Forever chemicals are everywhere. How worried should we be?

This is part of a special report on forever chemical contamination in Ohio. Ideastream Public Media reporters spent months investigating the impact of these chemicals to answer the question, "How worried should we be?" New radio stories will drop every Tuesday in January, 2024.

A recent study shows fish from Lake Erie are loaded with a class of industrial chemicals that have been leaching into the environment for decades.

PFAS or poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances, otherwise known as “forever chemicals,” are found in high levels in freshwater fish, including here in Ohio, according to a study published last year by the Environmental Working Group, an environmental advocacy group that researches PFAS. They also contaminate nearly half of the nation’s tap water, according to a study by the U.S. Geological Survey.

As a result of decades of environmental contamination, scientists say they’re also likely in the body of nearly every American.

'If there’s no advisories, what’s the concern?'

Click here to listen to the audio story on forever chemical contamination in Ohio's fish.

It was a busy autumn day at Cutright Fish Cleaning in Geneva, Ohio. The family-run business is the first stop for many charters returning from a day on Lake Erie, coolers bursting with fresh-caught fish.

Owner Dennis Niepokny said he’s not worried about chemical contamination in fish.

“I’ve been eating fish since I’ve been a young kid,” he said. “My dad used to bring home Lake Erie perch and other stuff, and it ain’t no problem.”

Lake Erie’s sports fishing industry generated $2.5 billion for the state’s economy in 2021, according to the American Sportfishing Association, and many who make a living off the lake are thrilled about rebounding populations of game fish, particularly walleye.

Whether that fish is contaminated with PFAS is not a top concern for some.

“The government can say everything they want to say about certain things, but we’re all going to die someday,” Niepokny added.

Fishing on the Rocky River in October 2023. [Ygal Kaufman / Ideastream Public Media]

Fishing on the Rocky River in October 2023. [Ygal Kaufman / Ideastream Public Media]

Meanwhile, his customers said they’ve never heard of PFAS.

“No, I’ve never heard of that,” said Charles Preer, a local fisherman. “I’ve been eating this fish for years and if it was something there, I should ought to be purple or mutated or something.”

Tony Huggins, also an area angler, had never heard of PFAS and raised a question of his own.

“If there’s no advisories, what’s the concern?” he asked, referring to the warnings state health departments issue about potential health hazards of consuming fish or game.

The Geneva marina provides access to some of the best walleye fishing on Lake Erie. Angler Tony Huggins of Akron inspects the catch. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

The Geneva marina provides access to some of the best walleye fishing on Lake Erie. Angler Tony Huggins of Akron inspects the catch. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

