The Rise of

Rural Suicides

IN OHIO

Diseases Of Despair, Deficits Of Hope

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series focused on the increasing rate of suicides across Ohio. In it, we explore why rural areas have seen more deaths by suicide, how older adults are particularly vulnerable, and how groups are figuring out how to better tailor their services to those who need help.

If you or someone you know needs help call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK.

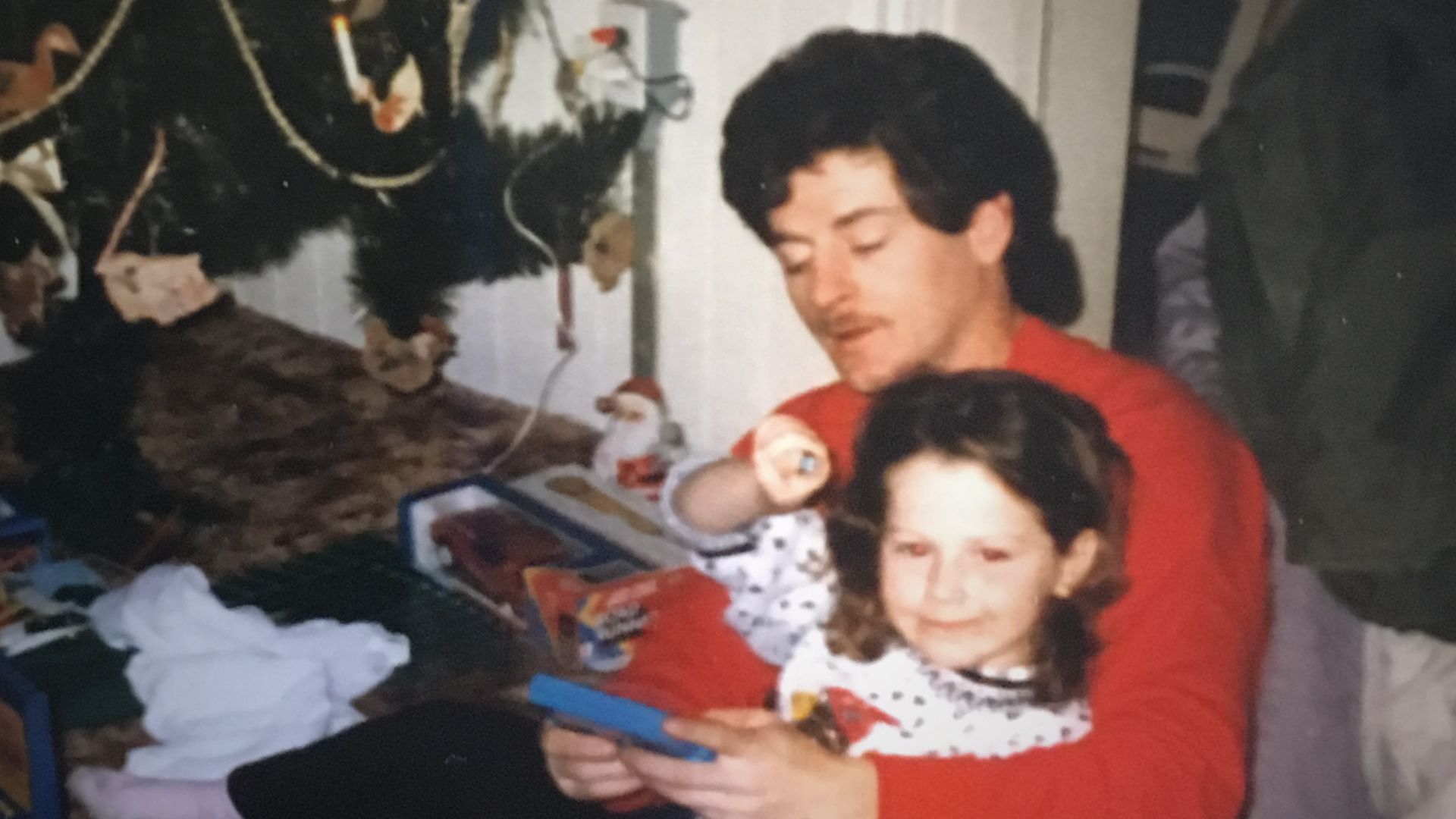

"He was a really athletic, funny, goofy guy — that’s just who my dad was. He had finally bought a house. He worked at the factory, lost his job and then had a hard time picking himself back up,” said Ashtabula resident Dia Fleming, about her father.

