Making Art Work

Meet John Rivera-Resto

Editor's note: There has been ongoing conversation in Northeast Ohio about artist support in recent years, but little examination of how artists support themselves on a day-to-day basis. Through this series, ideastream highlights a sampling of area artists and the various ways they make their finances work.

John Rivera-Resto is a Clevelander with roots in Puerto Rico, and he lives an artist’s life he never intended.

Puerto Rico - hoy ayer y para siempre (today, yesterday and forever) 1976 [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Puerto Rico - hoy ayer y para siempre (today, yesterday and forever) 1976 [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

He’s a painter, writer, designer, actor and director, and he never knows where his next buck is coming from. But, life has taught him that the phone will soon ring with a new job.

ideastream’s in-depth local reporting is made possible by donations from supporters like you.

Join us as a Member now.

ideastream.org/donate

Capturing Culture in Paint

“The minute you make a painting and you give it to your friend - that’s art. The minute the friend gives you five cents - that’s business.”

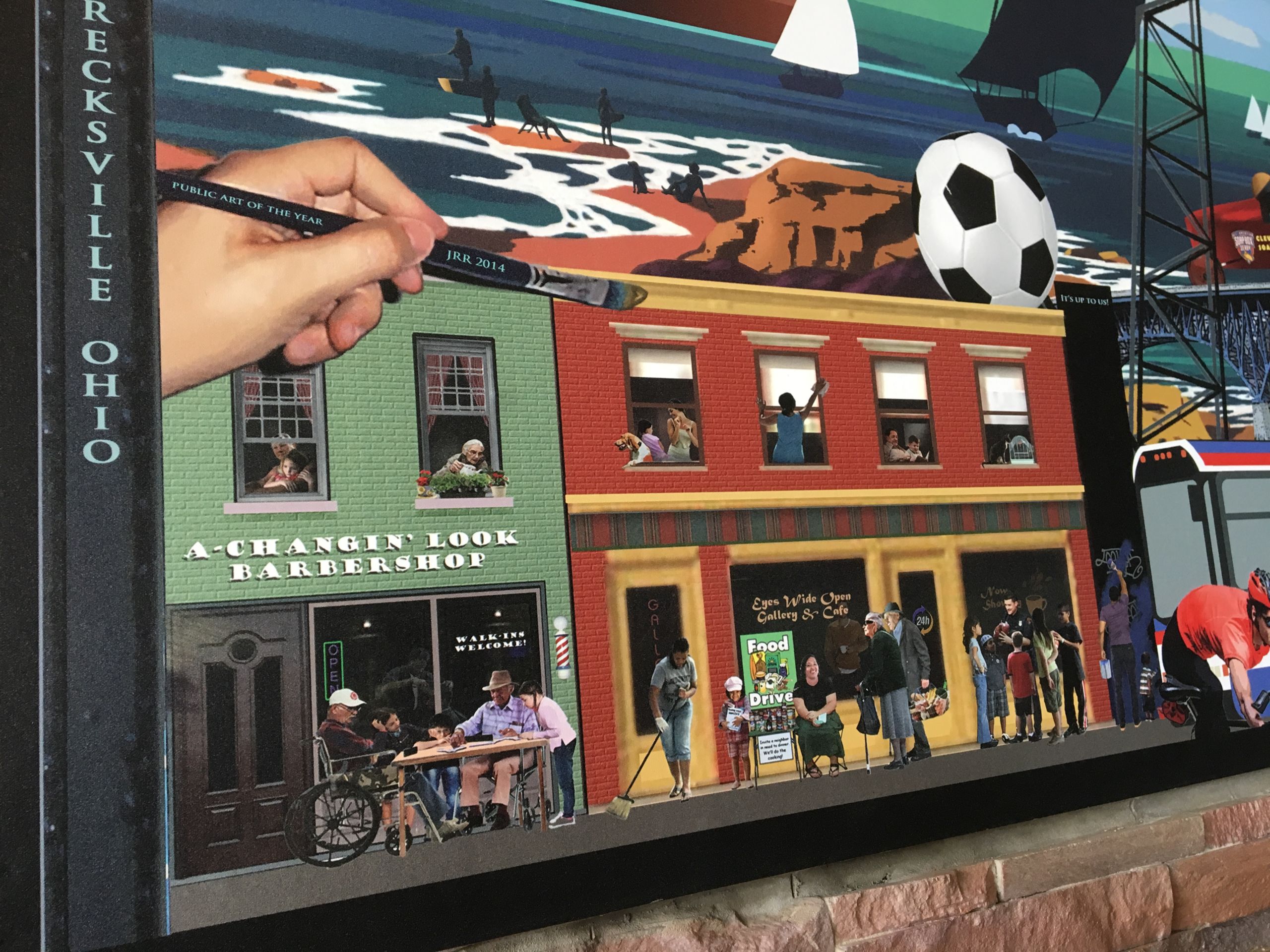

One Fall morning, John Rivera-Resto gazed at his huge mural at the corner of West 25th and Clark Avenue with a mixture of pride and sadness. Two stories high and over 100 feet long, the painting depicts the local community as it has changed over the years. It was an immediate hit when it was unveiled in 2014.

“I knew I was going to get a reaction, but I didn’t know it was going to be embraced to this level,” he said.

The community loved this representation of their lives, and people were outraged when someone defaced it, two years ago.

The 60-year-old artist has done numerous life-sized, photo-realistic paintings, in many spots around town. But this was one of his favorites, because of the uplifting social commentary.

“Everybody got it,” said Rivera-Resto. “They said, ‘Yeah, this is where we want to go.’ I interviewed a lot of people, and I put their stories on the wall.”

The vandalism would prove to only be a temporary setback for an artist who has made a career of putting stories on walls...

