The Six (or more) Degrees of Separation

Beethoven Edition

“The celebration of a centenary is always a great occasion for idolatry. […] Beethoven has become a religion. The nineteenth century witnessed a widespread collapse of orthodoxy in Christian doctrine and at the same time a profound deepening of the fundamental religious instinct. Many people who could no longer submit whole-heartedly to the authority of a church turned towards music as a substitute for theology.”

Those words were written by English musicologist Edward Joseph Dent, writing in 1927, a hundred years after the death of Beethoven. In the years following his death, the life and music of Beethoven was revered, scrutinized, and in some ways beatified. Writers, and especially composers, find themselves increasingly separated from the reality of the historical Beethoven. They only have his music and their visceral, “religious instinct” toward it. This contributed to a not insignificant amount of historical revisionism that still clouds our perception of him and the performance of his music today. Was he simply a man of his time who wrote music, or was he something else or something more?

To better suit the spirit of their time, it was not uncommon for conductors, particularly Wagner and Mahler, to edit and re-score Beethoven's symphonies for performance. Whether this means adding instruments, removing instruments, changing dynamics, or making wholesale cuts to the music itself, most would see this is as an unconscionable act today. However the experience has been recreated, on occasion, in the spirit of historical curiosity. The spirit of our time favors authenticity and the "composer's intent," but while we may not be able to reach the heart of the “real” Beethoven, whatever that means to you, we are probably getting closer.

While some view Beethoven with reverence others question his relevance. Much virtual ink will be spilled on the subject as we observe the 250th anniversary of the composer’s birth. There is room for both opinions in our discussion, whether we like it or not, and these arguments are what have fueled two centuries of scholarship and debate on the composer.

Beethoven, a Man of His Time

Ludwig van Beethoven broke new musical ground, particularly in the areas of instrumental music. During his early, formative years in Vienna, he studied composition with Joseph Haydn. Haydn is often called the “father of the symphony” and the “father of the string quartet.” It is in precisely these two genres where we find Beethoven’s deepest influence.

In the Classical period (1750-1820), concert-goers didn’t pack the halls to hear the latest symphony. Audiences wanted to hear arias from their favorite operas performed by the hottest stars of the day. Vocal virtuosity sold tickets. The symphony, often performed as separate movements, acted as a sort of musical sorbet between courses of vocal numbers. Coinciding with the proliferation of high-quality, professional orchestras, we start to see not only the symphony performed as a single composition, but also as a vehicle for the highest of musical and human ideals. This approach anticipates the symphonies of Johannes Brahms and later, Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner.

