A Place Called Home

Cleveland's Woodhill Homes tells the story of public housing. It began in the 1930s with promise and enthusiasm but since has suffered funding shortfalls and stigma. But there are plans for a brighter future.

Woodhill Homes in Cleveland is one of the earliest public housing developments in the nation, opening its doors in 1940.

Woodhill's story reflects that of urban public housing across the United States: It opened to great fanfare, then functioned as housing for working-class families for several generations. But policy changes led to insufficient federal funding and eventually disrepair, even as families continued to call it home.

Now, Woodhill may be getting an update. A new plan funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development is imagining how Woodhill Homes and the surrounding neighborhood could be renovated or rebuilt for the future.

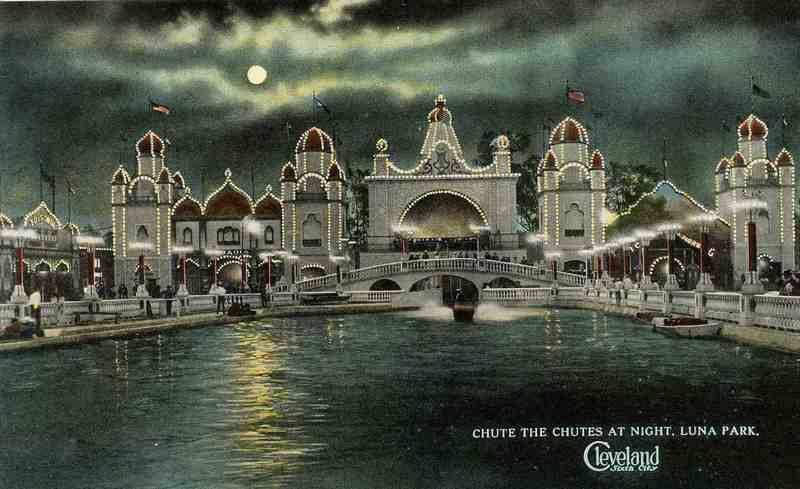

The Cleveland Carousel at the Luna Park amusement park that used to stand where Woodhill Homes now stands. [Sawyer and Bridget Baker]

When construction crews broke ground on Woodhill Homes exactly 80 years ago in June 1939, they first had to clear debris from demolished roller coasters, a crumbling race track and elaborate entrance gates decorated with crescent moons and gold spheres.

They were building on top of Luna Park, "Cleveland's Fairy Land of Pleasure." It was a amusement park at the end of the Woodhill trolley line, about a mile south of University Circle and shuttered in 1929.

A postcard of Luna Park at night. [Courtesy J. Mark Souther Postcard Collection, clevelandhistorical.org]

A postcard of Luna Park at night. [Courtesy J. Mark Souther Postcard Collection, clevelandhistorical.org]

The scene of workmen hauling away the fun to make room for something far more practical — housing — was a real sign of the times. By 1939, Cleveland and the nation had spent a decade trying to dig out from under the Great Depression. A lot of people couldn’t afford food or shelter, let alone rides on the merry-go-round.

Woodhill public housing in winter, 1939 [Cleveland Memory Project, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University]

Woodhill public housing in winter, 1939 [Cleveland Memory Project, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University]

That’s how Woodhill Homes and public housing in general began. It was a way to address a need. Public housing was one of the last New Deal programs of the 1930s, passed under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The idea was to build decent, affordable places to live for the country’s struggling families, with a focus in cities where the population was booming. Like Cleveland.

ideastream’s in-depth local reporting is made possible by donations from supporters like you.

Join us as a Member now.

ideastream.org/donate

A Fair Chance in the Pursuit of Happiness

Early aspirations for public housing were high and stayed that way for decades. "Throughout its neighborhoods and anywhere you look in Cleveland, the spirit of urban renewal is in the air," announces the 1962 documentary Cleveland: City on Schedule. It tells the story of public housing and urban renewal in Cleveland — and, as it was commissioned by the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce — in fawning terms.

Cleveland: City on Schedule (1962) documents urban renewal and public housing movements in Cleveland.

"Cleveland replaced hopelessness and degradation with decency, dignity and a fair chance in the pursuit of happiness," the documentary continues.