You can see his work in restaurants, sports bars and travel agencies and on the sides of buildings throughout the city.

Over the course of four decades, the artist has learned not to have any illusions about what it takes to keep food on the table.

Rivera-Resto in his studio, circa late 1990s [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Rivera-Resto in his studio, circa late 1990s [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

“I have no ingrained philosophy that says: ‘Oh, this is fine art. I'm not gonna degrade myself by doing commercial art.’ The minute you make a painting and you give it to your friend - that’s art. The minute the friend gives you five cents - that’s business.”

Rivera-Resto's collection of celebrities for the walls of Thinkers Coffeehouse in Playhouse Square, circa 1990s [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Rivera-Resto's collection of celebrities for the walls of Thinkers Coffeehouse in Playhouse Square, circa 1990s [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Rivera-Resto began developing his artistic and business smarts as a boy in Las Piedras, Puerto Rico. But, it’s not like an art career was any kind of goal.

The Reluctant Artist

“I never wanted to become an artist, ever,” he said. “The smell of paint made me throw up.”

A devoted fan of classic Hollywood movies, he longed for the life of his swashbuckling idol, Errol Flynn.

"I wanted to be an adventurer," he said. "That was my goal."

And he loved to read. Many of the books he consumed had to do with the worlds of art and culture.

“I've always been voraciously curious,” he said. “I was always fascinated by artists like DaVinci and Michaelangelo and their times.

My gripe with life is this: I'm not going to live long enough to learn all those things I want to learn. Part of it was wondering how he did the Sistine Chapel, and so I read about it.”

Images transfixed him as well. For instance, the head of a pig with an apple in its mouth at a market stayed with him for days, and he was compelled to try to duplicate it on paper. The more he practiced the better he got. Such sketches led to his first professional commission.