Fleming’s father Ronald, who struggled with addiction, killed himself in the garage of their family home in 2006.

Former Ashtabula resident Ronald Fleming [Dia Fleming]

Former Ashtabula resident Ronald Fleming [Dia Fleming]

Fleming, who was a teenager at the time, said her father once dreamed of being a professional boxer, but life caught up with him after the rubber factory where he worked in Geneva shut down.

“When you don’t feel like you have a future — and you are not used to that — is when things get real scary and real dicey,” she said.

Fleming, who now works as a professional counselor, explains that her father simply lost hope.

Death by suicide, like the one experienced by the Fleming family, is becoming more common in Ohio. Suicide deaths increased 45 percent from 2007 to 2018, according to a recent report from the Ohio Department of Health.

Nationally, suicide is one of the leading causes of death, and in Ohio in 2018, it was the 11th leading cause of death among all ages. Men between 55 and 64 years old had the highest number of suicide deaths, according to the report. And the suicide rate for men was nearly four times higher than the suicide rate for women.

Over the 11-year period examined in the report, suicide rates were highest in rural Appalachian counties, many along Ohio’s southern border. Meigs county, on Ohio's southeastern border with West Virginia, had the highest suicide rate in the state.

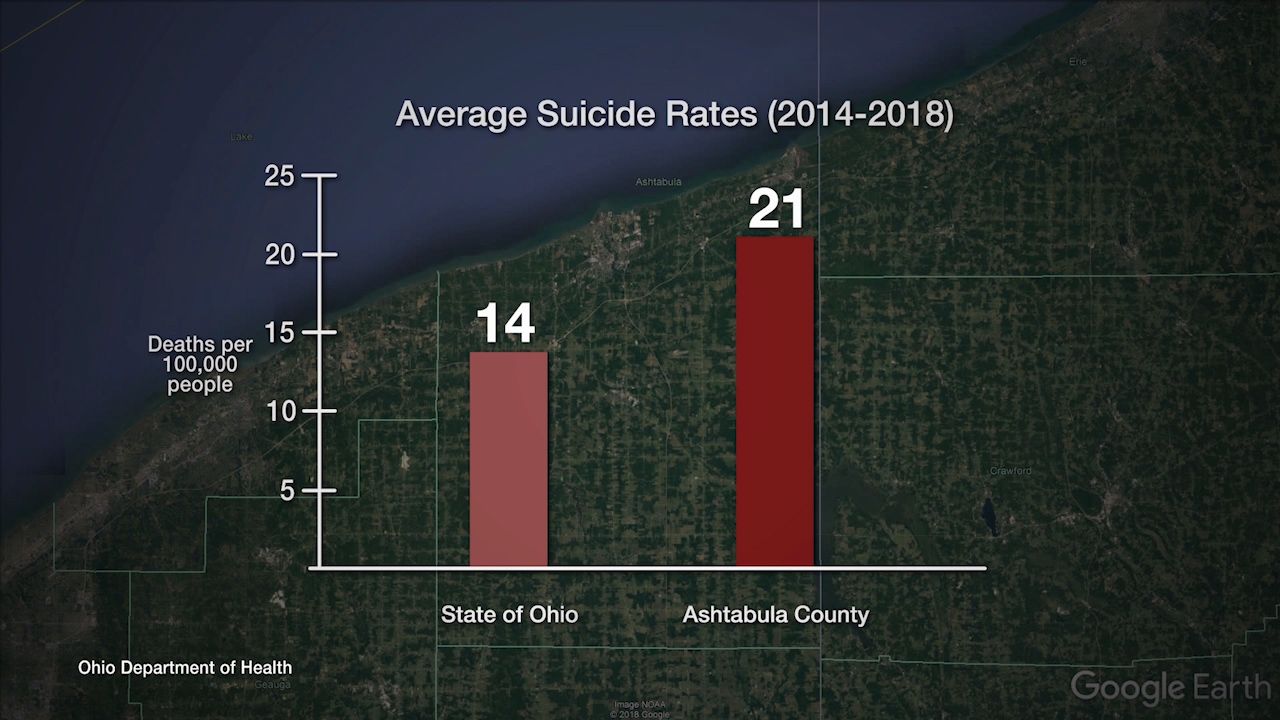

Ashtabula, an Appalachian county in northeast Ohio, had the third highest rate of suicide in Ohio, according to the Ohio Department of Health report.

