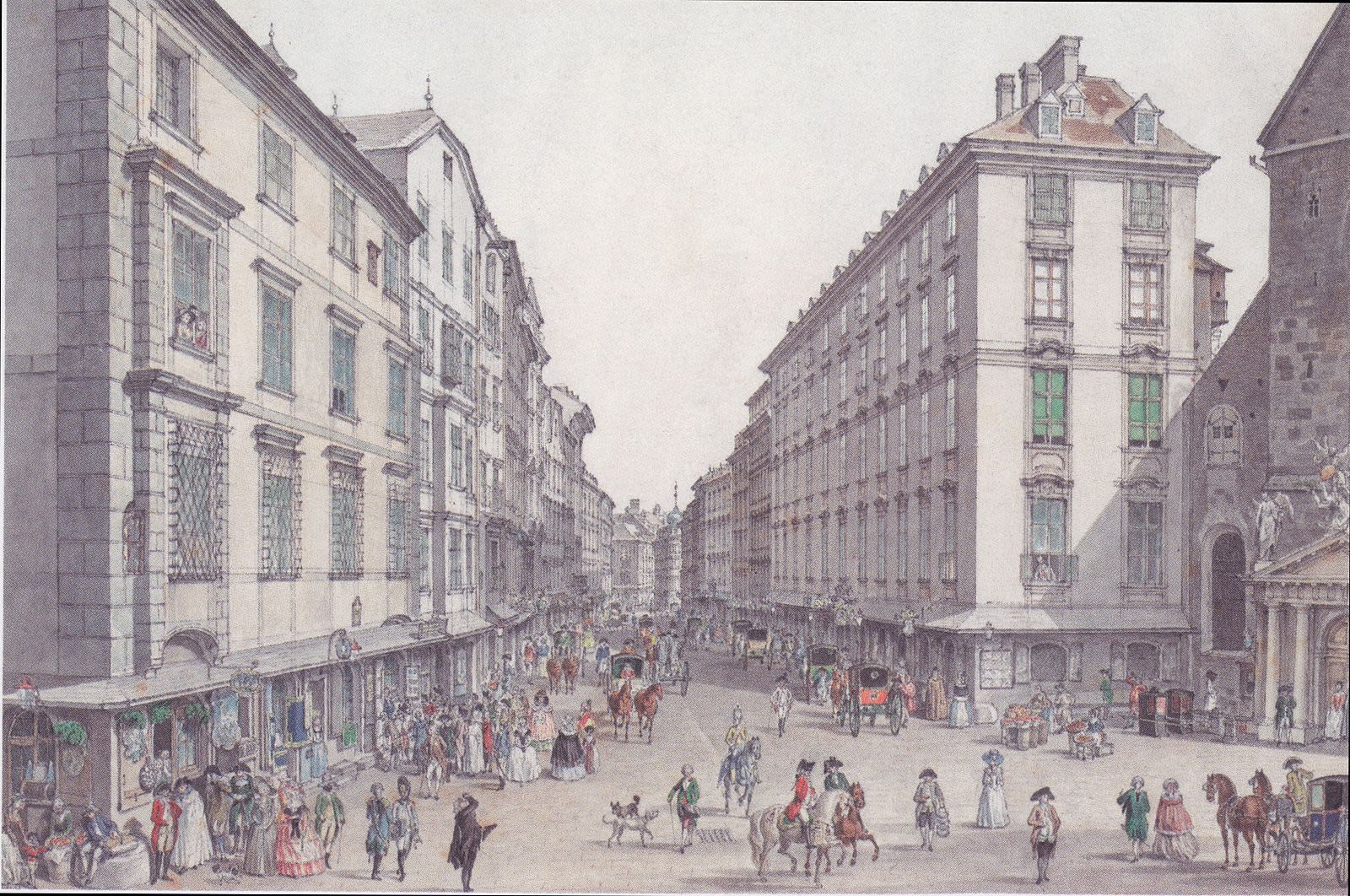

Der Kohlmarkt in Wien (1786), painted by Carl Schütz, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Influence on Beethoven's Composition