The vista of his childhood back at Las Piedras, Puerto Rico [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

The vista of his childhood back at Las Piedras, Puerto Rico [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

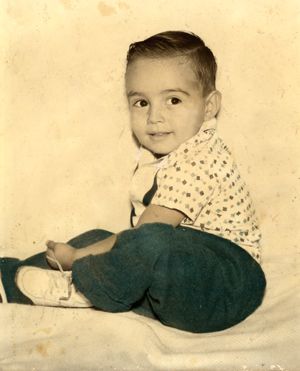

The pastor of a prominent Pentecostal church saw some of 16-year-old Rivera-Resto's work and hired him to do a mural on the front of a new temple that the church was building. The young artist did him one better.

Rivera-Resto's first mural, El Jardin del Eden (The Garden of Eden), was painted for the altar at Iglesia Fuente de Salvación Misionera Inc. located in el bario Lijas de Las Piedras, Puerto Rico [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Rivera-Resto's first mural, El Jardin del Eden (The Garden of Eden), was painted for the altar at Iglesia Fuente de Salvación Misionera Inc. located in el bario Lijas de Las Piedras, Puerto Rico [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Over the course of six months, he painted a 2,275-square-foot rendering of the Garden of Eden around the altar. Rivera-Resto says this monumental work caused quite a buzz on the island, leading to over two dozen more mural commissions. He says it was his personal art school.

“At 17, I was making more money painting murals than my father who was a plant manager at a factory, where they made hospital and office equipment,” he said. “Everybody paid me cash. I never saw the money. My father collected it and put it in a savings account in my name.”