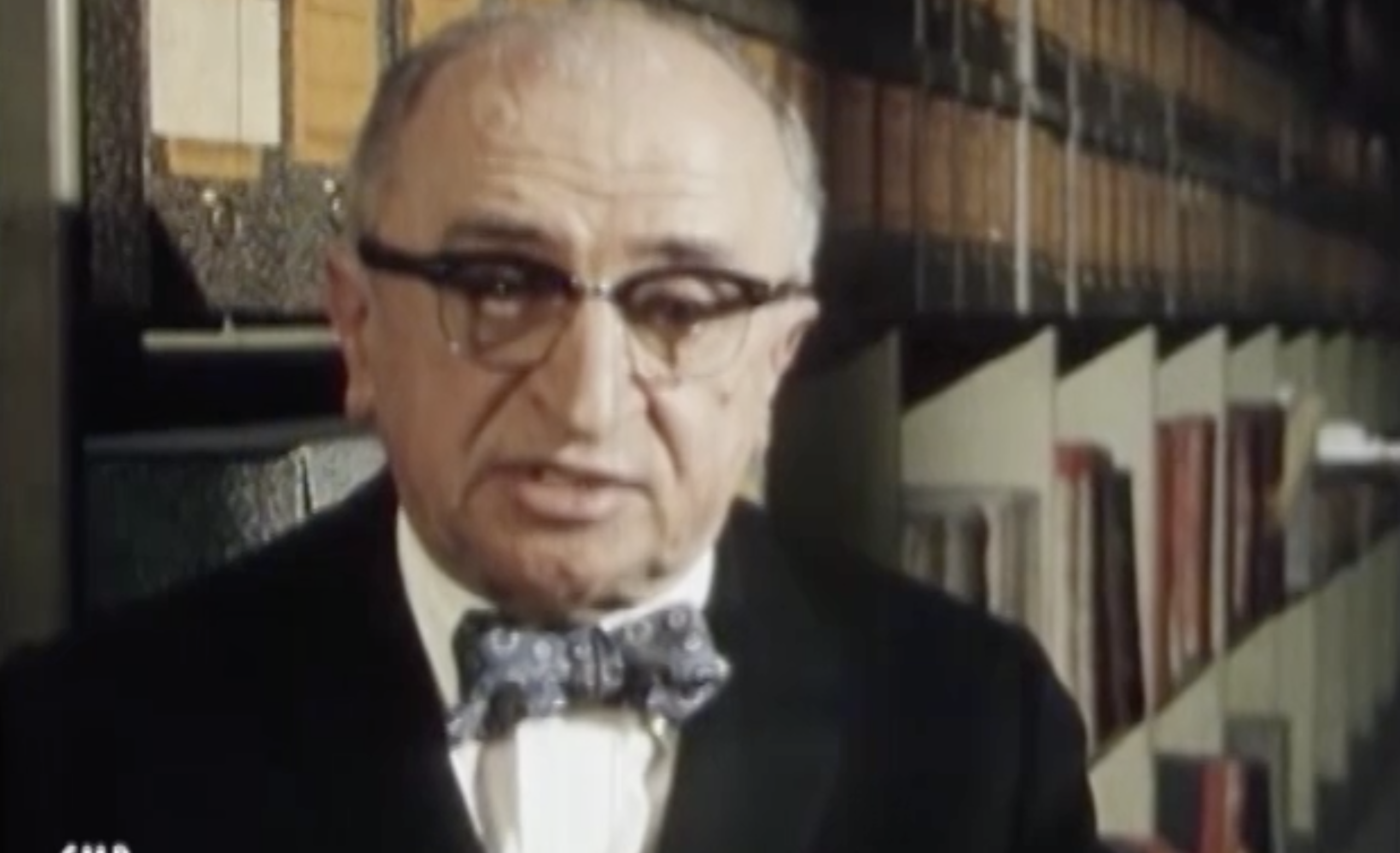

Cleveland was a leader in the movement to build public housing. The city had the first public housing authority in the country, thanks in part to a driven local lawmaker named Ernest Bohn.

Ernest Bohn was first elected to public office in 1929, as a Republican state representative. [From Cleveland: City on Schedule]

Ernest Bohn was first elected to public office in 1929, as a Republican state representative. [From Cleveland: City on Schedule]

Bohn believed public housing was the way to take care of Cleveland’s poor while also getting rid of the city’s slums.

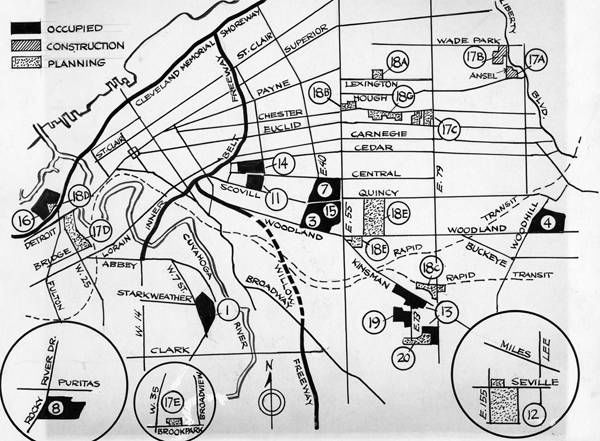

He eventually became the first director of what became the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA). During his tenure, Cleveland built some of the nation’s first public housing projects — including Woodhill Homes, which opened on Nov. 1, 1940.