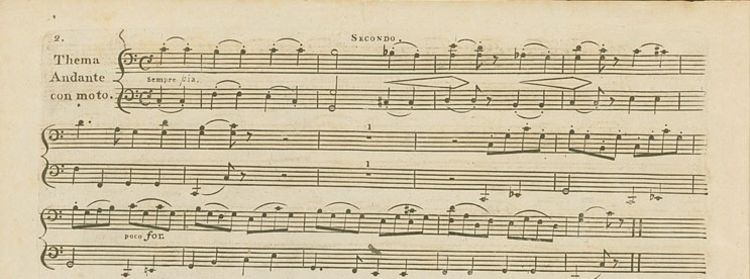

Besides financially supporting Beethoven, Waldstein – as a keyboard composer – also inspired Beethoven’s composition. His influence was found in the Eight Variations for Piano Four Hands on a Theme by Count Waldstein, WoO 67, which Beethoven composed around 1792. The main theme, composed by Waldstein, was a simple C-Major tune. Setting the tune as a departure point, Beethoven wrote a set of creative variations, from which we see the virtuosic piano-playing qualities and skills of formal innovation developed by the young composer. In this sense, what Waldstein offered to Beethoven was not only the economic support but also inspiration for his music.

Beethoven, WoO 67 - Main Theme (composed by Waldstein), from the First Edition, published by N. Simrock, retrieved from IMSLP.

Beethoven, WoO 67 - Main Theme (composed by Waldstein), from the First Edition, published by N. Simrock, retrieved from IMSLP.

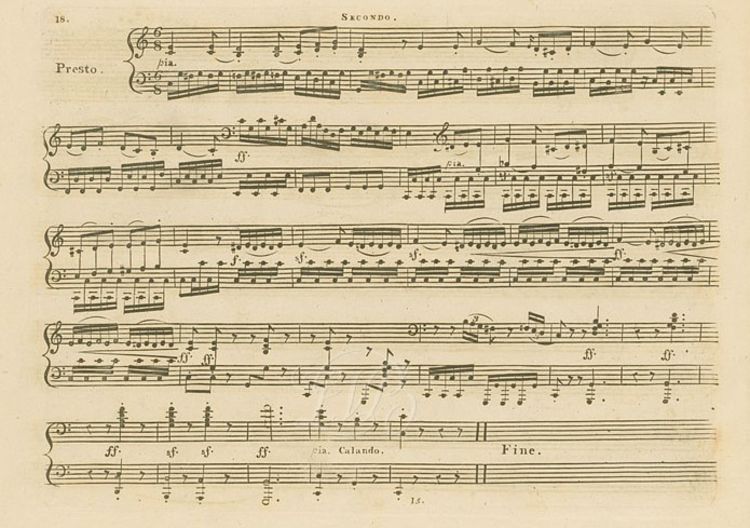

Beethoven, WoO 67 - Excerpt of Beethoven's Variations, from the First Edition, published by N. Simrock, retrieved from IMSLP.

Beethoven, WoO 67 - Excerpt of Beethoven's Variations, from the First Edition, published by N. Simrock, retrieved from IMSLP.

Beethoven's House in Bonn, photographed by Thomas Depenbusch, retrieved from Flickr.

Beethoven's House in Bonn, photographed by Thomas Depenbusch, retrieved from Flickr.

Der Kohlmarkt in Wien (1786), painted by Carl Schütz, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Der Kohlmarkt in Wien (1786), painted by Carl Schütz, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Move to Vienna, 1792

Waldstein’s patronage did not last very long because in November 1792, Beethoven decided to leave for Vienna permanently to pursue a broader career. On the eve of Beethoven’s departure, Waldstein wrote in an autograph album for Beethoven, saying,

“Dear Beethoven! You are going to Vienna in fulfillment of a wish that has long been frustrated. Mozart’s genius is still mourning and weeping the death of its pupil. (...) With the help of unceasing diligence you will receive the spirit of Mozart from the hands of Haydn. Your true friend, Waldstein.”

This inscription indeed gave Beethoven the confidence to explore the new musical world he had never seen before; and it well-predicted Beethoven’s future that he “[received] the spirit of Mozart from the hands of Haydn.” We can always spot Franz Joseph Haydn’s and Mozart’s shadow in Beethoven’s works, particularly those written in his first Vienna years since 1792. And through transforming the Classical tradition and developing his own style, Beethoven even transcended the legacy of his predecessors, which made him become the leader of a new musical age, as Waldstein prophesied.

However, Waldstein’s prophecy was also part of a larger narrative among the Viennese musical elite that Beethoven himself was the heir to the classical tradition, with Haydn as the father. Similar ideas to Waldstein’s “hands of Haydn” prophecy were published in various journals in Vienna during the 1790s, as well as in letters between various members of the aristocracy. All such accounts play up the relationship between Beethoven and Haydn, when in fact, they were perhaps not as close as described. Beethoven, upon refusing to inscribe “pupil of Haydn” at the top of his compositions, wrote to a friend that he did so because he had “never learned anything from [Haydn].” Despite this, the narrative about Beethoven as the heir to the classical tradition persisted. Thanks partially to Waldstein’s prophecy, Beethoven began his career in Vienna with the presumption of genius.