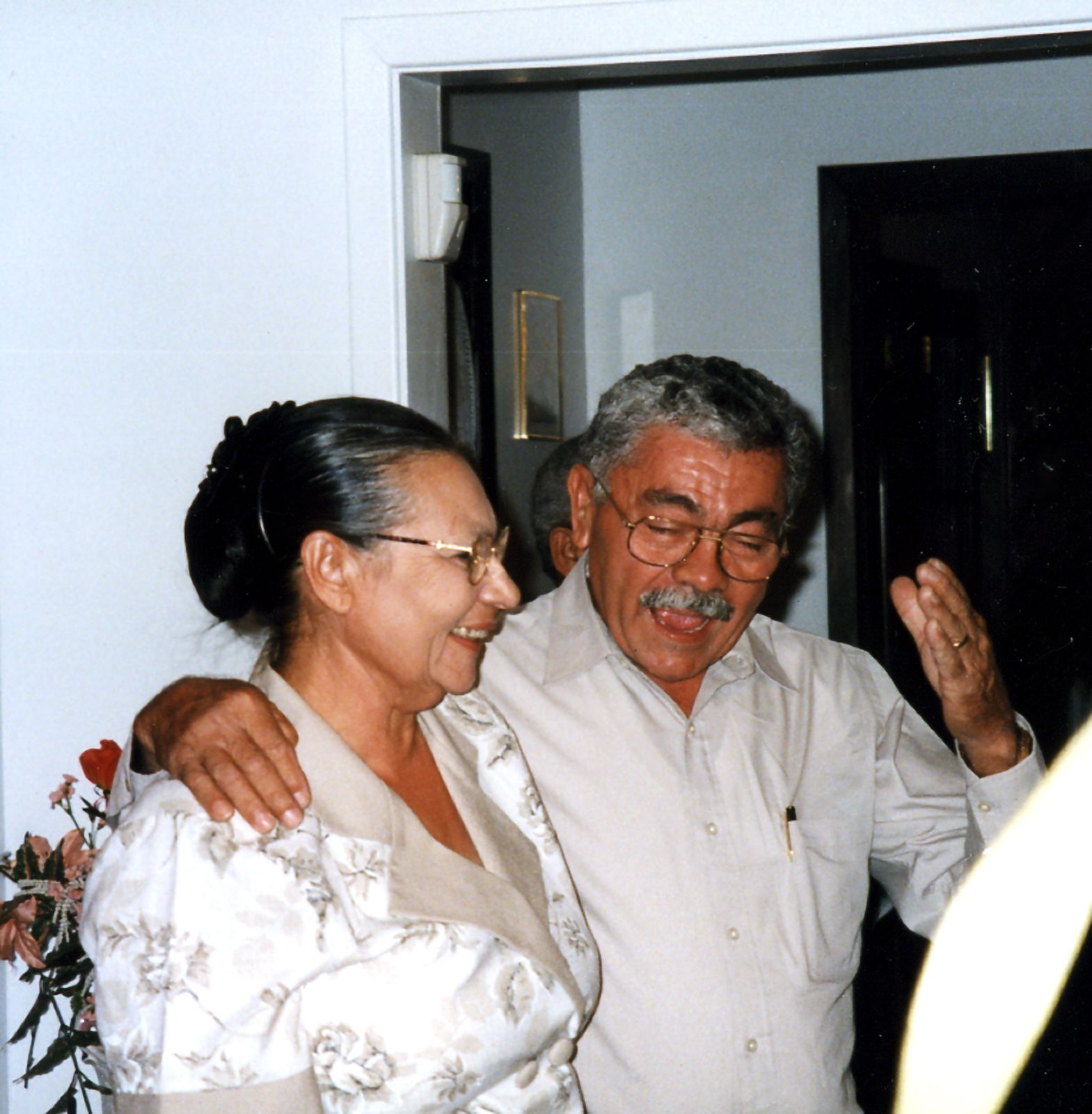

Rivera-Resto's parents, Jesua Resto-Placeres de Rivera and John Rivera [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Rivera-Resto's parents, Jesua Resto-Placeres de Rivera and John Rivera [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

He says he also started acting in local theater productions as a way to escape a shy personality.

“I loved the acting because that's one way to be Errol Flynn,” he said. “Nobody dies on stage. You're the hero. And because Errol is a fencer, I took fencing.”

Rivera-Resto emulates his childhood hero Errol Flynn [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

Rivera-Resto emulates his childhood hero Errol Flynn [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

Coming to Cleveland

“I didn't want to know about aesthetics. I didn't want to know how I felt about something. Tell me what color to mix with which color. I'll handle the rest.”

Being on stage was a step towards the glamorous life he’d always dreamed of, but a Cleveland relative had a different idea. Without telling him, great-uncle Esau submitted some of the boy’s work to an art school here, and he was quickly accepted as a student. But, the young artist found he wasn’t suited to the rigors of formal education. The teachers bored him and he was paying for school with a part-time job as a welder at night, which didn’t help his attention span.

One of Rivera-Resto's recent projects was an astronomical mural for the dome of the Cuyahoga County Juvenile Justice Center [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

One of Rivera-Resto's recent projects was an astronomical mural for the dome of the Cuyahoga County Juvenile Justice Center [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

“I hated every minute of it,” he said. “I didn't want to know about aesthetics. I didn't want to know how I felt about something. Tell me what color to mix with which color. I'll handle the rest.”

That sort of pragmatic attitude stood him in good stead as he went looking for painting jobs. His brother came to Cleveland and the two of them lived together to save money.

Rivera-Resto lived with his brother Ricky in the early Cleveland days, and they have remained partners in a number of art projects [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Rivera-Resto lived with his brother Ricky in the early Cleveland days, and they have remained partners in a number of art projects [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

“I don't drink, I don't smoke, I'm very frugal, don't do drugs,” he said. “This is when Cleveland was at the worst – in the early 80s, middle 80s – and jobs were hard to come by, but I was always getting them, and I thought I was doing okay.

[courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

[courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

He painted signs. He did murals. He even did some Spanish tutoring to make ends meet. But it wasn’t enough. He started losing faith that he could survive on painting. So, he took a job as a program director at the Boys and Girls Club, and he even did a stint as a Burger King manager to help pay for a degree in art education at Cleveland State University.

He figured if he couldn’t make a living as an artist, then he could teach others what he had learned in the real world.

“I'll be one of the few people who can actually say I've been there,” he said. “And I can do it in Spanish and English, and I'm very theatrical when I teach my class. It's a performance.”