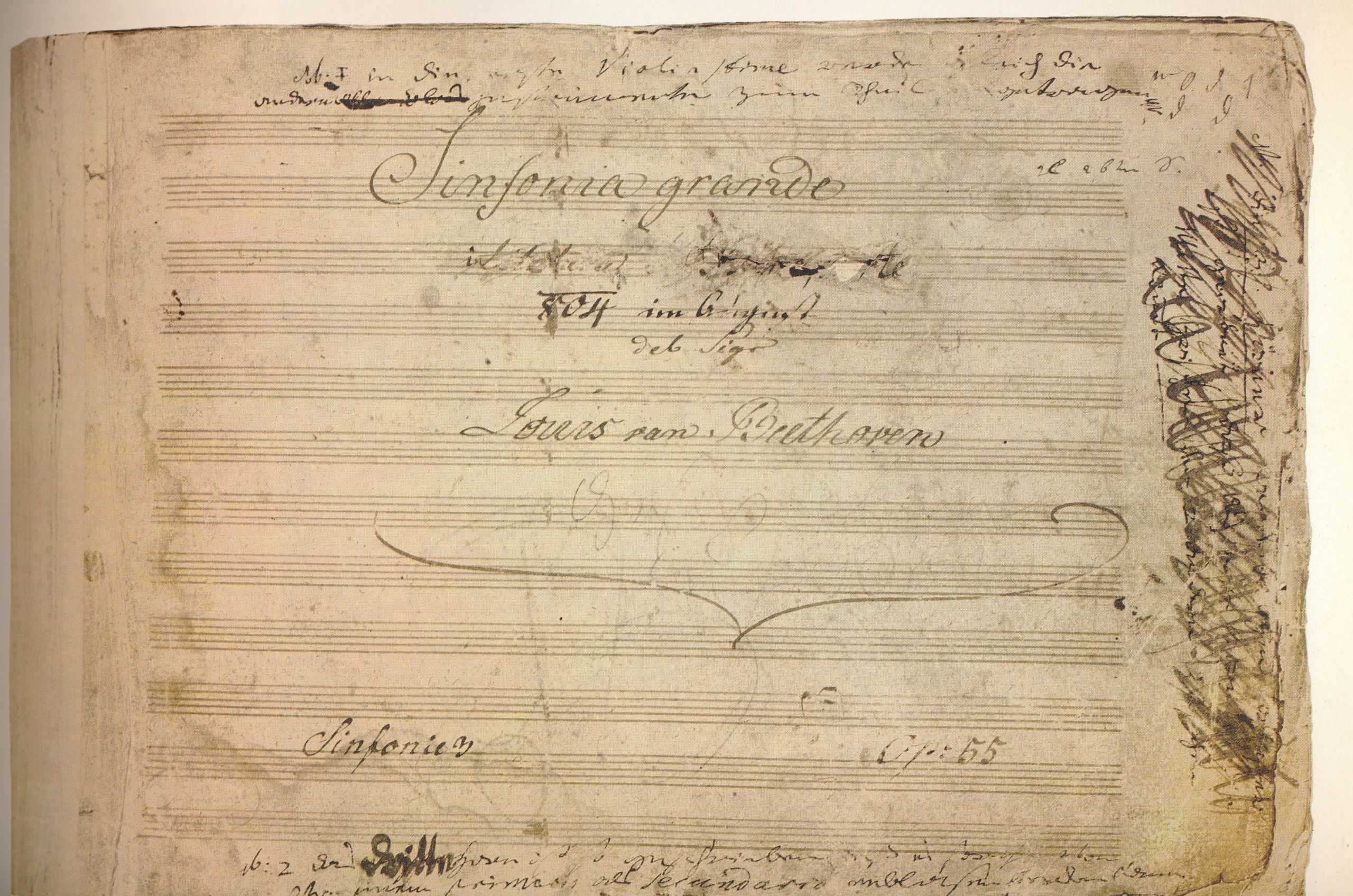

Beethoven, through his symphonies, expanded the symphonic form to include societal ideals as well. We see an excellent example of this in his third symphony, Eroica (“Heroic”). He originally dedicated the work to Napoleon Bonaparte because Bonaparte embodied the ideals of the French Revolution of democracy and anti-monarchy. However, when Napoleon declared himself emperor in May of 1804, Beethoven flew into a fit of rage and exclaimed, “So he is no more than a common mortal! Now, too, he will tread under foot all the rights of Man, indulge only his ambition; now he will think himself superior to all men, become a tyrant!” Beethoven tore the title page of the score in half, scratched out the dedication to Napoleon, and the work was eventually published as “Heroic Symphony, Composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.”

Title page to the manuscript of Eroica with the dedication to Napoleon scratched out.

Title page to the manuscript of Eroica with the dedication to Napoleon scratched out.

The string quartet as a genre exists today thanks to the efforts of Joseph Haydn. The combination of two violins, viola, and cello existed long before him, but treating them as equal voices and capable of “high art” music can be traced to him.

In the hands of Beethoven, Haydn’s pupil, the genre developed in an experimental direction with all tradition of form thrown out the window by the end. Particularly in the late quartets, he pushed the limits of harmonic and personal expression.

Not only did Beethoven break tradition and new ground with his symphonies and quartets, his music gave license to others to question musical dogma. Who says you can’t add voices to a symphony? Why can’t we plumb the depths of human expression outside of opera? Beethoven can be viewed as a “composer of music” and a “composer of ideas” and it’s through this lens that we look at Beethoven’s legacy.

"Composer of Music"

Toward the end of Beethoven’s career, early Romantic composers such as Carl Maria von Weber began incorporating supernatural elements into operas while larger, structured forms popular in the Classical period were being abandoned in favor of smaller lyric pieces. As a response, Beethoven began a study of Bach and Handel. To move forward, he looked backward. These Baroque masters inspired him to revisit the older forms and styles and create a synthesis of form, structure, innovation, and personal expression. Instead of the popular small orchestral miniatures, Beethoven doubled-down on the symphony.