Sparsely populated, Ashtabula County doesn’t have the highest number of suicide deaths, but the rate of people who die by suicide here is much higher than in some larger Ohio communities.

ideastream's in-depth local reporting is made possible by donations from supporters like you.

Join us as a Member now.

ideastream.org/donate

Ashtabula city

Harbor area

Matt Butler, who heads the local response team that reaches out to families after tragic losses, says Ashtabula County has a split personality.

The restaurants and trendy stores in the city of Ashtabula, on Bridge Street near the harbor, are a sign the city is rebounding from the economic decline of the 80's and 90's, when many factories closed.

The entire county is pivoting to tourism and other service jobs, but high rates of generational poverty persist, said Butler who is also a supervisor at a community counseling center. Ashtabula's unemployment rate also remains higher than the overall state number and incomes are lower as well.

Ashtabula is in a state of crisis because so many people are lost every year to both suicides and drug overdoses, said Butler. There is a confluence of economic instability and drug use which is driving suicide rates higher, Butler said.

“There are many, many positives about Ashtabula County, but for a certain subset of folks, something is gone that really isn’t going to be regained,” he said.

The average suicide rate between 2014 and 2018 in Ashtabula was 21 per 100,000 people — which is much higher than the statewide average rate of 14 per 100,000, according to the ODH report.

“People are dying what I would consider to be diseases of despair, caused by a deficit of hope," Butler said.

A recently released report, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), also pointed to these 'diseases of despair' as a driving force behind lower life expectancy rates in U.S., particularly in Ohio and other states in the Ohio Valley.

White men, as a demographic group, are particularly at risk of suicide. According to the Ohio Alliance for Innovation in Population Health May 2019 report, suicide rates are up across all demographic groups in Ohio, but white men are the most likely to die at their own hand.

Fleming says her father, Ronald, fit this demographic trend and was in many ways trapped by a culture which does not encourage men to seek help for mental health issues.

Social isolation and fear of being perceived as weak kept her father from seeking help, Fleming said.

“Part of it is not talking about things a lot, keeping that stigma in the air where it’s not OK for an older white male to say, ‘I need help, I’m not OK,’” she said.

Ashtabula county is pivoting to tourism and other service jobs, but high rates of generational poverty persist. [Mary Fecteau / ideastream]

Ashtabula county is pivoting to tourism and other service jobs, but high rates of generational poverty persist. [Mary Fecteau / ideastream]

Abandoned factory in the city of Ashtabula [Mary Fecteau / ideastream]

Abandoned factory in the city of Ashtabula [Mary Fecteau / ideastream]

Seeking Help from a "Suicidologist"