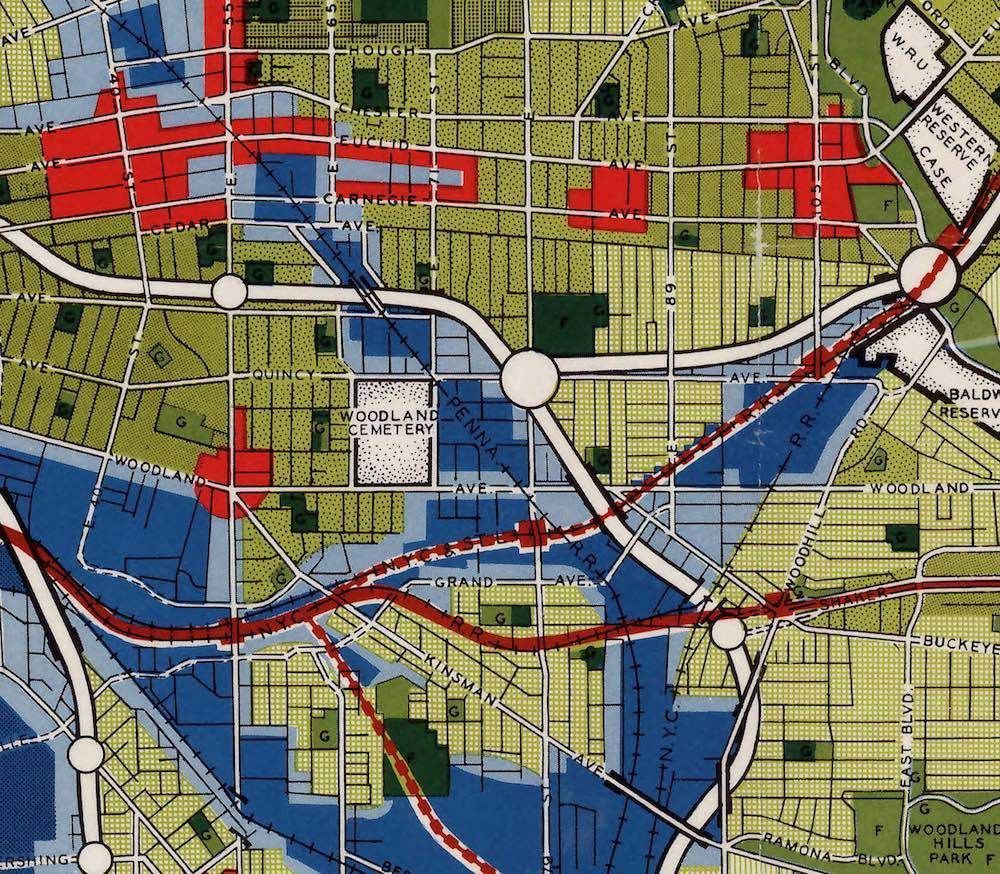

Some have accused Bohn of trying to confine the city’s poor to certain areas; others say he was passionate about providing decent housing for all. Whatever the case, he was effective. Today, CMHA manages more than 9,000 units of public housing, most of it built between the 1940s and 1960s. That’s 10 times as many units as Columbus and almost twice as many as Cincinnati.

A map from 1961 shows existing and planned public housing developments in Cleveland. Woodhill Homes is at the far right. [Cleveland Memory Project, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University]

A map from 1961 shows existing and planned public housing developments in Cleveland. Woodhill Homes is at the far right. [Cleveland Memory Project, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University]

For a long time, public housing was a welcome choice of Cleveland families of all races and ethnicities. What wasn’t to like about modern appliances, sturdy brick buildings and — all the rage at the time — linoleum floors?

Woodhill Homes had all of that, and more.

A poster promoting Woodhill Homes designed by artist Earl Schuler for the federal Works Progress Administration, November 1940. [U.S. Library of Congress]

A poster promoting Woodhill Homes designed by artist Earl Schuler for the federal Works Progress Administration, November 1940. [U.S. Library of Congress]

A Great Place to Live

Lou Latona lived in Woodhill Homes with his parents and four sisters between 1951 and 1967.

"This was a water fountain right here," he says, pointing to a cement-paved circle in front of the main entrance. "There were gardens over there."

He’s back on a warm spring day for a reunion with friends. As he walks the property, it seems like each stretch of sidewalk and stand of trees stirs a fond memory.

He gestures to some woods near a parking lot.

"We used to play chase in here. A bunch of us, 15 of us, running through the woods and hiding. It was great."

Life here was idyllic, he says. He still calls Woodhill “the projects,” and says he doesn’t think of that as a derogatory term.

"I was never embarrassed to tell anybody that I lived in the projects and nobody laughed and made fun of it," he says. "To me, it was where I lived and I loved it. It was just a great place to live."