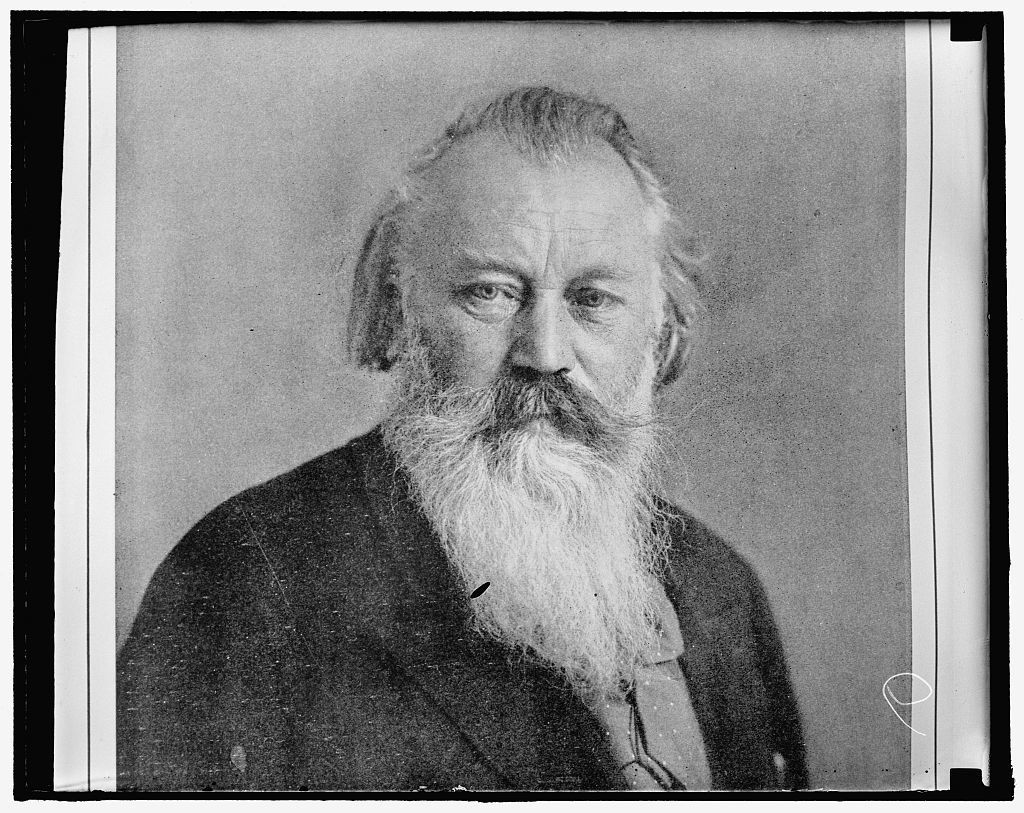

This blending of old and new is a thread that was picked up by musical conservatives such as Johannes Brahms, Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, and Robert and Clara Schumann. Although they could never have met, Johannes Brahms was often considered the musical torchbearer of Beethoven. Like Beethoven, Brahms rejected the trend of program music, which was embraced by the “New German” school of composers. Musicologist Karl Geiringer writes that, “Brahms was sincerely attached to the past and felt himself the guardian of great traditions.” Although musically at odds with the Wagnerians, Wagner himself thought well of Brahms as a composer saying, “One sees what may still be done in the old forms with when one comes along who knows how to use them.”

Johannes Brahms | Library of Congress

Johannes Brahms | Library of Congress

The musical conservatism of Mendelssohn and Brahms found a home in the Brits, Charles Villiers Stanford and Hubert Parry. Parry and Stanford taught an entire generation of English composers at the Royal College of Music in London. Among their students were Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams.

"Composer of Ideas"

After Beethoven’s death, while some composers attached themselves to “Beethoven the composer of Music,” others found their musical home in “Beethoven the composer of Ideas.”

“In terms of reception, Beethoven’s late music represents a complex case. Well into the second half of the nineteenth century, much of it, beginning with the Ninth Symphony, was dismissed in many academic and amateur circles, even in Vienna, as obscure and possible influenced, not for the better, by Beethoven’s isolation and deafness. By the end of the century, the late music became the object of intense admiration.”