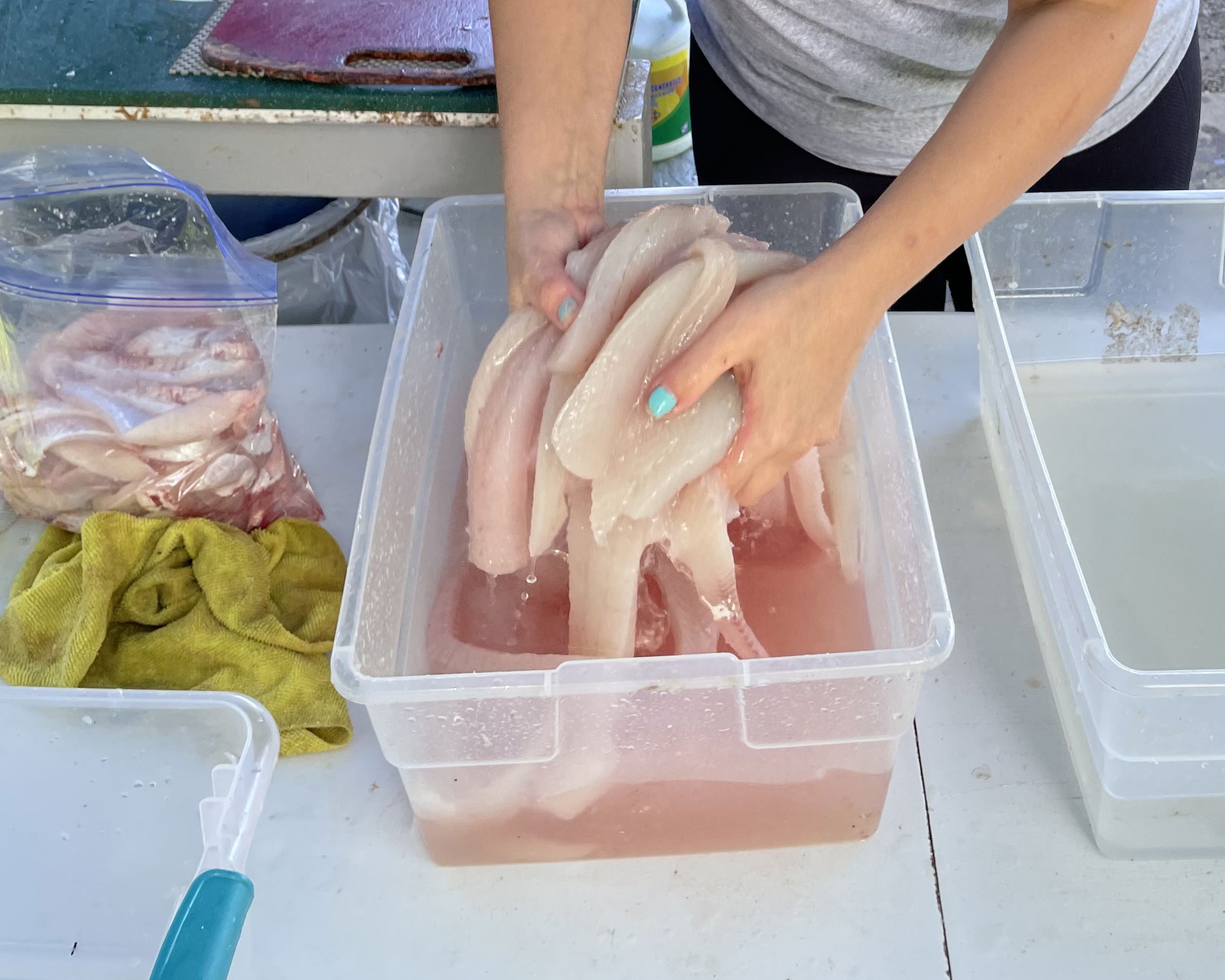

Devon Cutright slices bones off fresh caught walleye filets. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

Devon Cutright slices bones off fresh caught walleye filets. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

Family owned Cutright Fish Cleaning is busy throughout the season as anglers return with coolers full of walleye for processing. Lacie Cutright, left, Lisa Cutright, right. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

Family owned Cutright Fish Cleaning is busy throughout the season as anglers return with coolers full of walleye for processing. Lacie Cutright, left, Lisa Cutright, right. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

The problem with PFAS

PFAS are called “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down in the environment. Instead, they build up in living things, like Lake Erie perch, walleye and human beings.

David Andrews authored the study by the EWG that measured PFAS levels in fish across the nation. He said eating locally caught fish is often Northeast Ohioans’ highest source of PFAS exposure.

“Eating a single fish is equivalent to a year of drinking water at the recently proposed drinking water limit from the EPA,” Andrews explained.

In March, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed strict limits for six types of PFAS chemicals. For two of the most prevalent chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, the EPA proposed a limit of four parts per trillion.

[Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

[Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

Listen to the radio story on the health effects of forever chemicals here.

Studies show that PFAS are linked to increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of kidney or testicular cancer, decreases in infant birth weights, decreased vaccine response in children and increased risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia in pregnant women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In December, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, a World Health Organization Agency, classified one compound, PFOA, as carcinogenic to humans. PFOA is used to make fluoropolymer coatings and products that resist heat, oil, stains, grease and water, according to the CDC.

Philippe Grandjean, professor of environmental medicine at the University of Southern Denmark, is a pioneer in the study of PFAS’ health effects. He’s especially concerned with their impact on pregnant women and infants.

“The fetus and newly born child, those are the most vulnerable members of the population,” Grandjean said, adding that around half of the PFAS that accumulate in a mother’s body are passed on to the baby through breast milk. “So the child could get up to a ten-fold concentration in the blood.”

In March, a 20-year study found prenatal exposure to PFAS was associated with lower birth weight. Babies who don't weigh enough at birth are more likely to develop diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure as adults, according to the March of Dimes.