Vienna Cityscape, photographed by Julius Silver, retrieved from Pixabay.

Vienna Cityscape, photographed by Julius Silver, retrieved from Pixabay.

Dedication

Beethoven’s gratitude to Waldstein was still traced after their patronage relationship ended. His most well-known dedication to Waldstein was the Piano Sonata No. 21 in C Major, Op. 53, which he composed in 1804 – with more than a twelve-year span since their last meeting. When speaking of the dedication, the Beethovenian scholar Lewis Lockwood says, “the later dedication to Waldstein of the Piano Sonata Op. 53 probably reflects Beethoven’s gratitude for Waldstein’s early support rather than any obligation incurred at the time he composed the work in 1804.” Although Waldstein’s patronage only lasted till the early 1790s, his support to Beethoven had a profound influence on the composer, which changed the musical world even today.

Baron Gottfried van Swieten

Taking Root in Vienna

In Vienna, during Beethoven’s formative years in Bonn, Gottfried van Swieten was an Austrian diplomat and government official who was best known for his enthusiasm for music and for his patronage of great composers such as Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. He is largely known for being acknowledged as the leader of a group of the nobility which sponsored Haydn’s Creation and The Seasons; according to Anton Schindler, Beethoven’s first biographer, Beethoven was surrounded by “a group of oratorio devotees” in van Swieten’s circle.

Handel, Haydn, and Mozart

The most important years for the development of van Swieten's taste were those he spent in Berlin from 1770 to 1777. The standard of music in Berlin was not as high as it had been some years before, particularly since Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, one of its greatest assets, had left for Hamburg in 1768. Beethoven’s association with van Swieten at this time undoubtedly provided him with familiarity with Handel’s musical style as well. As written in David MacArdle’s Beethoven and Handel, "to van Swieten, surely, is due the credit of having founded in Vienna a taste for Handel’s oratorios and Bach’s organ and piano music there."

By the time of his return to Vienna, van Swieten's musical interests were not restricted to Bach and Handel, but it was these two composers who made the greatest impact on the musicians whom he patronized. A number of Mozart’s works of this period have the character of contrapuntal techniques, as one can find in the works of Bach. Haydn also received generous financial support for the Creation and The Seasons, much credited to van Swieten who was partly responsible for the character of Haydn's music in the two oratorios.

Background Pictures: Baron Gottfried van Swieten, painted by C. Clavereau, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Joseph Haydn Playing String Quartets, painted by Anonymous, retrieved from Wikipedia.

Influence on Beethoven

Although Beethoven never worked as closely with him as Haydn or Mozart did, he often visited van Swieten in his home for regular concerts and thought highly enough of van Swieten to dedicate his Symphony No. 1, Op. 21, to him. The Baron took Beethoven under his wing especially during his early years in Vienna and introduced him to the music of Handel and the poetry of William Shakespeare and Homer. He also hosted weekly gatherings in his home that focused largely on the instrumental and vocal music of Johann Sebastian Bach, C.P.E Bach, and Handel, which Beethoven participated in after his arrival in Vienna in 1792. Beyond these gatherings, van Swieten often invited Beethoven to his home and took an interest in Beethoven’s counterpoint studies with Haydn. However, it was van Swieten’s love for Handel that directly influenced Beethoven’s own compositions. For example, Beethoven composed twelve variations for cello and piano on a theme from Handel’s Judas Maccabeus. Similarly, the direct influence of Handel’s music can be found in stylistic similarities between Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and Handel’s Messiah, specifically in its choruses.

Prince Karl Lichnowsky

Poising Beethoven for Fame

Prince Karl Lichnowsky was probably Beethoven’s most ardent supporter in Vienna. Not only did the Prince provide Beethoven with a place to stay, but Lichnowsky provided Beethoven many of the connections that helped him establish himself as a renowned composer in Vienna. Lichnowsky himself was a passionate music lover, and as put by Lewis Lockwood in his biography of Beethoven, “he played chamber music by day and pursued women by night.” The Prince paid Beethoven an annuity of 600 florins and let him stay in an apartment in one of the Prince’s houses. While Beethoven certainly would have enjoyed the financial comfort that the Prince provided him, his time living in Lichnowsky’s house was certainly the closest that Beethoven ever was in his adult life to being a “servant-musician” like Haydn. Beethoven was known to have despised being in the servitude of a court like earlier musicians. Often he complained about the formality of dinners in the Prince’s house and preferred to eat alone in his apartment.