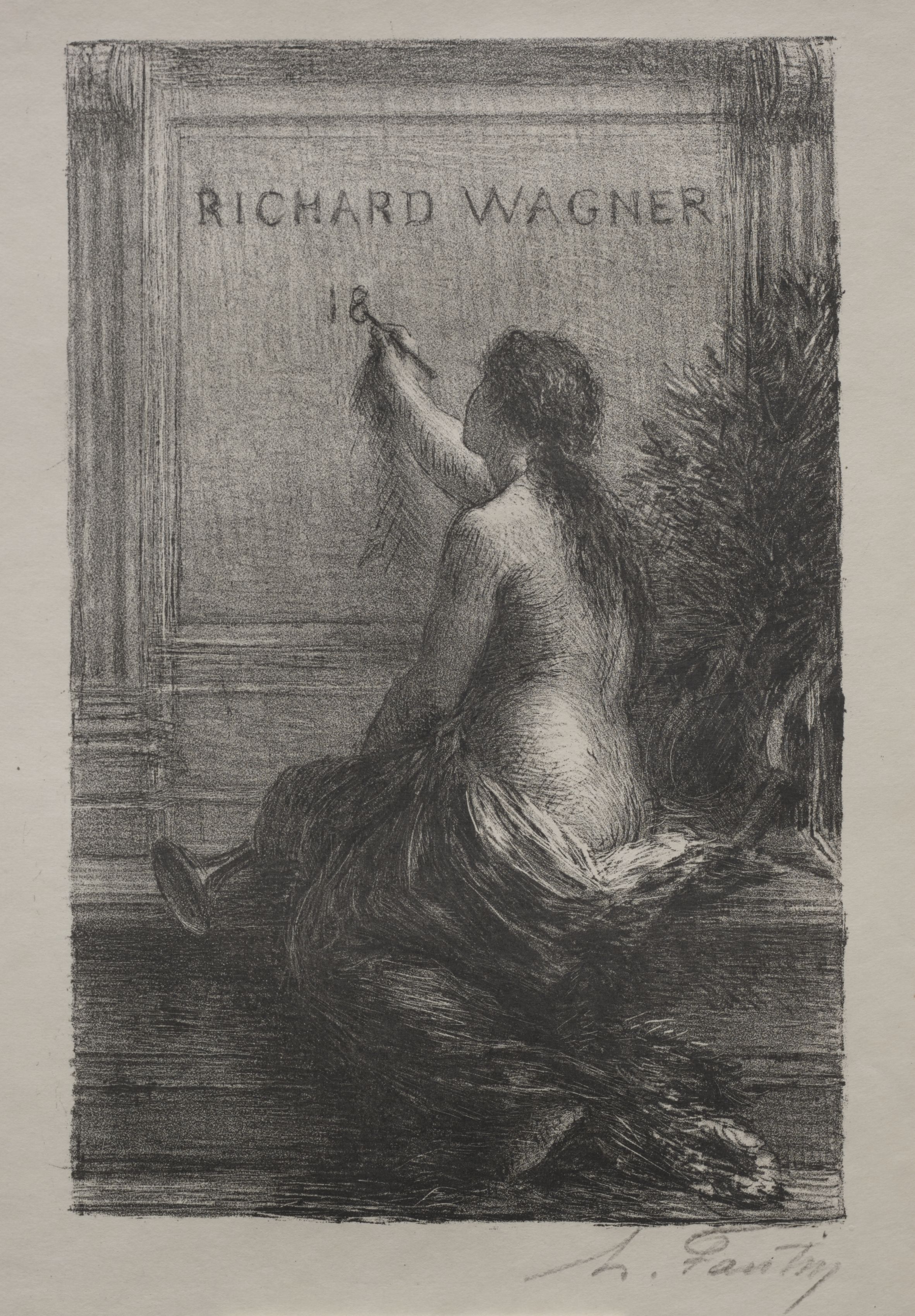

It’s Beethoven as an innovator of form and harmony where the likes of Richard Wagner find their home.

Richard Wagner. Photograph by Franz Hanfstaengl, 1871.

Richard Wagner. Photograph by Franz Hanfstaengl, 1871.

As Beethoven’s deafness became more pronounced, his use of harmony became less rooted in tradition. (Whether this is a case of one following the other or a coincidence of maturity remains a very hot topic of debate.) The late quartets of Beethoven, opp. 130-132, illustrate this with daring harmonies, emotional depth, and between five and seven movements each instead of the traditional four.

Beethoven’s expansion of the symphonic form and license to experiment laid the path for further innovation from Wagner and company. Wagner pushed the limits of traditional tonality and made liberal use of dissonance to illustrate a wide spectrum of emotion, which laid the path for the total abandonment of traditional harmony by the beginning of the 20th century.