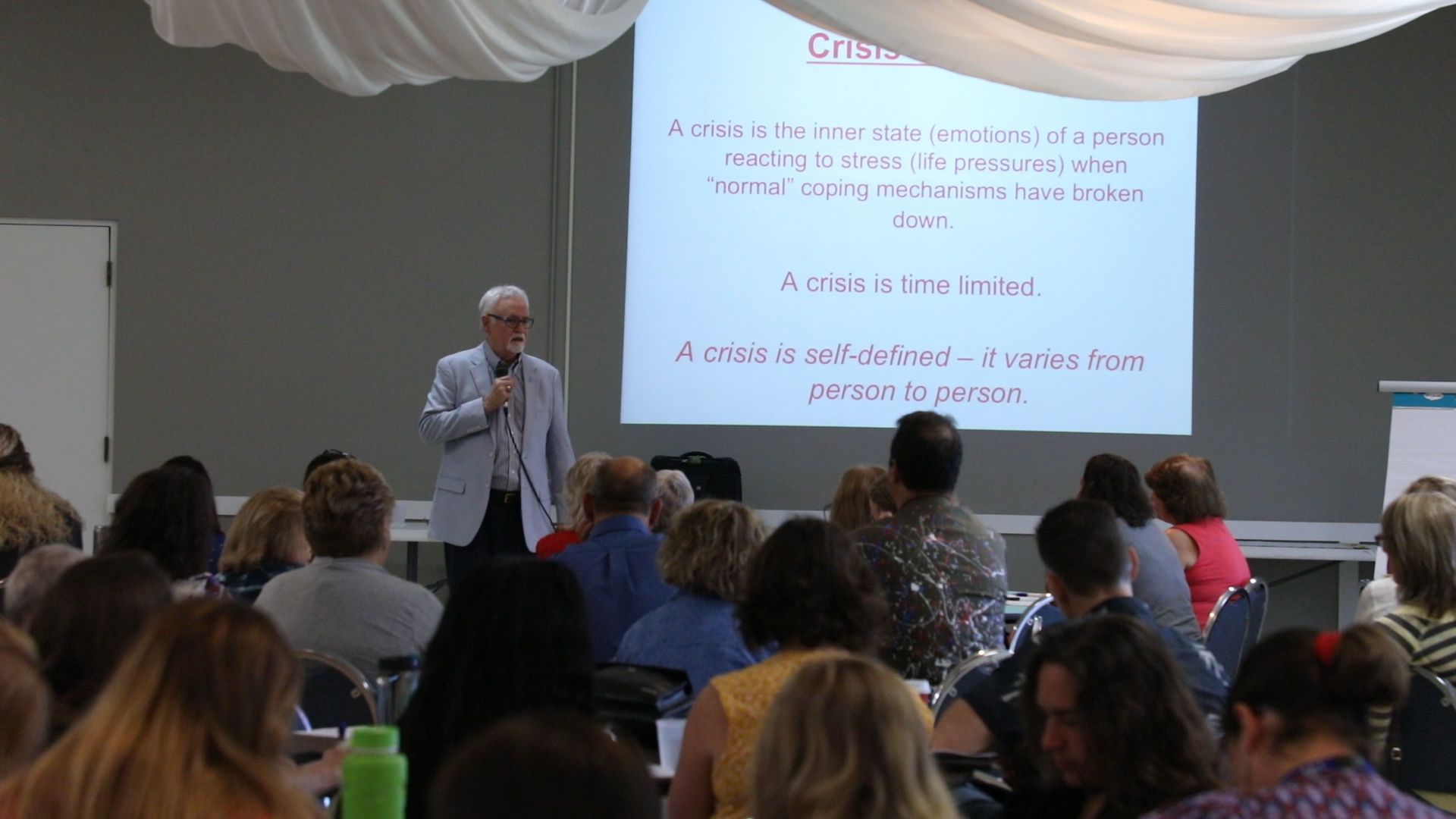

Rural communities, like Ashtabula County, also have the added problem of physical isolation, said Frank Campbell, a national suicide expert who was invited by Ashtabula health officials to share his insights on combating high rates of death.

“Quite often people with thoughts of suicide tend to isolate and withdraw. If you already live in a very isolated county, it might be miles before the next person. [It might be] once a week where you might have friend drop by. So it's very difficult to maintain that sense of community when you're so isolated from the resources,” said Campbell, who is based in Louisiana.

Campbell, who calls himself a suicidologist, spoke at the Elks Lodge to a room full of health professionals, counselors and suicide survivors.