"a cynical degenerate and a shameless coward"

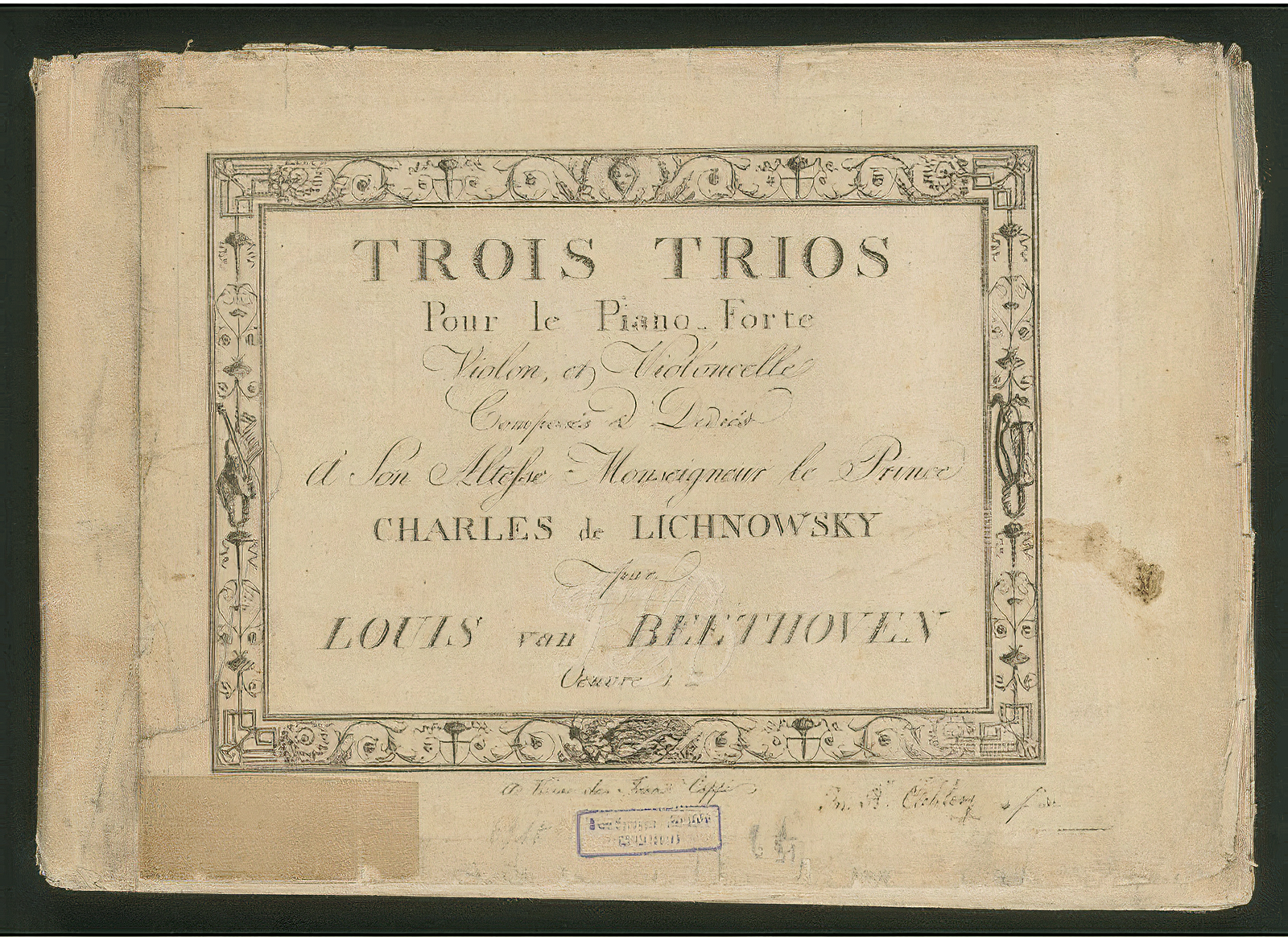

Financing the Piano Trios, Opus 1

Besides financially supporting Beethoven through his twenties, Lichnowsky’s support helped to expand Beethoven’s reputation. One example of Lichnowsky’s support was how he supported the publishing of Beethoven’s Piano Trios Opus 1. Composers in the late 18th century generally reserved opus numbers for published works they considered to be substantial, important compositions. While Beethoven had composed a significant number of large works before the Opus 1 piano trios, by labeling these pieces with an opus number, Beethoven signaled to publishers and the public alike that these pieces were the first of his “adult” works. Among the 249 first copies, the Lichnowsky family purchased about 50 (the Prince purchasing 20 for himself). The Prince possibly underwrote the fixed costs accrued by Artaria & Co., a prestigious publishing company at the time that had published first editions of many of both Haydn and Mozart’s works. By helping Opus 1 become a success, both in the eyes of the Artaria and the public, Lichnowsky helped to market Beethoven as a successful published composer which in turn aided Beethoven’s further publications. By 1801, Beethoven’s reputation among publishing companies had risen so much that he wrote to Wegeler: “for every composition I can count on six or seven publishers, and even more, if I want them.”