Wagner used the German word Gesamtkunstwerk - literally “total artwork” - to describe his approach to opera. To Wagner, this meant a unification of all forms of art in the theater. Music, literature, and visual art were all harnessed to serve the same artistic end. Although he never used the term, his musical technique of leitmotif (“leading motive”) – a short musical phrase associated with a place or person – is ubiquitous in film music today.

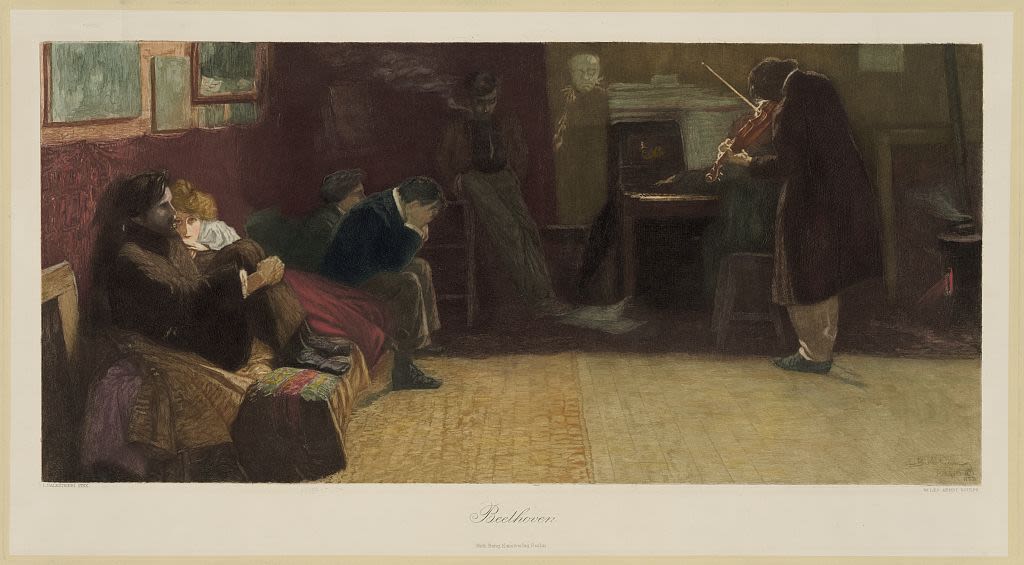

Henri Fantin-Latour, "Immortality" (1886) | Cleveland Museum of Art

Henri Fantin-Latour, "Immortality" (1886) | Cleveland Museum of Art

Among the “Wagnerians” were Franz Liszt and Hector Berlioz. Liszt was a student of Carl Czerny, one of the only formal students of Beethoven. Franz Liszt popularized the programmatic symphonic poem while applying Romantic ideals and his own brand virtuosity to his work. Berlioz wrote tremendously grand music inspired by the visual arts, theater, legend, and at least once, opium. Richard Strauss remarked the Berlioz was the “inventor of the modern orchestra.” The three composers – Wagner, Liszt, and Berlioz – made up what Franz Brendel called the “New German School.” Although Liszt and Berlioz were not German (Hungarian and French, respectively), their musical traditions and idioms were grounded in Germanic music.