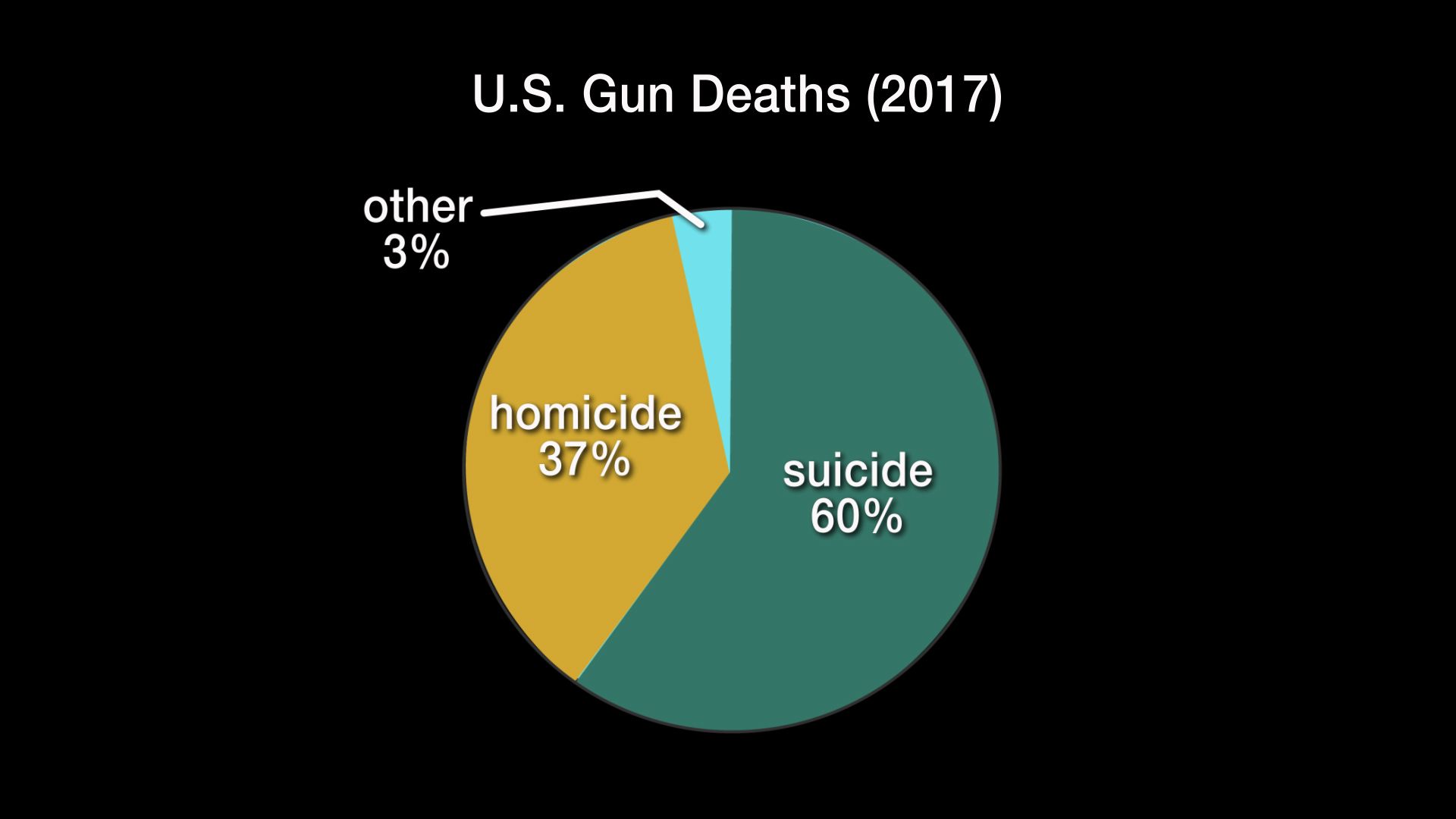

One suicide occurs every 11 minutes in the U.S., and more people die from suicide than homicides, Campbell told the audience.

Campbell also spoke about the methods most commonly used to complete suicides. “More than half were committed with firearms,” he said.

People often want to ignore this fact, he said, but firearms are a particularly lethal method.

“Firearms have a low reversibility. So if you shoot yourself it's much more likely you will die as a result of that action. But if you take an overdose you'd have time to change your mind and call for help," he said.

Suicides account for some 60 percent of gun deaths in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“People say, 'if I take the guns away they’ll just do something else.’ What we know is people tend to stick to a plan, so if you remove that object they say they will use, there’s a good chance we will have more opportunity to help them stay alive,” said Campbell.

Don’t be afraid to ask someone if they are thinking of taking their life, he said. Some people think about it but never try to complete the act.

“Some people attempt it and then have a buoyancy about life and never attempt again,” Campbell said.

It’s about the individual conversation and finding out what is going on with that person, he said.

Suicidologist Frank Campbell says suicide and suicide attempts are different for every individual. Campbell says it difficult to generalize the cause or the solutions.

Suicidologist Frank Campbell says suicide and suicide attempts are different for every individual. Campbell says it difficult to generalize the cause or the solutions.