Toxicologist Linda Birnbaum, a former director at the National Institutes of Health, is one of the top experts on PFAS. What worries her most is how ubiquitous they are, she said.

“Every single one of us has these chemicals in our body. Some people have more than others and we don’t always know exactly why, but we all have it, and I think that’s concerning,” Birnbaum said. “I don’t know of a tissue or an organ system that hasn’t been shown to be impacted by PFAS.”

Grandjean said children exposed to PFAS have reduced immune function.

“We should be worried if we care about our kids,” Grandjean said.

Carla Ng, who studies PFAS at the University of Pittsburgh, echoed this concern for young people.

“It’s stuff that’s been in us since before we were born and that we know are linked to some important health effects, and we do see, at the population level, worrying changes in human health. We see declines in fertility. We see greater incidences of chronic disease at younger ages,” Ng said.

Environmental impact

Ohio is part of the Great Lakes Consortium that, in 2019, set guidelines on eating PFAS-tainted fish. But Ohio, unlike surrounding states, has not yet issued warnings about the contamination.

Michigan has had warnings about PFAS for more than a decade.

“Our goal is really to keep people informed, make sure people have the information that they need to make those decisions and balance the risk and the benefits for themselves and their families,” said Brandon Reid, manager of Michigan’s Eat Safe Fish Program.

Michigan even conducts its own PFAS testing of fish caught in contaminated waters, Reid said.

“We actually do the testing of the fish through MDHHS [Michigan Department of Health and Human Services], he said. “We do coordinate with the environmental department to get those samples of fish to test as well as to prepare those fish for testing and then to kind of compile all of that data,” Reid noted.

Michigan’s warning says do not eat any fish with over 300 parts per billion PFAS. Parts per billion is a unit of concentration.

The Great Lakes Consortium puts that number at 200 parts per billion. Under that, the recommendations vary for how often you should eat the fish that have lower concentrations.

Two people fish on a dock at Rocky River. [Ygal Kaufman / Ideastream Public Media]

Two people fish on a dock at Rocky River. [Ygal Kaufman / Ideastream Public Media]

Ohio will begin monitoring water and wildlife samples for PFAS in 29 of the state's rivers, Gov. Mike DeWine announced in December 2023. That testing should be completed in the fall of 2024. [Ygal Kaufman / Ideastream Public Media]

Ohio will begin monitoring water and wildlife samples for PFAS in 29 of the state's rivers, Gov. Mike DeWine announced in December 2023. That testing should be completed in the fall of 2024. [Ygal Kaufman / Ideastream Public Media]

A Lake Erie walleye caught near Geneva had more than 50 ppb PFAS, according to a 2023 study by the EWG. Under the consortium's recommendations, a walleye like that is only safe to eat once a month.

But some people say even that threshold is too high. Tony Spaniola is one of them – he’s the co-chair of the Great Lakes PFAS Action Network, a coalition dedicated to preventing PFAS contamination and cleaning it up.

“In fact, the Michigan ‘do not eat’ level is probably 30 to 100 times too high,” Spaniola said. “If the more appropriate level were applied, there wouldn't be a whole lot of fish in the Great Lakes that are safe to eat, so obviously that applies to Lake Erie, too.”

Ohio is behind the curve compared to other Great Lakes states, he said.

“The fact that there aren't guidance levels issued for Ohio is something that, if I lived in Ohio, I would be concerned about,” he said.

The Great Lakes Consortium recommends eating no more than one walleye per month that contain more than 50 ppb PFAS. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

The Great Lakes Consortium recommends eating no more than one walleye per month that contain more than 50 ppb PFAS. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

The Ohio Department of Health, which issues fish consumption advisories, said in a statement that current recommendations consider risks posed by mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls, called PCBs, but not PFAS, which are still “being discussed.”

The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency will begin testing water and fish in 29 Ohio rivers for PFAS contamination, Gov. Mike DeWine announced in December. Those findings will “give insight on the potential for any sport fishing consumption advisories,” according to a media release.

What do PFAS do in our bodies?

PFAS don’t exist in nature, but they mimic chemicals the body needs, like nutritious fatty acids and the lipids that make up our cell walls.