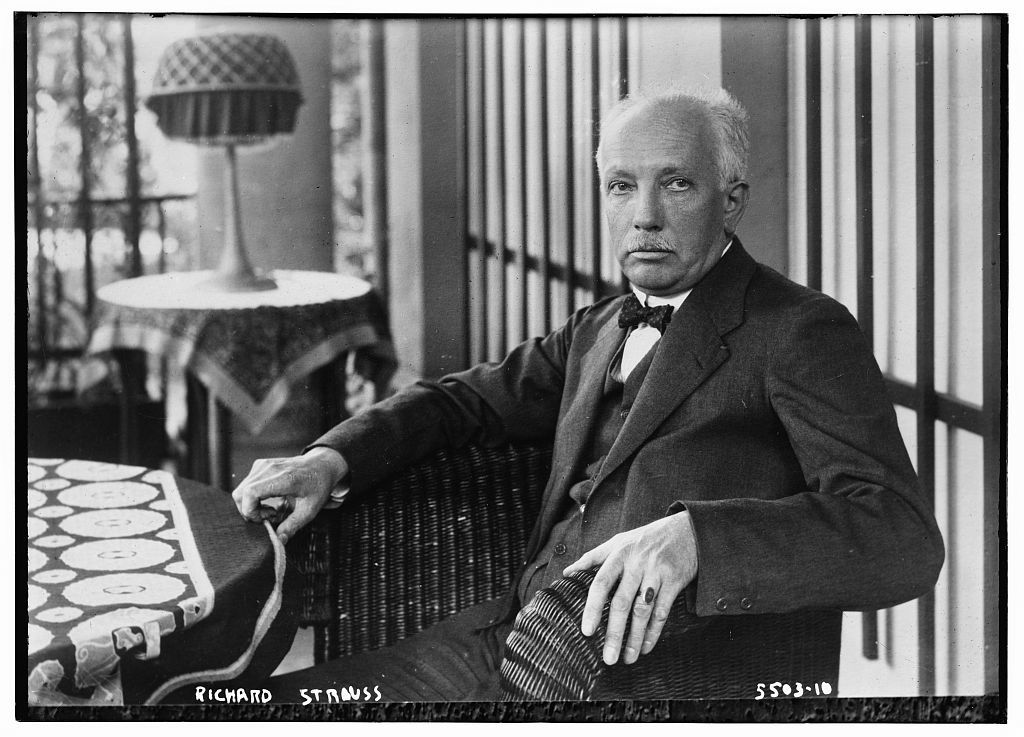

When Richard Strauss first heard music of Wagner, he viewed it with deep suspicion and hostility – a stance he later regretted. The music of Wagner and his associates are responsible for the flourish of German late-Romanticism. Strauss later came to admire not only the music of Wagner, but also the musical ideals of Wagner and Liszt. Strauss, along with his friend Gustav Mahler, was instrumental in continuing harmonic innovation and the expansion of symphonic forms – Mahler with his symphonies and Strauss with his tone poems and operas. All of this can trace its roots back to Beethoven.

Richard Strauss, Bain News Service | Library of Congress

Richard Strauss, Bain News Service | Library of Congress

In his early compositions, Arnold Schoenberg stretched the limits of traditional harmony, incorporating elements of both Wagner and Brahms. Many of Schoenberg’s early compositions fit squarely in the mold of German late-Romanticism. Later, he pioneered twelve-tone serialism and atonal composition, though he personally hated the term. These compositional techniques are the logical extension of the harmonic innovations that came before. Schoenberg is considered the father of the Second Viennese School, a musical movement succinctly described by his phrase “the emancipation of dissonance.” Schoenberg’s most prominent students were Alban Berg and Anton Webern. After moving to the United States to escape WWII, he also taught Americans John Cage and Lou Harrison.

Beethoven in France

It is at this point that we turn our focus away from Germanic parts of Europe and look to France. In the century or so following Beethoven’s death, the center of musical training in France was at the Paris Conservatory. Beginning in 1822, Luigi Cherubini led the Conservatory. Cherubini’s great success lay in his operas, the most popular musical form in France next to ballet. In 1805, he traveled to Vienna to mount a production of one of his operas. And although the longtime resident of Paris found his time in Vienna unpleasant, he met the younger Beethoven and made a great impression on him. Cherubini did not like Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, and described the man as “an unlicked bear cub.” Despite their short time together and apparently spared pleasantries, Beethoven described Cherubini as the greatest of his contemporaries.