He remembers when he lived here, the neighborhood was racially mixed, even if the boundaries were clear: The uphill half was mostly Italian-American families, like his, and the downhill half was mostly African American.

Most people were working class, he says, like his dad, who was a waiter. He loved visiting Woodhill's Community Center after school and playing for the neighborhood's interracial football team, the Vince Costellos, named for the former Cleveland Browns linebacker and Ohio native.

Lou Latona stands on the linoleum floor at his family's unit at Woodhill Homes, 1950s. [Courtesy Lou Latona]

Lou Latona stands on the linoleum floor at his family's unit at Woodhill Homes, 1950s. [Courtesy Lou Latona]

Lou Latona stands with two of his sisters at Woodhill Homes, 1960s. [Courtesy Lou Latona]

Lou Latona stands with two of his sisters at Woodhill Homes, 1960s. [Courtesy Lou Latona]

Lou Latona today, visiting his former unit at Woodhill Homes. [Gabriel Kramer / ideastream]

Lou Latona today, visiting his former unit at Woodhill Homes. [Gabriel Kramer / ideastream]

Change and a Backlog of Repairs

By the late 1960s, things changed. After World War II, dense townhouse neighborhoods like Woodhill Homes weren’t the fashion anymore. Houses with yards in the suburbs were. And if you were white, you could buy them — with federally backed mortgages that weren’t available to black families. Woodhill and most of Cleveland’s other public housing became predominantly African American.

A tour of Woodhill Homes' community gardens, planted as part of a horticulture program with Cleveland Public Schools, July 1965. [Cleveland Memory Project, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University]

A tour of Woodhill Homes' community gardens, planted as part of a horticulture program with Cleveland Public Schools, July 1965. [Cleveland Memory Project, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University]

Then, there were revisions to the original law establishing public housing. They included the 1969 Brooke Amendment, named after former U.S. Senator Edward Brooke (R-Mass.), the first African-American senator to be elected since Reconstruction.

"His idea was to make public housing available to the most needy people," says Mittie Jones, professor emerita of urban planning at Cleveland State University. She, too, grew up in public housing, in her hometown of Detroit, and worked for the Detroit Housing Commission before becoming a professor. She’s studied housing policy for most of her career.

Dr. Mittie Jones of Cleveland State University talks about her own experience growing up in public housing. [Gabriel Kramer / ideastream]

Dr. Mittie Jones of Cleveland State University talks about her own experience growing up in public housing. [Gabriel Kramer / ideastream]

She says before the Brooke Amendment, people paid closer to market rate rents for public housing. Afterward, the amount they paid was set at 25 percent of their income — regardless of the estimated cost to maintain the property or keep it financially viable, the way a commercial housing complex would.

The intention was that the federal government would step in to fill the gap. But Jones says that never happened. The lack of subsidy led to deferred maintenance, which in turn bred negative stereotypes.

"When people saw the exterior declining — the landscaping not being done, windows not being repaired, things like that — that probably contributed to some assumption being made that the people who were residing there were responsible for the decline," Jones says.

Fifty years later, deferred maintenance is still a big problem for public housing. The federal budget for repairs is now half what it was 20 years ago, and the Trump Administration wants to cut it again. That’s left a lot of housing authorities, including CMHA, struggling to keep up with a long backlog of repairs, and looking for private sources of funding.

Making The Homes Their Own

Even in the face of financial challenges, residents do their best to make Woodhill feel like home.

Neola Jones has lived at Woodhill Homes for 45 years — longer, she thinks, than any other current resident. She’s 92 now, and her walls are decorated with photos from her life and family portraits, including one of her son with some of his own poetry: When two people bring to love between them / binding as one / their souls interchange with each other's spirit as it come.

Neola Jones, right, with CMHA maintenance worker John Jackson. [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

Neola Jones, right, with CMHA maintenance worker John Jackson. [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

One of her favorite possessions, though, is outside. A white picket fence in her front garden.

"A lady that used to live here, she had to move and she gave it to me," Jones says.

The picket fence outside Neola Jones' unit is a Woodhill landmark. [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

The picket fence outside Neola Jones' unit is a Woodhill landmark. [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

She says she’s lucky because she’s friends with one of CMHA’s maintenance workers, John Jackson, who always comes on the double to fix her heat or repair the white picket fence in her front garden.

“She’s like a mother to me,” Jackson says.

Neola Jones nods and smiles. “When I call over to the office, I always say, ‘Will you send John?’”

Whatever happens physically with Woodhill in the future, she says the most important change in her eyes would be to make sure that every resident here feels that sense of care.

Eighty years after Woodhill was built, despite funding cuts and stereotypes, she says it’s time that people here once again have the resources and attention they need to thrive.

This story is part of a two-year reporting project about the past, present and future of Cleveland’s Woodhill Homes public housing development.