Rivera-Resto instructs his crew from atop the scaffolding [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Rivera-Resto instructs his crew from atop the scaffolding [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Rivera-Resto says he limits his teaching gigs to one-time lectures and presentations, due to the preparation time he needs. He’s spoken at Kent State University, the Cleveland Institute of Art, Cuyahoga Community College and some Cleveland Public Schools.

![Indians catcher Sandy Alomar eyes peer out of his mask with a combination of concern and determination [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]](./assets/O9OqaHnq5a/sandy-alomar-painting-by-john-rivera-resto-1994-1200x800.png)

Indians catcher Sandy Alomar [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Indians catcher Sandy Alomar [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

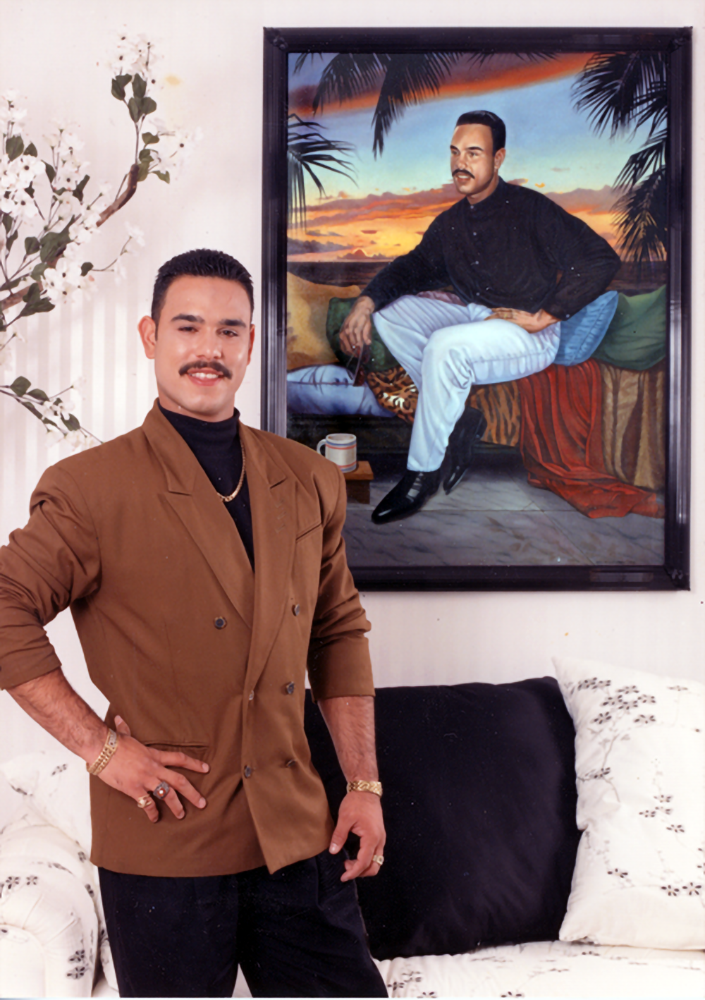

His performance talents proved to be useful in selling himself as an artist and designer to the occasional corporate client, and his Spanish language skills came in handy, as well. In the 1990s, Rivera-Resto did some consulting work with the Cleveland Indians to help acculturate some young Latino players to their new city. For instance, he designed popular slugger Carlos Baerga’s house from the furniture to the silverware.

Carlos Baerga poses by his Rivera-Resto portrait [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

Carlos Baerga poses by his Rivera-Resto portrait [courtesy: John Rivera-Resto]

The Hustle Never Ends

“A typical day means I try to go to bed at 4:00 in the morning, because I need to go to bed. And then, I'm angry because I had to go to bed and couldn’t stay up doing something else.”

Rivera-Resto juggles between one to five projects at a time. He estimates 75% of his income, these days, comes from restaurant and nightclub design, which includes a mural in many cases. A good portion of the remaining 25% comes from private commissions.