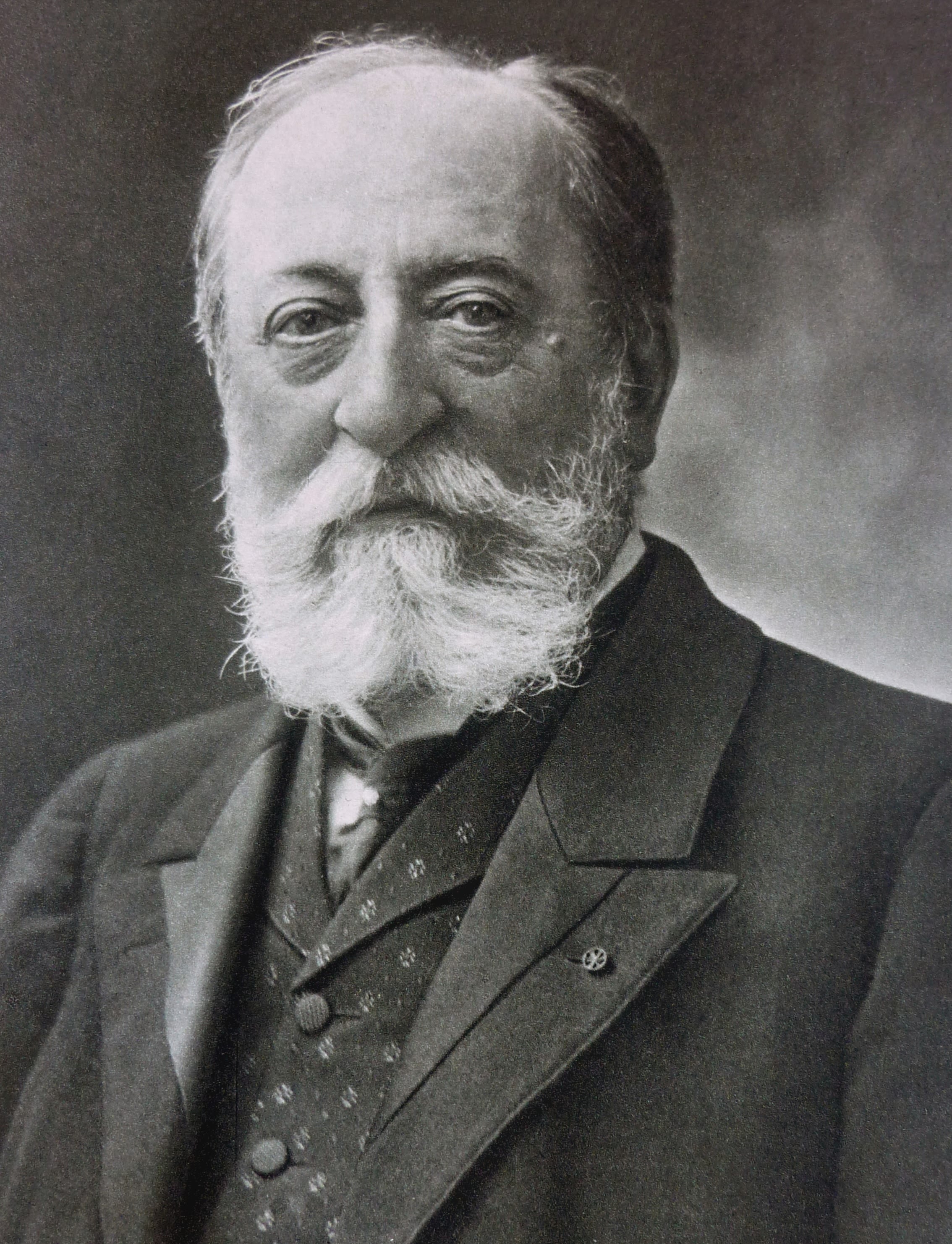

When Cherubini died, Daniel Auber took the helm of the conservatory and although the musical program was relaxed a bit, the musical curriculum remained conservative. This famously did not sit well for a number of students, among them Camille Saint-Saëns.

Camille Saint-Saëns, Photograph by Nadar.

Camille Saint-Saëns, Photograph by Nadar.

The great influence of Saint-Saëns is not so much in his compositions (which were considered rather conservative), but in his teaching and his advocacy of Germanic music in Paris. Saint-Saëns was an admirer of the symphonic poem made famous by Franz Liszt and brought the music and musical ideals of Schumann, Liszt, and Wagner to wider audiences and students in France. Saint-Saëns briefly held one teaching post in his career, but counted among his students Gabriel Fauré, who would later become a dear friend and a national hero for his own musical contributions.

By the end of his career, Saint-Saëns was seen as a reactionary and old-fashioned in the face of the radical Second Viennese School and the work of Igor Stravinsky and other modernists making waves in France. However, it is through his student, Gabriel Fauré, and Fauré’s student, Nadia Boulanger, that we see an extension of Beethoven’s influence into the United States.

Nadia Boulanger and Music of the United States

The daughter of a French composer and a Russian princess, Nadia Boulanger had a profound impact on music in the 20th century and beyond.

At age nine, Nadia Boulanger entered the Paris Conservatory to study with, among others, Gabriel Fauré. She left the Conservatory in 1907, set up a teaching studio in her home, and taught there and elsewhere until her death in 1979. In her lessons, she made sure that students had a wide understanding of music. They were required to study the masters and release any dogmatic adherence to one style or another. Alongside piano sonatas and string quartets of Beethoven, church cantatas by Bach, and early polyphonic works, Boulanger also showed the musical present with works by her friend, Igor Stravinsky, and contemporaries Debussy and Maurice Ravel.