That’s where the trouble starts, according to Ng, of the the University of Pittsburgh.

The nonstick properties of perfluoroalkyls that make skillets slippery and sofas stain-resistant comes from the F in PFAS: fluorine.

“Part of the problem with PFAS is that they look like a fatty acid and so they’re able to have interactions with fatty acid receptor, but that carbon-fluorine bond is so strong that they can’t be processed so they go in there and your body goes, ‘Oh hey, we got more fatty acids, let’s go and process them,’ and they can’t,” Ng explained.

How worried should we be? Ng said the answer lies at the molecular level.

“Because fatty acid metabolism is so important to so many different processes in the body, it makes sense to me that PFAS would have such a cascade of toxic effects related to so many different systems,” Ng said.

In a report issued in 2022, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found an association between PFAS and decreased immune function, abnormally high cholesterol, low birth weight and increased risk of kidney cancer.

It groups people into three risk levels: low, medium and high, based on the amount of PFAS in their blood.

“Most people in the U.S. are in that middle group,” said Dr. Ned Calonge, who chaired the committee.

Despite the fact that most people fall into that group, experts said having your blood tested for PFAS is not easy and can be expensive. Calonge added most medical providers aren’t sure what to do with the results anyway.

“We’ve never had a good connection between environmental health exposures and primary care and medical practice,” he said.

The report recommended testing cholesterol levels in everyone ages 9 and up, screening for lower birthweight and preeclampsia during prenatal visits, routine thyroid function tests for newborns and mammograms to check for breast cancer in women over 40.

“I don’t know what the right answer is, and I don’t think anyone knows what the right answer is,” added report contributor Dr. Alex Kemper at Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus.

Ultimately, it's up to individuals to determine how worried they are about PFAS and then pressure the medical community to catch up, he said.

A Cincinnati lawyer has spent decades fighting chemical manufacturers. Here's where public awareness of PFAS began

Robert Bilott won the world’s first-class action lawsuit against a PFAS manufacturer. His story was made into a movie, “Dark Waters” starring Mark Ruffalo. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

Robert Bilott won the world’s first-class action lawsuit against a PFAS manufacturer. His story was made into a movie, “Dark Waters” starring Mark Ruffalo. [Jeff St. Clair / Ideastream Public Media]

Are there forever chemicals in your home? Here's what our tests showed

There’s growing awareness of industrial chemicals that have spread throughout our water systems, food sources and into our bodies.

They’re called PFAS or ‘forever chemicals’ – known for their nonstick and waterproof properties. The nonstick properties of perfluoroalkyls that make skillets slippery and sofas stain-resistant come from the F in PFAS: fluorine.

How worried should we be?

We wanted to find out just how common PFAS are in our home environments, so we created our own Forever Chemicals Test Kitchen.

Many common consumer goods are said to contain PFAS. We wanted to see for ourselves so we tested nonstick skillets, waterproofing sprays, makeup and fast food wrappers.

Scroll down to check out the results of our tests in the videos below featuring Ideastream reporters Taylor Wizner and Zaria Johnson.

PFAS in your home?

Although they’ve been linked to a number of illnesses, PFAS are still commonly used in many consumer products.

They’re so widespread, the CDC says nearly every person in America has some PFAS in their blood.

Here's what we found when we tested two common waterproofing sprays.

Results begin at :53.

How did they get in our bodies?

If you’ve eaten locally caught fish in the past 30 years that’s one way, or used waterproofing sprays, drank contaminated drinking water, purchased stain-resistant furniture, used certain brands of dental floss or used waterproof makeup you may have come in contact with this class of chemicals.

Here's what we found when we tested common makeup brands.

Results begin at :53.

The Environmental Working Group publishes a database of cosmetics consumers can search to determine if a product may contain PFAS.

Ideastream host Jeff St. Clair was an analytical chemist before getting into radio. He devised a method to extract samples from our items using hot water and a little vinegar.

The sample is called a ‘leachate’ because it simulates the leaching process of heat and moisture in everyday situations.

Here's what we found when we tested nonstick skillets, one of the products most widely known to contain PFAS.

Results begin at :53.

We also tested fast food wrappers from local drive-thru restaurants. PFAS are used in wrappers to prevent food and grease from leaking through the packaging, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Here's what we found.

Results begin at :53.