Beethoven, Piano Trios Opus 1 - Title Page, from the First Edition, published by Jean Cappi, retrieved from IMSLP.

Beethoven, Piano Trios Opus 1 - Title Page, from the First Edition, published by Jean Cappi, retrieved from IMSLP.

Travels Abroad

Lichnowsky also brought Beethoven with him on travels abroad to Prague, Berlin, Dresden, and Leipzig in 1796 as he had done with Mozart five years prior. For Lichnowsky, traveling with a musician such as Beethoven was a form of diplomacy that allowed cultural exchange with foreign ministers. For Beethoven such a trip meant that his reputation began to expand outside of Vienna. In Berlin, Beethoven met King Friedrich Wilheim II of Prussia, a patron of the arts who commissioned the Brandenburg Gate and an amateur cellist who loved music. Attracting the King’s favor, Beethoven dedicated his Sonatas for Piano and Cello Opus 5 to the King and premiered them while in Berlin.

Growing Reputation in Vienna

In his home in Vienna, Prince Lichnowsky cultivated a close, elite circle of music-lovers that gathered to listen to chamber music often played by hired professional musicians and often Beethoven himself. Among those hired by the Prince were Ignaz Schuppanzigh who was Vienna’s top violinist. Later, Schuppanzigh would help found one of the first professional string quartets, and he was instrumental in premiering Beethoven’s late string quartets. Beethoven was able to perform many of his early compositions like the Opus 1 piano trios at Prince Lichnowsky’s salons. However, Lichnowsky’s concerts presented Beethoven in a controlled setting, so that his audience could digest Beethoven’s style in a way that did not put them off to the young composer. These concerts exposed the 25-year-old Beethoven to the best musicians in Vienna and put him at the center of elite musical culture in Vienna with one of its most influential figures as his largest supporter. With the musical elite of Vienna behind him, Beethoven started his adult career with the reputation of a successful composer. As he continued through the rest of his career, his reputation would continue to grow, eventually becoming the giant of classical music he is today.

Background Picture: Brandenburg Gate, photographed by Dennis Jarvis, retrieved from Flickr.

"Ludwig van Beethoven – Ode to Joy" Installation in Bonn, photographed by Valdas Miskinis, retrieved from Pixabay.

"Ludwig van Beethoven – Ode to Joy" Installation in Bonn, photographed by Valdas Miskinis, retrieved from Pixabay.

Beethoven Statue in Vienna, photographed by Anonymous, retrieved from Needpix.

Beethoven Statue in Vienna, photographed by Anonymous, retrieved from Needpix.

Reframing Beethoven

"Ludwig van Beethoven – Ode to Joy" Installation in Bonn, photographed by Valdas Miskinis, retrieved from Pixabay.

As Beethoven journeyed from Bonn to Vienna, he journeyed from obscurity to fame through the support of three of his patrons: Waldstein, van Swieten, and Lichnowsky. As we can see, the creation of art is never the work of a single person – beyond requiring an understanding and awareness of the artists of the past, it demands support, often financial, to bring the art into existence. Beethoven is often described as a genius, and the label of genius often comes with the connotation of complete originality or even supernatural quality. Even Beethoven’s great originality had foundations in the work of other composers, such as Haydn and Mozart, and his patrons – through monetary support, guidance, and social status – provided him the framework for his art to take off from the ground.

"The creation of art is never the work of a single person."

Beethoven Statue in Vienna, photographed by Anonymous, retrieved from Needpix.

The system of patronage helped propel Beethoven to the status of genius he holds today; but, specifically in the year celebrating Beethoven’s 250th birthday, we can benefit from reframing and reexamining this status. Beethoven’s compositions were only made possible by the work of many people, and in this year where many of his works are being performed (more so than usual, at least before COVID-19 stole the spotlight), we can take the time to acknowledge and better understand those that made the creation of these compositions possible. Understanding the system in which art is created helps us gain a greater understanding of where the artist lies within it all, as well as bringing to light other elements that may go unseen. In a year of celebrating the work of Beethoven, exploring the patronage system is a step in reexamining Beethoven’s towering presence in the world of classical music and beyond.