“A good waltz has just as much value to her as a good fugue, and this is because she judges a work solely on its aesthetic content. […] Some people think that because you like Stravinsky you cannot also like Beethoven, or that an admiration of Johann Strauss is incompatible with a love of Bach. To Nadia Boulanger such an attitude would be incomprehensible.”

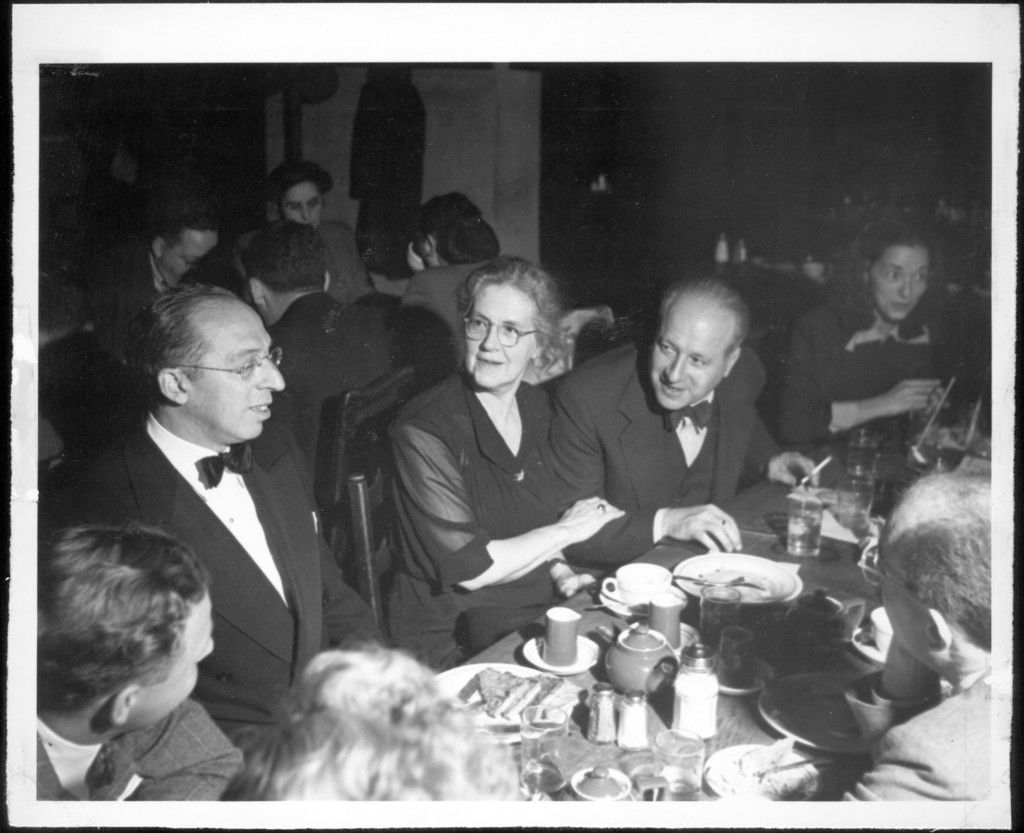

Aaron Copland, Nadia Boulanger, Walter Piston at the Old France restaurant, Boston, 1945 | Library of Congress

Aaron Copland, Nadia Boulanger, Walter Piston at the Old France restaurant, Boston, 1945 | Library of Congress

A lot of musical life in the United States during the first two-thirds of the 20th century was concentrated on the East coast at prestigious universities, and there you’ll find Boulanger’s students: Elliot Carter taught at Cornell and Julliard and Walter Piston taught at Harvard. Boulanger also taught Aaron Copland, Phillip Glass, Adolphus Hailstork, Gian-Carlo Menotti, and Virgil Thomson. If you back up a few musical generations, you can also trace Beethoven’s influence through Mendelssohn and Liszt, through Carl Reinecke and Josef Rheinberger, to Yale’s Horatio Parker and Princeton’s Roger Sessions.

Although Beethoven’s musical influence fades over time, every western musician owes at least a small part of who they are today to him. Through the development of the symphonic forms to the depths of expression found in the smallest keyboard works, echoes of Beethoven are still heard. The musicians for whom today’s composers write grew up learning Beethoven’s sonatas, concertos, and symphonies. For the average listener, the platonic ideal of a symphony is probably found in Beethoven.

But as we all acknowledge the past in this milestone year, it’s important not to dwell in it. Beethoven’s musical legacy should be a flame that lights our way, not one to hold vigil to the past.

Photograph of Bust of Beethoven by Hugo Hagen | Library of Congress