Suicidologist Frank Campbell speaks at the Elks Lodge in Ashtabula to people concerned about rising suicide rates in the county. [Mary Fecteau / ideastream]

Suicidologist Frank Campbell speaks at the Elks Lodge in Ashtabula to people concerned about rising suicide rates in the county. [Mary Fecteau / ideastream]

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Rebuilding After

Loss

Ashtabula residents Catherine Focht-Phipps (left) and Pauline Jensen are sisters who both died by suicide just a few years apart. [Cheryl Throop]

Ashtabula residents Catherine Focht-Phipps (left) and Pauline Jensen are sisters who both died by suicide just a few years apart. [Cheryl Throop]

Ashtabula County resident Cheryl Throop wishes she could go back and have deeper conversations with her two daughters, who both died by suicide.

Pauline Jenson, who suffered from anxiety, died in 2011 at the age of 41. Then five years later, Throop's daughter Cathy Focht-Phipps took her life when she was 43 years old.

Throop talked about how Pauline attempted to take her life before, but the family thought she had moved past thoughts of suicide.

Ashtabula resident Cheryl Throop was devastated by the loss of two daughters by suicide, but initially resisted seeking help with her grief because of the stigma around suicide.

Ashtabula resident Cheryl Throop was devastated by the loss of two daughters by suicide, but initially resisted seeking help with her grief because of the stigma around suicide.

Throop's other daughter, Cathy, was outgoing and was often the life of the party, but she had a history of drug addiction and fell into depression because of problems in her marriage, said her mother.

A week before Cathy took her life there were signs that, in retrospect, Throop thinks she may have missed. She described one scene in specific that sticks with her to today.

“She was doing some weeding for me and she just seemed so sad. I asked her and she said, ‘I’m alright I’m just having a bum day.’ I should have just sat and talked to her [but] I went back in the house.”

Although she wishes she could turn back time, Throop says she knows that is not possible. She struggled for many years trying to understand why this happened to her daughters and what she could have done differently.

After her daughters' deaths, Throop said she felt isolated in her grief. Many of her friends didn't quite know what to say and there was an awkwardness to their conversations, she said.

"Nobody mentions the name anymore. It's like they didn't live. It's like you didn't have that child. They just don't say anything. Everybody backs off from you."

Initially Throop resisted seeking help with her grief because of the stigma around suicide.

“One time this woman said, ‘I didn't realize you lost a daughter,’ and then she asked how and I didn’t know what to say. Then I said suicide, but not a normal suicide. What is a normal suicide? In my mind I didn't want anyone to think badly of her,” Throop said.

Throop says now she knows better. She has also found help to cope with grief through a local support group, at the Heart Beat Community Counseling Center.

“And I was deep in my sorrow so I kept pushing them off, but they kept calling me. Maybe it was about six months or longer. And it was the best thing I ever did,” she said.

She tried traditional counseling but that didn't work for her. At the counseling center Throop meets regularly with a loss group and this is helping her cope, she said.

"There are moments you cry. And then there are moments you can help some other person get through it. That's what it's about," Throop said.

Ashtabula needs more programs like Heart Beat, she said.

Suicidologist Frank Campbell agrees. Rural communities like Ashtabula need more resources to help survivors of loss and to intervene with people who have alcohol, drug and gambling dependencies.

Cheryl Throop listens as suicidologist Frank Campbell talks about strategies to help people considering suicide. [Mary Fecteau / ideastream]

Cheryl Throop listens as suicidologist Frank Campbell talks about strategies to help people considering suicide. [Mary Fecteau / ideastream]

Campbell is a huge advocate of better training for the medical community on how to help people who are considering suicide. Too often people who are taken to a hospital with thoughts of suicide are not immediately connected to mental health services, he said.

"Over 10 million people every year think about suicide. Forty seven thousand die by suicide. That's an enormous gap. And we can help them put a rail around that Grand Canyon called suicide," he said.

In addition to better training for professionals, and more counseling for survivors, rural areas also need to regain something that used to be a hallmark in small communities. Campbell explains that a sense of connectedness has been lost in rural communities.

Rebuilding that community connectedness would be Campbell's number one prescription for preventing suicides.