And his old Errol Flynn itch is being scratched by working with Cleveland’s LatinUs Theater Company – a troupe that performs plays in Spanish with English subtitles

“In theater, you make no money, period,” he said. “You do it because you love it. You make maybe your expenses, but not necessarily make a living.”

It’s just another activity to fit into his busy schedule.

“A typical day means I try to go to bed at 4:00 in the morning, because I need to go to bed,” he said. “And then, I'm angry because I had to go to bed and couldn’t stay up doing something else.”

“’Honey, I am your slave on Saturday. Anything you need to do, anything you want to do, I'm with you,’” he said. “She's a girl from Jersey who keeps reminding me: ‘We bury people in walls in Jersey. Just keep that in mind.’”

Those early morning hours are generally filled with reading everything from a classic Hispanic author to a dish-washing manual to Steven Hawking. And if he’s particularly vexed by a design problem, he’ll often turn to video games as a distraction.

Charlie helps Rivera-Resto navigate a video game [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

Charlie helps Rivera-Resto navigate a video game [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

By contrast, his wife of ten years, Nancy, is a morning person who acts as the family bookkeeper. In return, he turns his focus to her every weekend.

John and his Jersey Girl Nancy [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

John and his Jersey Girl Nancy [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

“’Honey, I am your slave on Saturday. Anything you need to do anything you want to do, I'm with you,’” he said. “She's a girl from Jersey who keeps reminding me: ‘We bury people in walls in Jersey. Just keep that in mind.’”

Looking to the Future

“Everything I learned in life, from painting murals to the treatises of DaVinci to marketing, plays into it. The background that you have is just as important as art.”

Rivera-Resto never had any kind of health insurance coverage until he married Nancy in 2009 and was added to her policy. Up until recently, medical expenses and retirement have been dealt with through a combination of savings, investments and a frugal lifestyle.

“I don't owe anything,” he said. “No cars, no credit cards, no nothing. Or I go to the dentist, I'm gonna pay cash. ‘Let's negotiate.’”

He had significant medical bills in recent years, including a cancer operation, a disc replacement and double hernias. His nose was cracked twice and he said he never fixed it.

“If I go by the genes in my family, at 65 I turn gray and I'll live to be 100. Unless I get killed, and since I'm being a very good boy, I don't think that's going to happen,” he said. “So probably, it's gonna be a banana peel that gets me.”

Actually, there was one piece of personal damage that was recently repaired.

Workers spray down Rivera-Resto's "It's Up to Us" mural as a part of its restoration [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

Workers spray down Rivera-Resto's "It's Up to Us" mural as a part of its restoration [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

A crowd-funding campaign, along with a paint donation from Sherwin-Williams, led a reluctant Rivera-Resto back to the defaced mural on Clark Avenue. The artist says he generally prefers to look forward and doesn’t return to old work.

“That was an agony, because I didn't want to go back,” he said. “Doing it was, I don't know, it's like being drafted into the army. That's what it felt like. I didn't want to come back. But, I keep getting calls, emails, and I realized, I guess this means a lot of things to a lot of people.”

Rivera-Resto says the mural restoration allowed him to do some detailing he didn't have time to do the first time around [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

Rivera-Resto says the mural restoration allowed him to do some detailing he didn't have time to do the first time around [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

On the far right side of the mural, a man and a young boy are depicted with their backs to us. Both are wielding brushes, covering up some streaks of graffiti with a new coat of blue paint. It’s an appropriate coda to the story of an artist who has pushed back when life threw challenges at him.

Ironically, Rivera-Resto included a scene of a man and a young boy painting over graffiti scrawls in the original painting [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

Ironically, Rivera-Resto included a scene of a man and a young boy painting over graffiti scrawls in the original painting [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

“Everything I learned in life, from painting murals to the treatises of DaVinci to marketing, plays into it,” he said. The background that you have is just as important as art. Art is nothing more than an extension of your finger to the rest of your being.”

"Genesis Hands" [image: shutterstock.com]

"Genesis Hands" [image: shutterstock.com]